- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Progress Toward Polio Eradication — Worldwide, January 2019–June 2021

research-article

John Paul Bigouette , PhD

1

,

2

,

,

Amanda L. Wilkinson , PhD

2 ,

Graham Tallis , MPH

3 ,

Cara C. Burns , PhD

4 ,

Steven G. F. Wassilak , MD

2 ,

John F. Vertefeuille , PhD

2

27 August 2021

Read this article at

There is no author summary for this article yet. Authors can add summaries to their articles on ScienceOpen to make them more accessible to a non-specialist audience.

Abstract

In 1988, when the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) began, polio paralyzed

>350,000 children across 125 countries. Today, only one of three wild poliovirus serotypes,

type 1 (WPV1), remains in circulation in only two countries, Afghanistan and Pakistan.

This report summarizes progress toward global polio eradication during January 1,

2019–June 30, 2021 and updates previous reports (

1

,

2

). In 2020, 140 cases of WPV1 were reported, including 56 in Afghanistan (a 93% increase

from 29 cases in 2019) and 84 in Pakistan (a 43% decrease from 147 cases in 2019).

As GPEI focuses on the last endemic WPV reservoirs, poliomyelitis outbreaks caused

by circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV) have emerged as a result of attenuated

oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV) virus regaining neurovirulence after prolonged circulation

in underimmunized populations (

3

). In 2020, 32 countries reported cVDPV outbreaks (four type 1 [cVDPV1], 26 type 2

[cVDPV2] and two with outbreaks of both); 13 of these countries reported new outbreaks.

The updated GPEI Polio Eradication Strategy 2022–2026 (

4

) includes expanded use of the type 2 novel oral poliovirus vaccine (nOPV2) to avoid

new emergences of cVDPV2 during outbreak responses (

3

). The new strategy deploys other tactics, such as increased national accountability,

and focused investments for overcoming the remaining barriers to eradication, including

program disruptions and setbacks caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Polio Vaccination

In worldwide immunization programs, OPV and at least 1 dose of injectable, inactivated

poliovirus vaccine (IPV) are routinely used. Because IPV contains all three poliovirus

serotypes, it protects against disease in children who seroconvert after vaccination;

however, it does not prevent poliovirus transmission. In 2016, a global coordinated

switch occurred from trivalent OPV (tOPV), which contains Sabin strain types 1, 2,

and 3 to bivalent OPV (bOPV), which contains Sabin strain types 1 and 3. WPV2 was

declared eradicated in 2015, and cVDPV2 was the predominant cause of cVDPV outbreaks

after the last WPV2 case was detected in 1999. The use of monovalent OPV Sabin strain

type 2 (mOPV2) is reserved for cVDPV2 outbreak responses. In November 2020, the World

Health Organization (WHO) granted Emergency Use Listing (EUL) for genetically stabilized

nOPV2 to be used in a limited number of countries that have met readiness criteria

for initial use* of nOPV2 (

5

) in response to outbreaks.

In 2020, the estimated global infant coverage with 3 doses of poliovirus vaccine (Pol3)

by age 1 year was 83% (

6

). However, substantial variation in coverage exists by WHO region, nationally, and

subnationally. In the two countries with endemic WPV (Afghanistan and Pakistan), 2020

POL3 coverage was 75% and 83%, respectively (

6

); estimated coverage in subnational areas with transmission is much lower.

In 2019, GPEI supported 199 supplementary immunization activities (SIAs)

†

in 42 countries with approximately 1 billion bOPV, 20 million IPV, 32 million monovalent

OPV type 1 (mOPV1), and 142 million mOPV2 doses administered. In 2020, 149 SIAs were

conducted in 30 countries with approximately 696 million bOPV, 6 million IPV, 4 million

mOPV1, 228 million mOPV2, and 51 million tOPV doses administered; tOPV was used during

four SIAs in Afghanistan and Pakistan, where cocirculation of WPV1 and cVDPV2 requires

tOPV for efficiency in scheduling and implementing SIAs; GPEI authorized restarting

filling of tOPV stocks for this purpose. In 2021, approximately 136 million nOPV2

doses have been released in eight countries approved for initial use (Benin, Chad,

Congo, Liberia, Niger, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, and Tajikistan). SIAs continue to be

affected by the COVID-19 pandemic

§

in 2021.

