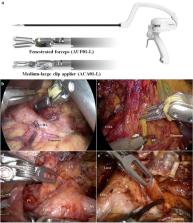

INTRODUCTION Background Gastric cancer is the most common cancer and the fourth most common cause of cancer death in South Korea [1]. Despite the large number of gastric cancer patients newly diagnosed and treated annually in South Korea, there has been no appropriate practice guideline for domestic medical situations. Although Korean guidelines for gastric cancer were published through interdisciplinary collaborations in 2004 and 2014 [2 3], they were not widely used in South Korea. Therefore, we have produced the present clinical practice guideline to create guidelines that can provide the standard of gastric cancer treatment in accordance with the medical reality in South Korea. Scope The present clinical practice guideline is intended for physicians to treat patients with gastric cancer. This guideline is specific and comprehensive for gastric cancer treatment and pathological evaluations; however, it does not address issues related to prevention, screening, diagnosis, and postoperative follow-up. It is based on domestic and overseas evidence and has been developed to be applied to Korean gastric cancer patients under the current medical situation and to ensure their widespread adoption in clinical practice. This guideline is intended to help medical staffs and educate training physicians at secondary and tertiary care medical institutions, including endoscopists, surgeons, medical oncologists, radiology oncologists, and pathologists. Additionally, the guideline was designed to allow patients and populations to receive optimum care by providing adequate medical information. Furthermore, it is intended for widespread adoption to increase the standard of gastric cancer treatment, thereby contributing to improving patient quality of life as well as national health care. Chronology The present guideline was initiated by the Korean Gastric Cancer Association (KGCA) based on the consensus for national need with the associated academic societies. This guideline was prepared in an integrated and comprehensive manner through an interdisciplinary approach that included the KGCA, the Korean Society of Medical Oncology (KSMO), the Korean Society of Gastroenterology (KSG), the Korean Society for Radiation Oncology (KOSRO), and the Korean Society of Pathologists (KSP), along with the participation of experts in the methodology of guideline development (National Evidence-based Healthcare Collaborating Agency). To complete this guideline, the Guideline Committee of the KGCA established the Development Working Group and Review Panel for Korean Practice Guidelines for Gastric Cancer 2018. The members were nominated by each participant association and society. This guideline will be revised every 3 to 5 years when there is solid evidence that can affect the outcomes of patients with gastric cancer. Method We systematically searched published literature using databases including MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library through January 2018. Manual searches were also performed to complement the results. The selection of relevant studies was performed by panels composed of pairs of clinical experts. The selection and exclusion criteria were predefined and tailored to key questions. The articles were screened by title and abstract and full texts were then retrieved for selection. In each step, 2 panels were independently selected and reached agreements. We critically appraised the quality of the selected studies using risk-of-bias tools. We used Cochrane Risk of Bias (ROB) for randomized controlled trials (RCTs), ROB for Nonrandomized Studies for non-RCTs, Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2 for diagnostic studies, and A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews for systematic reviews/meta-analysis [4 5 6 7]. The panels independently assessed and reached a consensus. Disagreements were resolved by discussion and the opinion of a third member. We extracted data using a predefined format and synthesized these data qualitatively. Evidence tables were summarized according to key questions. The levels of evidence and grading of the recommendations were modified based on the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network and Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology reviews [8 9]. The evidence was classified into 4 levels. The main factors were study design and quality (Table 1). Additionally, we considered outcome consistency. The grading of the recommendations was performed according to a modified GRADE methodology into 5 levels including strong for, weak for, weak against, strong against, and inconclusive (Table 2). The recommendation factors considered evidence level, clinical applicability, and benefit and harm. The Development Working Group simultaneously reviewed the draft and discussed for consensus. Table 1 Levels of evidence Class Explanation High At least 1 RCT or SR/meta-analysis with no concern regarding study quality Moderate At least 1 RCT or SR/meta-analysis with minor concern regarding study quality or at least 1 cohort/case-control/diagnostic test design study with no concern regarding study quality Low At least 1 cohort/case-control/diagnostic test study with minor concern regarding study quality or at least 1 single arm before-after study, cross-sectional study with no concern regarding study quality Very low At least 1 cohort/case-control/diagnostic test design study with serious