- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Ethnic differences in prediabetes incidence among immigrants to Canada: a population-based cohort study

Read this article at

Abstract

Background

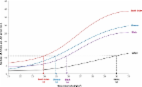

Prediabetes appears to be increasing worldwide. This study examined the incidence of prediabetes among immigrants to Canada of different ethnic origins and the age at which ethnic differences emerged.

Methods

We assembled a cohort of Ontario adults (≥ 20 years) with normoglycemia based on glucose testing performed between 2002 and 2011 through a single commercial laboratory database ( N = 1,772,180). Immigration data were used to assign ethnicity based on country of origin, mother tongue, and surname. Individuals were followed until December 2013 for the development of prediabetes, defined using either the World Health Organization/Diabetes Canada (WHO/DC) or American Diabetes Association (ADA) thresholds. Multivariate competing risk regression models were derived to examine the effect of ethnicity and immigration status on prediabetes incidence.

Results

After a median follow-up of 8.0 years, 337,608 individuals developed prediabetes. Using definitions based on WHO/DC, the adjusted cumulative incidence of prediabetes was 40% (HR 1.40, CI 1.38–1.41) higher for immigrants relative to long-term Canadian residents (21.2% vs 16.0%, p < 0.001) and nearly twofold higher among South Asian than Western European immigrants (23.6%; HR 1.95, CI1.87–2.03 vs 13.1%; referent). Cumulative incidence rates based on ADA thresholds were considerably higher (47.1% and 32.3% among South Asians and Western Europeans, respectively). Ethnic differences emerged at young ages. South Asians aged 20–34 years had a similar prediabetes incidence as Europeans who were 15 years older (35–49 years), regardless of which prediabetes definition was used (WHO/DC 14.4% vs 15.7%; ADA 38.0% vs 33.0%).

Related collections

Most cited references20

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Deriving Ethnic-Specific BMI Cutoff Points for Assessing Diabetes Risk

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Lifetime risk of developing impaired glucose metabolism and eventual progression from prediabetes to type 2 diabetes: a prospective cohort study.

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found