Poliovirus Surveillance

WPV and cVDPV transmission are detected primarily through surveillance for acute flaccid

paralysis (AFP) among children aged <15 years with testing of stool specimens at one

of 145 WHO-accredited laboratories of the Global Polio Laboratory Network (

7

). During January–September 2020, the number of reported AFP cases declined 33% compared

with the same period in 2019 (

8

). Environmental surveillance (testing of sewage for poliovirus) can supplement AFP

surveillance; however, environmental sampling also declined somewhat during this period.

Current data indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic has continued to limit AFP surveillance

sensitivity. The continued strengthening of both surveillance systems, particularly

in priority countries,

¶

is critical to tracking progress and documenting the absence of poliovirus transmission.

Reported Poliovirus Cases and Isolations

Countries reporting WPV cases and isolations. Since 2016, no WPV cases have been identified

outside of Afghanistan and Pakistan. Of the 176 WPV1 cases reported in 2019, 29 (16%)

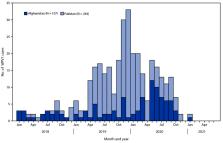

occurred in Afghanistan and 147 (84%) in Pakistan (Figure) (Table 1).

FIGURE

Number of wild poliovirus type 1 cases, by country and month of paralysis onset —

worldwide, January 2019—June 2021*

Abbreviation: WPV1 = wild poliovirus type 1.

* Data are current as of August 3, 2021.

The figure is a bar chart showing the number of wild poliovirus type 1 cases that

occurred worldwide during January 2019–June 2021, by country and month of paralysis

onset.

TABLE 1

Number of poliovirus cases, by country — worldwide, January 1, 2019–June 30, 2021*

Country (cVDPV type)

Reporting period

2019

2020

Jan–Jun 2020

Jan–Jun 2021

WPV1

cVDPV

WPV1

cVDPV

WPV1

cVDPV

WPV1

cVDPV

Countries with endemic WPV1 transmission

Afghanistan (2)†

29

0

56

308

34

54

1

43

Pakistan (2)

147

22

84

135

60

52

1

8

Countries with reported cVDPV cases

Angola (2)

0

138

0

3

0

3

0

0

Benin (2)

0

8

0

3

0

2

0

2

Burkina Faso (2)

0

1

0

65

0

26

0

1

Burma (Myanmar)(2)§

0

6

0

0

0

0

0

0

Cameroon (2)†

0

0

0

7

0

4

0

0

Central African Republic (2)

0

21

0

4

0

1

0

0

Chad (2)

0

11

0

99

0

57

0

0

China (2)

0

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

Republic of the Congo (2)†

0

0

0

2

0

0

0

2

Côte d’Ivoire (2)†

0

0

0

61

0

39

0

0

Democratic Republic of the Congo (2)

0

88

0

81

0

54

0

10

Ethiopia (2)

0

14

0

36

0

17

0

6

Ghana (2)

0

18

0

12

0

12

0

0

Guinea (2)†

0

0

0

44

0

23

0

6

Liberia (2)†

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

3

Madagascar (1)†

0

0

0

2

0

0

0

6

Malaysia (1)

0

3

0

1

0

1

0

0

Mali (2)†

0

0

0

48

0

6

0

0

Niger (2)

0

1

0

10

0

6

0

0

Nigeria (2)

0

18

0

8

0

2

0

65

Philippines (1,2)¶

0

14

0

1

0

1

0

0

Senegal (2)†

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

13

Sierra Leone (2)†

0

0

0

10

0

0

0

4

Somalia (2)

0

3

0

14

0

2

0

0

South Sudan (2)†

0

0

0

50

0

2

0

9

Sudan (2)†

0

0

0

58

0

10

0

0

Tajikistan (2)†

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

23

Togo (2)

0

8

0

9

0

9

0

0

Yemen (1)

0

1

0

31

0

22

0

3

Zambia (2)

0

2

0

0

0

0

0

0

Abbreviations: cVDPV = circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus; WPV1 = Wild poliovirus

type 1.