concern regarding study quality or at least 1 single arm before-after study, cross-sectional study with minor/severe concern regarding study quality Table 2 Grading of recommendations Grade classification Explanation Strong for The benefit of the intervention is greater than the harm, with high or moderate levels of evidence. The intervention can be strongly recommended in most clinical practice. Weak for The benefit and harm of the intervention may vary depending on the clinical situation or patient/social value. The intervention is recommended conditionally according to the clinical situation. Weak against The benefit and harm of the intervention may vary depending on the clinical situation or patient/social values. The intervention may not be recommended in clinical practice. Strong against The harm of the intervention is greater than the benefit, with high or moderate levels of evidence. The intervention should not be recommended in clinical practice. Inconclusive It is not possible to determine the recommendation direction owing to a lack of evidence or a discrepancy in results. Thus, further evidence is needed. Review and approval process The Review Panel examined the final version of the draft by careful expert review. Revisions were made reflecting the Review Panel's opinions. The guideline was then approved by the KSMO, the KSP, the KSG, the KOSRO, and the KGCA at a Korean Gastric Cancer Guideline Presentation Symposium held on 30th November 2018. OVERALL TREATMENT ALGORITHM All statements in this guideline are summarized in Table 3. The tumor description was confined to adenocarcinoma and the tumor status (TNM and stage) was based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC)/Union for International Cancer Control 8th edition [10]. Table 3 Summary of statements No. Recommendations Level of evidence Grade of recommendation Statement 1 Endoscopic resection is recommended for well or moderately differentiated tubular or papillary early gastric cancers meeting the following endoscopic findings: endoscopically estimated tumor size ≤2 cm, endoscopically mucosal cancer, and no ulcer in the tumor. Moderate Strong for Statement 2 Endoscopic resection could be performed for well or moderately differentiated tubular early gastric cancer or papillary early gastric cancers with the following endoscopic findings: endoscopically estimated tumor size >2 cm, endoscopically mucosal cancer, and no ulcer in the tumor or endoscopically estimated tumor size ≤3 cm, endoscopically mucosal cancer, and ulcer in the tumor. Moderate Weak for Statement 3 Endoscopic resection could be considered for poorly differentiated tubular or poorly cohesive (including signet-ring cell) early gastric cancers meeting the following endoscopic findings: endoscopically estimated tumor size ≤2 cm, endoscopically mucosal cancer, and no ulcer in the tumor. Low Weak for Statement 4 After endoscopic resection, additional curative surgery is recommended if the pathologic result is beyond the criteria of the curative endoscopic resection or if lymphovascular or vertical margin invasion is present. Moderate Strong for Statement 5 Proximal as well as total gastrectomy could be performed for early gastric cancer in terms of survival rate, nutrition, and quality of life. Esophagogastrostomy after proximal gastrectomy can result in more anastomosis-related complications including stenosis and reflux; caution is needed in the selection of reconstruction method. Moderate Weak for Statement 6 PPG could be performed for early gastric cancer as well as DG in terms of survival rate, nutrition, and quality of life. Moderate Weak for Statement 7 Gastroduodenostomy and gastrojejunostomy (Roux-en-Y and loop) are recommended after DG in middle and lower gastric cancers. There are no differences in terms of survival, function, and nutrition between the different types of reconstruction. High Strong for Statement 8 D1+ is recommended during the surgery for early gastric cancer (cT1N0) patients in terms of survival. Low Strong for Statement 9 Prophylactic splenectomy for splenic hilar LND is not recommended during curative resection for advanced gastric cancer in the proximal third stomach. High Strong against Statement 10 Lower mediastinal LND could be performed to improve oncologic outcome without increasing postoperative complications for adenocarcinoma of the EGJ. Low Weak for Statement 11 Laparoscopic surgery is recommended in early gastric cancer for postoperative recovery, complications, quality of life, and long-term survival. High Strong for Statement 12 Laparoscopic gastrectomy could be performed for advanced gastric cancer in terms of short-term surgical outcomes and long-term prognosis. Moderate Weak for Statement 13 Adjuvant chemotherapy (S-1 or capecitabine plus oxaliplatin) is recommended in patients with pathological stage II or III gastric cancer after curative surgery with D2 LND. High Strong for Statement 14 Adjuvant chemoradiation could be added in gastric cancer patients after curative resection with D2 lymphadenectomy to reduce recurrence and improve survival. High Weak for Statement 15 Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for potentially resectable gastric cancer is not conclusive if D2 LND is considered. High Inconclusive Statement 16 The evidence for the effectiveness of neoadjuvant chemoradiation in locally advanced gastric cancer is not conclusive if D2 LND is considered. High Inconclusive Statement 17 Palliative