- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

An international RAND/UCLA expert panel to determine the optimal diagnosis and management of burn inhalation injury

Read this article at

Abstract

Background

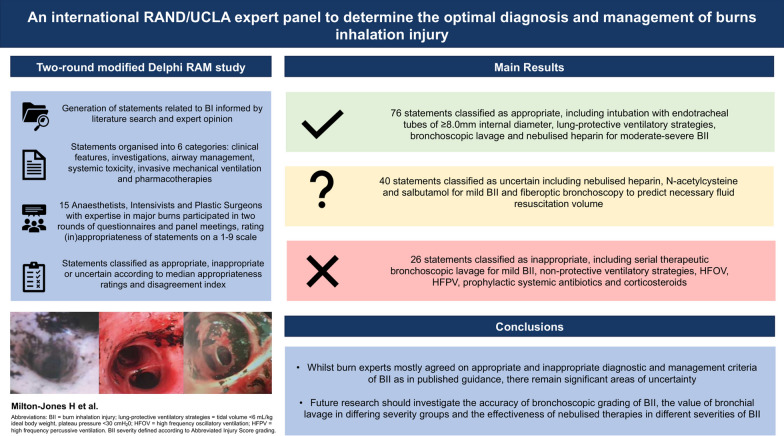

Burn inhalation injury (BII) is a major cause of burn-related mortality and morbidity. Despite published practice guidelines, no consensus exists for the best strategies regarding diagnosis and management of BII. A modified DELPHI study using the RAND/UCLA (University of California, Los Angeles) Appropriateness Method (RAM) systematically analysed the opinions of an expert panel. Expert opinion was combined with available evidence to determine what constitutes appropriate and inappropriate judgement in the diagnosis and management of BII.

Methods

A 15-person multidisciplinary panel comprised anaesthetists, intensivists and plastic surgeons involved in the clinical management of major burn patients adopted a modified Delphi approach using the RAM method. They rated the appropriateness of statements describing diagnostic and management options for BII on a Likert scale. A modified final survey comprising 140 statements was completed, subdivided into history and physical examination (20), investigations (39), airway management (5), systemic toxicity (23), invasive mechanical ventilation (29) and pharmacotherapy (24). Median appropriateness ratings and the disagreement index (DI) were calculated to classify statements as appropriate, uncertain, or inappropriate.

Results

Of 140 statements, 74 were rated as appropriate, 40 as uncertain and 26 as inappropriate. Initial intubation with ≥ 8.0 mm endotracheal tubes, lung protective ventilatory strategies, initial bronchoscopic lavage, serial bronchoscopic lavage for severe BII, nebulised heparin and salbutamol administration for moderate-severe BII and N-acetylcysteine for moderate BII were rated appropriate. Non-protective ventilatory strategies, high-frequency oscillatory ventilation, high-frequency percussive ventilation, prophylactic systemic antibiotics and corticosteroids were rated inappropriate. Experts disagreed (DI ≥ 1) on six statements, classified uncertain: the use of flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy to guide fluid requirements (DI = 1.52), intubation with endotracheal tubes of internal diameter < 8.0 mm (DI = 1.19), use of airway pressure release ventilation modality (DI = 1.19) and nebulised 5000IU heparin, N-acetylcysteine and salbutamol for mild BII (DI = 1.52, 1.70, 1.36, respectively).

Conclusions

Burns experts mostly agreed on appropriate and inappropriate diagnostic and management criteria of BII as in published guidance. Uncertainty exists as to the optimal diagnosis and management of differing grades of severity of BII. Future research should investigate the accuracy of bronchoscopic grading of BII, the value of bronchial lavage in differing severity groups and the effectiveness of nebulised therapies in different severities of BII.

Related collections

Most cited references39

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network.

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

High-frequency oscillation in early acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Author and article information

Comments

Comment on this article

Smart Citations

Smart CitationsSee how this article has been cited at scite.ai

scite shows how a scientific paper has been cited by providing the context of the citation, a classification describing whether it supports, mentions, or contrasts the cited claim, and a label indicating in which section the citation was made.