* Data are current as of August 3, 2021.

† New cVDPV cases reported after December 31, 2019.

§ For this country, MMWR uses the U.S. State Department short-form name “Burma”; the

World Health Organization uses “Myanmar.”

¶ Reported two cVDPV type 1 cases and 12 cVDPV type 2 cases in 2019, one cVDPV type

2 case in 2020.

In 2020, Afghanistan reported 56 WPV1 cases representing a 93% increase from cases

reported in the previous year; cases were found across 38 districts compared with

20 districts in 2019. As of August 3, 2021, one WPV1 case was reported in Afghanistan

in 2021, a 97% decrease compared with the first 6 months of 2020. Pakistan reported

84 WPV1 cases from 39 districts in 2020, representing a 43% decrease from the 147

cases reported in 43 districts during 2019. One WPV1 case has been reported during

January–June 2021, from Balochistan province, a 98% decrease from the 60 WPV1 cases

from five provinces during the same 2020 period. This period accounted for 71% of

all Pakistan WPV1 cases in 2020. In both countries, the number of orphan WPV1 isolates

(those with ≤98.5% genetic identity with other isolates) from AFP cases increased

from five of 176 (3%) in 2019 to 18 of 140 (13%) in 2020, signifying an increase in

AFP surveillance gaps in 2020 (

7

).

Environmental surveillance in Afghanistan detected WPV1 in 35 (8%) of 418 sewage samples

collected during 2020 and in 57 (22%) of 264 samples in 2019 (Table 2). In Pakistan,

WPV1 was detected in 434 (52%) of 830 sewage samples collected in 2020, and 44% (379/854)

of sewage samples were WPV1-positive in 2019. In 2019, three (4%) of the 71 sewage

samples collected in Iran contained WPV1 isolates; no positive environmental samples

or cases have been reported since then.

TABLE 2

Number of circulating wild polioviruses and circulating vaccine-derived polioviruses

detected through environmental surveillance — worldwide, January 1, 2019–June 30,

2021*

Country

Jan 1–Dec 31, 2019

Jan 1–Dec 31, 2020

Jan 1–Jun 30, 2020

Jan 1–Jun 30, 2021

No. of samples

No. (%) with isolates

No. of samples

No. (%) with isolates

No. of samples

No. (%) with isolates

No. of samples

No. (%) with isolates

Countries with reported WPV1-positive samples (no. and percentage of isolates refer

to WPV1)

Afghanistan

264

57 (22)

418

35 (8)

172

22 (13)

213

1 (1)

Iran

71

3 (4)

43

0 (—)

0

0 (—)

0

0 (—)

Pakistan

854

379 (44)

830

434 (52)

414

238 (57)

444

59 (13)

Countries with reported cVDPV-positive samples (cVDPV type) (no. and percentage of

isolates refer to cVDPVs)

Afghanistan (2)

264

0 (—)

418

175 (42)

172

46 (27)

213

40 (19)

Angola (2)

106

17 (16)

98

0 (—)

47

0 (—)

15

0 (—)

Benin (2)

37

0 (—)

70

5 (7)

31

0 (—)

52

1 (2)

Cameroon (2)

602

4 (1)

273

9 (3)

134

4 (3)

187

0 (—)

Central African Republic (2)

149

10 (7)

97

2 (2)

43

2 (5)

48

0 (—)

Chad (2)

198

10 (5)

77

3 (4)

55

3 (5)

26

0 (—)

China (3)

0

0 (—)

0

0 (—)

0

0 (—)

1

1 (100)

Republic of the Congo (2)

0

0 (—)

12

1 (8)

0

0 (—)

213

1 (1)

Cote d’Ivoire (2)

154

7 (5)

130

91 (70)

88

62 (70)

42

0 (—)

Democratic Republic of the Congo (2)

294

0 (—)

170

1 (1)