gastrectomy is not recommended for metastatic gastric cancer except for palliation of symptoms. High Strong against Statement 18-1 Palliative first-line combination platinum/fluoropyrimidine is recommended in patients with locally advanced unresectable or metastatic gastric cancer if the patient's performance status and major organ functions are preserved. High Strong for Statement 18-2 Palliative trastuzumab combined with capecitabine or fluorouracil plus cisplatin is recommended in patients with HER2 IHC 3+ or IHC 2+ and ISH-positive advanced gastric cancer. High Strong for Statement 19 Palliative second-line systemic therapy is recommended in patients with locally advanced unresectable or metastatic gastric cancer if the patient's performance status and major organ functions are preserved. Ramucirumab plus paclitaxel is preferably recommended and monotherapy with irinotecan, docetaxel, paclitaxel, or ramucirumab could also be considered. High Strong for Statement 20 Palliative third-line systemic therapy is recommended in patients with locally advanced unresectable or metastatic gastric cancer if the patient's performance status and major organ functions are preserved. High Strong for Statement 21 Palliative RT could be offered to alleviate symptoms and/or improve survival in recurrent or metastatic gastric cancer. Moderate Weak for Statement 22 Peritoneal washing cytology is recommended for staging. Advanced gastric cancer patients with positive cancer cells in the peritoneal washing cytology are associated with frequent cancer recurrence and a poor prognosis. Moderate Strong for PPG = preserving gastrectomy; DG = distal gastrectomy; LND = lymph node dissection; EGJ = esophagogastric junction; IHC = immunohistochemistry; ISH = in situ hybridization; RT = radiotherapy. Gastric adenocarcinoma was divided into localized (non-metastatic [M0]) and metastatic-1 (M1) disease according to the status of distant metastasis (Fig. 1). Fig. 1 Overall treatment algorithm. Diff. = differentiated; Undiff. = undifferentiated. In cases of M0 gastric cancer, clinical (c) T- and N-stages can be determined based on preoperative esophagogastroduodenoscopy or endoscopic ultrasound examination findings and computed tomography. Endoscopic resection can be indicated for selected cT1aN0 gastric cancer with minimal risk of lymph node (LN) metastasis (statements 1–3). The necessity of additional curative gastrectomy after endoscopic treatment is determined based on the pathologic review of the endoscopic resection specimen (statement 4). Surgical resection is recommended if the tumor is outside of endoscopic resection indications in cT1a and ≥cT1b or cN+. The extent of gastrectomy (statements 5 and 6) and lymphadenectomy (statements 8, 9, and 10), reconstruction methods (statement 7), and approach methods (statements 11 and 12) should be considered when deciding surgical procedures. Adjuvant chemotherapy is recommended in patients with pathological stage II or III gastric cancer after curative R0 resection with D2 LN dissection (LND) (statement 13). Adjuvant chemoradiation can be considered in patients with incomplete resection, including R1 resection and/or less than D2 LND, and after curative R0 resection with D2 LND, especially with LN metastasis (statement 14). When the result of primary gastrectomy is R1 resection, 3 treatment options can be considered, according to the location of microscopic residual tumor: re-resection, adjuvant chemoradiotherapy, or palliative therapy, depending on the clinical situation. Although neoadjuvant chemo (radio) therapy has high levels of evidence, we did not reach a conclusion on whether to recommend it in Asian populations because the backgrounds of almost all clinical trials on preoperative therapy were not consistent with Asian situations (statements 15 and 16). Palliative systemic therapy is the primary treatment to be considered in patients with locally advanced unresectable or those after non-curative resection or metastatic disease (M1) (statements 18–20). Palliative radiotherapy (RT) can be considered for the alleviation of tumor-related symptoms or to improve survival (statement 21); however, palliative gastrectomy not intended to alleviate tumor-related symptoms or complications (i.e., obstruction, bleeding, perforation, etc.) is not recommended for the purpose of improving overall survival (OS) (statement 17). ENDOSCOPIC RESECTION Statement 1. Endoscopic resection is recommended for well or moderately differentiated tubular or papillary early gastric cancers meeting the following endoscopic findings: endoscopically estimated tumor size ≤2 cm, endoscopically mucosal cancer, and no ulcer in the tumor (evidence: moderate, recommendation: strong for). Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) has been used as a minimally invasive treatment modality for early gastric cancer since the early 2000s in Korea [11 12]. A total of 7,734 early gastric cancer patients underwent ESD in 2014 [12]. Many studies have indicated that ESD should be considered as the first-line treatment modality for the early gastric cancer with well or moderately differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma or papillary adenocarcinoma with tumor size ≤2 cm, confined to the mucosal layer, and without ulcer in the tumor as these findings definitely indicated that the lesions had a very low-risk of LN metastasis [13 14] and ESD allows high rates of en bloc curative resection with low adverse event rates [11 14 15 16 17 18] (Fig. 2). Fig. 2 Treatment algorithm for endoscopic resection. Diff. = differentiated; Undiff. = undifferentiated; ESD = endoscopic submucosal dissection. The 5-year OS rates of patients meeting this definite indication for ESD did not differ significantly from those of patients who received endoscopic resection (93.6%–96.4%) and surgery (94.2%–97.2%) in large retrospective cohort studies in Korea [16 17 18]. The 10-year OS rates were comparable between endoscopic resection (81.9%) and surgery (84.9%) (P=0.14) [17]. However, the 5-year cumulative metachronous recurrence rates were significantly higher after endoscopic resection (5.8%–10.9%) than those after surgery (0.9%–1.1%) [16 17 18]. Therefore, close surveillance should be performed after ESD to detect early-stage metachronous gastric cancer that can be treated with endoscopic resection. Nevertheless, endoscopic treatment for early gastric cancer can provide a better quality of life, though stomach preservation might provoke worries of metachronous cancer recurrence [19]. Moreover, ESD had lower treatment-related complication rates [17 18], shorter hospital stay, and lower costs than those of surgery [16]. In the aspect of patient preference, ESD can provide better health-related quality of life for early gastric cancer patients, especially in terms of physical function, eating limits, dyslexia, diarrhea, and body image [20]. Statement 2. Endoscopic resection could be performed for well or moderately differentiated tubular early gastric cancer or papillary early gastric cancers meeting the following endoscopic findings: endoscopically estimated tumor size >2 cm, endoscopically mucosal cancer, and no ulcer in the tumor or endoscopically estimated tumor size ≤3 cm, endoscopically mucosal cancer, and ulcer in the tumor (evidence: moderate, recommendation: weak for). Endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer is limited in that LND cannot be performed during the procedure. Therefore, to achieve curative resection and comparable survival to that of surgery with endoscopic resection, early gastric cancers with very low-risk of LN metastasis should be carefully selected. The clinically acceptable rate of LN metastasis might be determined in the context of perioperative mortality associated with radical gastrectomy (0.1%–0.3% in a high-volume center in Korea and Japan) [21 22 23]. In addition, it is required that en bloc resection is technically feasible with endoscopic resection to avoid the possibility of remnant tumor or local recurrence after the procedure. When the following criteria 1 or 2 were met, the extragastric recurrence (LN or distant metastasis) rate after endoscopic resection was between 0 and 0.21%, which is comparable to that of perioperative mortality associated with radical gastrectomy [24 25 26 27]. Although standard gastrectomy with LND is recommended when submucosal invasion of the tumor (T1b) is suspected in preoperative evaluation, the extragastric recurrence rate after ESD ranged from 0.9% to 1.5% in large retrospective cohort studies when the pathologic specimen of ESD fulfilled criteria 3 [24 25 26]. Because the diagnosis of minute submucosal invasion (≤500 µm) of the tumor before ESD is very difficult, criteria 3 applies to post-ESD pathologic specimens. When criteria 1, 2, or 3 were met, the OS was comparable between patients undergoing endoscopic resection and those treated with radical surgery [18 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38]. Criteria 1, 2, and 3: well or moderately differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma or papillary adenocarcinoma, en bloc resection, negative lateral resection margins, negative vertical resection margin, no lymphovascular invasion (LVI), and 1) tumor size >2 cm, mucosal cancer, no ulcer in the tumor, or 2) tumor size ≤3 cm, mucosal cancer, ulcer in the tumor, or 3) tumor size ≤3 cm, submucosal invasion depth ≤500 μm from the muscularis mucosa layer. Because many the factors of these criteria can be confirmed after ESD (i.e., en bloc resection, resection margin, LVI, and minute submucosal invasion), ESD can be considered if the early gastric cancer meets the following endoscopic findings: 1) Well or moderately differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma or papillary adenocarcinoma on forceps biopsy specimen, endoscopically estimated tumor size >2 cm, endoscopically mucosal cancer, and no ulcer in the tumor, or 2) Well or moderately differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma or papillary adenocarcinoma on forceps biopsy specimen, endoscopically estimated tumor size ≤3 cm, endoscopically mucosal cancer, and ulcer in tumor (Fig. 2). Until now, the standard treatment for these criteria has been gastrectomy with LND. Although a number of retrospective cohort studies support these criteria, no prospective trial has compared the outcomes of endoscopic resection with those of standard operation based on these criteria. A significant portion of these criteria estimated by pre-ESD workup is confirmed to be out of criteria by the pathologic examination of ESD specimens [39 40 41 42 43]. Thus, standard operation (gastrectomy with LND) may also be considered for cases meeting these criteria. Statement 3. Endoscopic resection could be considered for poorly differentiated tubular or poorly cohesive (including signet-ring cell) early gastric cancers meeting the following endoscopic