78

1 (1)

145

0 (—)

Egypt (2)

703

0 (—)

550

1 (0)

267

0 (—)

313

10 (3)

Ethiopia (2)

159

3 (2)

51

2 (4)

33

0 (—)

15

0 (—)

Gambia (2)

0

0 (—)

0

0 (—)

0

0 (—)

9

2 (22)

Ghana (2)

202

17 (8)

184

20 (11)

100

19 (19)

99

0 (—)

Guinea (2)

103

0 (—)

67

1 (1)

38

0 (—)

61

0 (—)

Iran (2)

74

0 (—)

43

3 (7)

12

0 (—)

25

1 (4)

Kenya (2)

317

0 (—)

193

1 (1)

92

0 (—)

101

1 (1)

Liberia (2)

0

0 (—)

34

6 (18)

15

0 (—)

47

12 (26)

Madagascar (1)

520

0 (—)

351

0 (—)

232

0 (—)

134

12(9)

Malaysia (1, 2)

13

12 (92)

76

12 (16)

50

12 (24)

22

0 (—)

Mali (2)

48

0 (—)

44

4 (9)

22

2 (9)

27

0 (—)

Niger (2)

293

0 (—)

157

7 (4)

93

1 (1)

73

0 (—)

Nigeria (2)

2071

60 (3)

1294

5 (0)

625

0 (—)

868

34 (4)

Pakistan (2)

855

36 (4)

830

135 (16)

414

35 (8)

444

32 (7)

Philippines (1, 2)

67

32 (48)

80

4 (5)

50

4 (8)

18

0 (—)

Senegal (2)

56

0 (—)

27

1 (4)

14

0 (—)

10

4 (40)

Somalia (2)

92

5 (5)

88

26 (30)

52

18 (35)

52

1 (2)

South Sudan (2)

111

0 (—)

85

6 (7)

57

0 (—)

24

0 (—)

Sudan (2)

65

0 (—)

50

14 (28)

20

3 (15)

30

0 (—)

Tajikistan (2)

0

0 (—)

0

0 (—)

0

0 (—)

14

13 (93)

Uganda (2)

56

0 (—)

58

0 (—)

24

0 (—)

36

2 (6)

Abbreviations: cVDPV = circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus; WPV1 = Wild poliovirus

type 1.

* Data are current as of August 3, 2021.

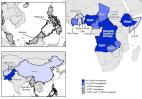

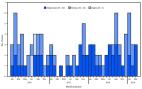

Countries reporting cVDPV cases and isolations. During January 2019–June 2021, cVDPV

transmission was identified in 32 countries; 13 countries were affected by new cVDPV

outbreaks in 2020. Afghanistan reported 308 cVDPV2 cases in 2020 compared with no

cases in 2019. Pakistan reported 135 cVDPV2 cases in 2020, more than a fivefold increase

from the 22 reported in 2019. To date in 2021, 195 cVDPV2 cases have been identified

globally, including 43 in Afghanistan and eight in Pakistan.

Discussion

With the August 2020 certification of the African Region as WPV-free,** five of the

six WHO regions, representing over 90% of the world’s population, are now free of

wild polioviruses. Given this achievement, GPEI is focusing efforts on two goals:

interrupting persistent WPV1 transmission in Pakistan and Afghanistan and stopping

all current outbreaks of cVDPV2. To reach these goals, in June 2021, GPEI released

a revised 5-year strategy for polio eradication that aims to address persistent challenges

and recover from setbacks exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic (

4

).

Guided by the Polio Eradication Strategy 2022–2026, GPEI partners and in-country stakeholders

are to adopt a full emergency posture and assume more accountability for eradication

at every level of the program (

4

). The strategy elevates efforts in the highest-risk countries and promotes health

service integration, surveillance improvement, and community engagement to enhance

campaign quality through increased political advocacy to ensure timely and effective

emergency outbreak SIA responses through improved government support of implementation.