findings: endoscopically estimated tumor size ≤2 cm, endoscopically mucosal cancer, and no ulcer in the tumor (evidence: low, recommendation: weak for). Poorly-differentiated tubular and poorly cohesive (including signet-ring cell) early gastric cancers are associated with a higher risk of LN metastasis than those of well and moderately differentiated tubular early gastric cancer. Thus, endoscopic resection can be considered very cautiously within strict criteria. When the following criteria were fulfilled, a few retrospective cohort studies reported extragastric recurrence after endoscopic resection [24 26 44 45 46 47 48 49] and a comparable OS between patients undergoing endoscopic resection and those treated with radical gastrectomy [18 29 35 36 49]. Poorly differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma or poorly cohesive carcinoma (including signet-ring cell carcinoma), en bloc resection, negative lateral resection margins, negative vertical resection margin, no LVI, and tumor size ≤ 2 cm, mucosal cancer, and no ulcer in the tumor. Because many factors of these criteria can be confirmed after ESD (i.e., en bloc resection, resection margin, and LVI), ESD can be considered for poorly-differentiated tubular and poorly cohesive (including signet-ring cell) early gastric cancers meeting the following endoscopic findings (Fig. 2). Poorly differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma or poorly cohesive carcinoma (including signet-ring cell carcinoma) on forceps biopsy specimen, endoscopically estimated tumor size ≤2 cm, endoscopically mucosal cancer, and no ulcer in the tumor. Until now, the standard treatment for these criteria has been gastrectomy with LND. A few retrospective cohort studies support these criteria for ESD and the results of prospective trials are lacking (level of evidence is low, and the level of recommendation is weak). A significant portion of these criteria estimated by pre-ESD workup is confirmed to be out of criteria by the pathologic examination of ESD specimens [39 40 41 42 43]. Thus, standard operation (gastrectomy with LND) can also be considered for cases meeting these criteria. Statement 4. After endoscopic resection, additional curative surgery is recommended if the pathologic result is beyond the criteria of the curative endoscopic resection or if lymphovascular or vertical margin invasion is present (evidence: moderate, recommendation: strong for). Early gastric cancer patients who received endoscopic resection could be considered as being beyond the criteria of endoscopic resection by pathologic specimen evaluation. Resected tumor characteristics beyond the following criteria are also considered for non-curative resection: 1) Differentiated (well or moderately differentiated tubular or papillary) intramucosal cancer measuring >2 cm in the long diameter without ulcer (active or scar), 2) differentiated mucosal cancer measuring 75 years) is controversial. Two studies showed a significant survival benefit but another study showed no difference in long-term outcomes [42 54 56]. Selection bias is inevitable in retrospective cohort designs. For example, all studies showed a younger age in the additional curative surgery group compared to that in the follow-up group, although the age difference disappeared after propensity score matching in 2 studies. Patients undergoing noncurative resection without additional curative surgery also tended to have a higher incidence of comorbidity [41 42]. Although 2 of 12 studies used propensity score matching analysis, selection and measurement biases are still possible. Additional curative surgery may be not feasible in some patients because of very old age, poorly-controlled underlying diseases, or poor general condition. In these patients, follow-up observation could be a feasible option after they are provided an explanation of the risk of recurrence. SURGICAL THERAPY Standard surgery is recommended in cases of cT1a, which are outside of the indication for endoscopic resection, and ≥cT1b or cN+ and M0 gastric cancer (Fig. 3A). Fig. 3 (A) Treatment algorithm for resectable gastric adenocarcinoma. (B) Treatment algorithm for resectable esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma. ESD = endoscopic submucosal dissection; LND = lymph node dissection. Standard surgery is defined as total or subtotal gastrectomy with D2 LND. Subtotal gastrectomy in distal gastric cancer has been recognized as a standard surgery based on the results of 2 RCTs in which the subtotal gastrectomy group showed similar long-term oncologic results and lower morbidity and mortality rates compared to those in the total gastrectomy group [58 59 60]. Although the standard extent of LND has been debated for decades among Eastern and Western countries, there has been an international trend to accept D2 LND as a standard surgery [2 61 62 63], which was supported by results of prospective trials and meta-analyses [64 65 66]. The extent of LND in each gastrectomy was defined according to Japanese guidelines [63]. Palliative systemic therapy is the primary treatment in cases of locally advanced unresectable or cM1 gastric cancer (Fig. 1). However, conversion surgery could be considered if R0 resection is possible after palliative systemic therapy, which is currently under investigation. Surgery with curative intent could also be considered in cases of locally advanced unresectable or cM1 gastric cancer not detected in preoperative evaluation but incidentally identified during surgery and if R0 resection is possible, which should be investigated in future studies. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy with or without hyperthermia could be applied to patients with peritoneal metastasis in a clinical trial setting; however, this requires additional evidence. Gastric resection and reconstruction Statement 5. Both proximal and total gastrectomy could be performed for early gastric cancer in terms of survival rate, nutrition, and quality of life. Esophagogastrostomy after proximal gastrectomy can result in more anastomosis-related complications including stenosis and reflux, and caution is needed in the selection of reconstruction method (evidence: moderate, recommendation: weak for). A prospective randomized controlled study comparing proximal and total gastrectomy with sufficient numbers of cases and power to evaluate the survival rate as the primary endpoint has not been conducted. However, several retrospective studies reported non-inferior long-term survival rates after proximal gastrectomy as compared to that of total gastrectomy [67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74]. In addition, the incidences of early postoperative complications after proximal gastrectomy were similar to those after total gastrectomy in most studies [68 70 71 73 75 76 77]; however, they have also been reported to be more [72] and less [69] frequent. Although various reconstructions after proximal gastrectomy have been tried in order to reduce short- or long-term complications, they remain controversial. Esophagogastrostomy after proximal gastrectomy is the simplest procedure but resulted in significantly more frequent reflux esophagitis (16.2%–42.0% vs. 0.5%–3.7%) and symptoms of reflux [67 69 72 74 76 77], as well as stenosis at the anastomosis site (3.1%–38.2% vs. 0%–8.1%) [67 69 71 72 74 76 77]. An et al. [69] and Ahn et al. [70] concluded that proximal gastrectomy with esophagogastrostomy is an inferior surgical method to total gastrectomy due to the significantly higher incidence of anastomosis-related and/or postoperative complications and no nutritional benefit. However, other studies have reported that proximal gastrectomy with esophagogastrostomy can be still beneficial compared to total gastrectomy in terms of serum albumin level [71 72 77], maintenance of body weight [74 76 77 78], prevention of anemia [72 74 77], and serum vitamin B12 level [72]. Jejunal interposition could be another option after proximal gastrectomy. Anastomosis with jejunal interposition has been shown to be beneficial in the context of nutritional parameters and anemia [71 74 75 76]. Postgastrectomy syndrome including dumping syndrome occurred less frequently in patients who underwent proximal gastrectomy with jejunal interposition compared to that in patients who underwent total gastrectomy [75 76]. A study including 115 cases that received esophagogastrostomy and 78 that received jejunal interposition also reported less frequent diarrhea and dumping syndrome for proximal gastrectomy (2.0 vs. 2.3 points on a 7-point scale) [78]. Recently, double-tract reconstruction after proximal gastrectomy has been proposed as an option that did not increase the incidence of complications or reflux and showed superiority to total gastrectomy in terms of body weight, anemia, and serum vitamin B12 level [73]. A multicenter prospective randomized clinical trial was launched in 2016 in Korea based on this result (NCT02892643). The incidence of metachronous cancer in the remnant stomach after proximal gastrectomy was 33.1% (6/192) and 6.2% (4/65) in reports by Huh et al. [72] and Ohashi et al., [76] respectively. In conclusion, proximal gastrectomy is a surgical option with possible benefits in aspects of shorter operative time, less blood loss, better maintenance of postoperative nutrition, lower incidence of anemia, better maintenance of vitamin B12 level, and lower incidence of post-gastrectomy syndrome (Fig. 3A). However, proximal gastrectomy requires caution in the choice of reconstruction technique because of the significantly increased incidence of anastomosis-related complications and reflux to the esophagus after esophagogastrostomy. Statement 6. Pylorus-preserving and distal gastrectomy (DG) could be performed for early gastric cancer in terms of survival rate, nutrition, and quality of life (evidence: moderate, recommendation: weak for). Conventional DG and pylorus-preserving gastrectomy (PPG) can be performed for middle-third early gastric cancer. PPG preserves the pre-pyloric antrum and the pylorus to prevent the rapid transit of food into the duodenum and reflux of the duodenal contents. Consequently, the postoperative incidence of dumping syndrome and reflux gastritis is decreased, and a nutritional benefit is expected. Most of the literature on PPG is retrospective studies. All studies that assessed the long-term survival concluded that there was no difference in long-term survival between conventional DG and PPG (5-year survival rates: 95% for PPG vs. 87% for DG, P=0.087 [79]; 3-year survival rates: 98.2% for PPG vs. 98.8% for DG, P=0.702 [80]; odds ratio [OR] of PPG, 0.83, 95% CI, 0.10–6.66, P=0.86 [81]; hazard ratio [HR] for recurrence in PPG, 0.393, 95% CI, 0.116–1.331, P=0.12 [82]). In addition, except for 1 report from Japan [79], most of the reports concluded that there was no difference in the incidence of postoperative complications [80 81]. As expected, after PPG, patients showed a significantly low incidence of postoperative dumping syndrome and reflux (reflux: 4% for PPG vs. 40% for DG; reflux gastritis: 8% for PPG vs. 68% for DG [83]; dumping syndrome: OR, 0.02, 95% CI, 0.10–0.41, P 50% of tumor lesions with an extracellular mucin pool regardless of the tumor cell type, signet ring cell or not [233]. 