Although Pakistan and Afghanistan face distinct challenges, they are linked epidemiologically

because of high rates of cross-border population movement. Transit-point vaccination

must be maintained as emigration from Afghanistan potentially increases in 2021. The

beginning of each year is typically the low season for WPV1 transmission in both countries,

and AFP surveillance sensitivity has decreased. During 2019, the Pakistan polio program

suffered from increased vaccine resistance fed by social media misinformation and

faced continued operational problems in some localities. The program changed its management

oversight and enhanced efforts to overcome community mistrust to decrease vaccine

hesitancy (

9

). Inroads to improving the effectiveness of the SIAs have also been made in 2020

(

4

). Although the proportion of Pakistan environmental samples that are WPV-positive

remains high in 2021 to date, the decrease from the same period in 2020 is worth noting.

In Afghanistan, the main challenges to ending poliovirus transmission are the inability

to reach all children in critical areas near reservoirs in Pakistan and increasing

political instability. The polio program in Afghanistan has continued to operate for

many years, even during periods of insecurity and escalating conflict. Although negotiations

with local leaders in Afghanistan facilitated vaccination efforts at one time, restrictions

on vaccinations have persisted in areas controlled by insurgent groups since the October

2018 ban on house-to-house campaigns, which has since expanded geographically (

10

). WHO is anticipating that some negotiated access will again be possible. Other challenges

include current mass population movements, clusters of vaccine refusals, and suboptimal

SIA quality in some areas previously under government control (

10

).

Globally, cVDPV2 outbreaks increased in number and geographic extent during 2019–2020

because of delays in mOPV2 response SIAs, which were frequently of low quality. Since

the switch in 2016 from tOPV to bOPV, 1,755 cases of paralytic polio have been reported

from 64 cVDPV2 outbreaks in 30 countries across four WHO regions (

4

).

††

GPEI has outlined a strategy for stopping cVDPV transmission and reducing the risk

of seeding new outbreaks by expanding use of nOPV2 (

4

). Continued monitoring will be needed to ensure safety and effectiveness while nOPV2

is brought into wider use and to ascertain whether it can replace mOPV2 (

5

).

The findings in this report are subject to at least one limitation. SIAs, field surveillance,

and investigation activities were curtailed in 2020 because of COVID-19 pandemic mitigation

measures, and laboratory testing suffered delays (

8

); limitations on SIA quality and surveillance sensitivity continue in 2021. On the

other hand, the COVID-19 pandemic has presented opportunities to jointly increase

the effectiveness of polio eradication activities and promote health services integration.

For example, the global rollout of COVID-19 vaccines presents an opportunity to strengthen

demand for vaccination against both COVID-19 and polio.

Thousands of polio eradication workers worldwide continue to play a critical role

in implementing countries’ COVID-19 responses. Maintaining these partnerships will

be important in eradicating WPV and stopping cVDPV transmission while simultaneously

addressing other health priorities.

Summary

What is already known about this topic?

Wild poliovirus type 1 (WPV1) remains endemic in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Circulating

vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (cVDPV2) outbreaks have increased since 2017.

What is added by this report?

From 2019 to 2020, the number of WPV1 cases increased in Afghanistan and decreased

in Pakistan and the number of cVDPV2 cases increased and cVDPV2 outbreak countries

increased to 32. In Afghanistan, the polio program faces challenges including an inability

to reach children in critical areas and increasing political instability. The COVID-19

pandemic continues to limit the quality of immunization activities and poliovirus

surveillance.

What are the implications for public health practice?

The Polio Eradication Strategy for 2022–2026 outlines measures including increased

government accountability and wider use of novel, oral poliovirus vaccine type 2 that

are needed to eradicate polio.

Related collections

Most cited references6

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Update on Vaccine-Derived Poliovirus Outbreaks — Worldwide, July 2019–February 2020

Mary Alleman, Jaume Jorba, Sharon A. Greene … (2020)

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Progress Toward Polio Eradication — Worldwide, January 2018–March 2020

Anna N. Chard, S Datta, Graham Tallis … (2020)

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Progress Toward Polio Eradication — Worldwide, January 2017–March 2019

Sharon A. Greene, Jamal Ahmed, S Datta … (2019)