4) Poorly cohesive carcinoma This tumor is composed of poorly cohesive neoplastic cells that are isolated or form small aggregates [233]. This type includes signet ring cell carcinoma and other cellular variants composed of poorly cohesive neoplastic cells [233]. However, signet ring cell carcinoma is usually diagnosed separately if the signet ring cell component exceeds 50% rather than diagnosed as poorly cohesive carcinoma. 5) Mixed carcinoma This type of carcinoma has a discrete mixture of both glandular (tubular or papillary) and signet ring/poorly cohesive components [233]. The latter component is associated with a poor prognosis [233]. Addendum: In Japan, gastric carcinomas are commonly divided into 2 major categories, differentiated and undifferentiated types, especially with respect to the indications for endoscopic resection [237 238]. Although the WHO classifications do not completely match to this classification, the differentiated type generally includes well and moderately differentiated tubular adenocarcinomas and papillary adenocarcinoma, while the undifferentiated type includes poorly differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma and poorly cohesive carcinoma. Mucinous adenocarcinoma is classified as differentiated (with tubules) or undifferentiated (with signet ring cells) according to the type of tumor cell and is sometimes also categorized as undifferentiated type. Lauren classifications The Lauren classification divides tumors into intestinal, diffuse, and mixed types [234]. Intestinal carcinomas form glands with various degrees of differentiation and are almost invariably associated with intestinal metaplasia and variable degrees of atrophic gastritis. Diffuse carcinoma consists of poorly cohesive cells with little or no gland formation. Tumors containing approximately equal quantities of intestinal and diffuse components are termed “mixed.” Pathologic diagnosis of mixed histology In early gastric cancer, the histologic type and grade of the biopsy tissue are important for determining the treatment modality. Tumor heterogeneity and inter- and intra-observer discrepancies may lead to differences in histological types before and after ESD [239 240 241]. Submucosal and even intramucosal cancer with heterogeneity have recently been reported to have a higher incidence of LN metastasis than that of homogeneously differentiated types of tumor [242 243]. Thus, there is a view that the minor component of undifferentiated histology should be reported in cases of biopsy and ESD specimens. However, this requires more discussion and consensus of clinical and pathologic departments. Biomarkers HER2 IHC tests should first be performed for evaluation of HER2 status. IHC results are scored as 0, 1+, 2+, or 3+ (Table 4). IHC 3+ is considered positive for HER2 overexpression, while IHC 0-1+ is considered negative. IHC 2+ is regarded as an equivocal finding and should be followed by ISH tests. The area with the strongest IHC intensity should be selected and stained for HER2 and chromosome enumeration probe (CEP) 17. The criteria for HER2 amplification is a HER2:CEP17 ratio of ≥2. If CEP17 polysomy is present and the ratio is 6 is interpreted as a positive finding. IHC 3+ or IHC 2+ and ISH-positivity are considered HER2-positive [244 245]. HER2-positivity is an indication for anti-HER2 targeted therapy in the palliative setting [208]. Table 4 Interpretation of IHC findings [244 245] HER2 status Intensity IHC staining Negative 0 Reactivity in 1% vs. ≤1% but the median survival increased regardless of PD-L1 level [223]. Peritoneal washing cytology Statement 22. Peritoneal washing cytology is recommended for staging. Advanced gastric cancer patients with positive cancer cells in the peritoneal washing cytology are associated with frequent cancer recurrence and poor prognosis (evidence: moderate, recommendation: strong for). The association between peritoneal washing cytology results and prognosis in patients with advanced gastric cancer has been reported in prospective [259 260] and retrospective [261 262 263 264] studies but not in any randomized case-control studies. The exact prognostication of advanced gastric cancer patients with positive peritoneal washing cytology result is difficult due to variability in enrolled patients, peritoneal washing methods, and treatment of cancer patients in these studies. Recent systemic reviews and meta-analyses have shown that peritoneal washing cytology is useful for determining the prognosis of advanced gastric cancer patients [265 266 267 268]. Although some studies have reported that peritoneal washing cytology results are not related to prognosis, most studies and meta-analyses have observed a high recurrence rate and short survival time in advanced gastric cancer patients with positive washing cytology. In 2 meta-analyses, the HRs for survival among cytology-positive patients were 3.27 (95% CI, 2.82–3.78) [267] and 3.46 (95% CI, 2.77–4.31) [265], respectively, which was significantly higher than those for cytology-negative patients. The HR of cancer recurrence (4.15; 95% CI, 3.10–5.57) was also higher in cytology-positive patients [267]. The positivity rate of peritoneal washing cytology varies from 7% to 58% [259 260 261 263 264 265 267]; this range may be due to differences in the study populations, including early gastric cancer patients. The diverse pathologic criteria of positive cancer cells could also contribute to the wide range of positivity. Although most of the studies did not address the pathologic criteria for ‘positive’ cancer cells in peritoneal washing cytology, there is a need for further studies to establish these pathologic criteria for the clinical application of peritoneal washing cytology in advanced gastric cancer patients. In conclusion, peritoneal washing cytology is recommended for accurate staging and prognosis for advanced gastric cancer even though there remain several controversies. MULTIDISCIPLINARY TEAM (MDT)APPROACH The effectiveness of MDTs in cancer treatment has been controversial because there was no strong evidence and MDT also requires significant time and resources [269 270]. However, MDT has been important for the treatment of cancer because treatment methods are diverse, complex, and specialized. The advantages of MDT include correct diagnosis, changing to a better treatment plan, and survival benefit. For these reasons, health services in several countries have produced guidelines citing MDTs as the preferred system for cancer treatment [271]. Several studies have shown the advantages of MDT in gastrointestinal malignancy. After MDT meetings, changes in diagnosis occurred in 18.4%–26.9% of evaluated patients [272 273], and the treatment plan was changed in 23.0%–76.8% of cancer patients [273 274 275]. Furthermore, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guideline emphasizes the recommendation for MDT and the European Society for Medical Oncology and European Cancer Organization guidelines indicate that MDT before determining cancer treatment is mandatory [61 62 276]. The many types of MDT include conferences the without patient present, face-to-face with the patient, and telemedicine. There is no strong evidence regarding which type is better, although Kunkler et al. [277] reported no difference between telemedicine and face-to-face medicine. In addition, Allum et al. [61] recommended that MDTs should discuss treatment decisions with patients. The MDT members for gastric cancer treatment are recommended to include surgeons, gastroenterologist, medical and radiation oncologists, radiologists and pathologists, and other members such as those from nutritional services, social workers, nurses, and palliative care specialists [62 276 278 279]. In conclusion, MDT treatment has a benefit in the treatment of gastric cancer patients regarding patient satisfaction, change to better treatment plans, and more correct diagnosis; however, stronger evidence is required. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Members of the Guideline Committee Development Working Group Korean Gastric Cancer Association: Keun Won Ryu (National Cancer Center), Young Suk Park (Seoul National University Bundang Hospital), Oh Kyoung Kwon (Kyungpook National University Chilgok Hospital), Jeong Oh (Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital), Han Hong Lee (The Catholic University of Korea Seoul St. Mary's Hospital), Seong Ho Kong (Seoul National University Hospital), Taeil Son (Severance Hospital), Hoon Hur (Ajou University Hospital), Ye Seob Jee (Dankook University Hospital), Hong Man Yoon (National Cancer Center); Korean Society of Gastroenterology: Changyoo Kim (National Cancer Center), Byung-Hoon Min (Samsung Medical Center), Ho-june Song (Asan Medical Center), Woon Geon Shin (Kangdong Sacred Heart Hospital), Sang Kil Lee (Severance Hospital), Jae-Young Jang (Kyung Hee University Hospital), Hye-kyung Jung (Ewha Womans University Mokdong Hospital); Korean Society of Medical Oncology: Min-Hee Ryu (Asan Medical Center), Sun Jin Sym (Gachon University Gil Medical Center), Sangcheul Oh (Korea University Guro Hospital), Byoung Yong Shim (Catholic University of Korea St. Vincent's Hospital), Dae Young Zang (Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital), Hye Sook Han (Chungbuk National University Hospital), Dong-Hoe Koo (Kangbuk Samsung Hospital), Hyeong Su Kim (Hallym University Kangnam Sacred Heart Hospital), Chi Hoon Maeng (Kyung Hee University Hospital), In Gyu Hwang (Chung-Ang University Hospital); Korean Society for Radiation Oncology: Jeong Il Yu (Samsung Medical Center), Eui Kyu Chie (Seoul National University Hospital); Korean Society of Pathologists: Joon Mee Kim (Inha University Hospital), Baek-Hui Kim (Korea University Guro Hospital), Myeong-Cherl Kook (National Cancer Center), Hye Seung Lee (Seoul National University Bundang Hospital); National Evidence-Based Healthcare Collaboration Agency: Miyoung Choi. Review Panel Korean Gastric Cancer Association: Chan-Young Kim (Chonbuk National University Hospital), Sungho Jin (Korea Institute of Radiological and Medical Sciences); Korean Society of Gastroenterology: Jae Myung Park (Seoul St. Mary's Hospital), Cheol Min Shin (Seoul National University Bundang Hospital); Korean Society of Medical Oncology: Do-Youn Oh (Seoul National University Hospital), Keun-Wook Lee (Seoul National University Bundang Hospital); Korean Society for Radiation Oncology: Tae-Hyun Kim (National Cancer Center); Korean Society of Pathologists: Kyoung-Mee Kim (Samsung Medical Center).