- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Incidence and Trends of Infection with Pathogens Transmitted Commonly Through Food — Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network, 10 U.S. Sites, 2006–2013

research-article

Stacy M. Crim , MPH

1 ,

Martha Iwamoto , MD

1 ,

Jennifer Y. Huang , MPH

1 ,

Patricia M. Griffin , MD

1 ,

Debra Gilliss , MD

2 ,

Alicia B. Cronquist , MPH

3 ,

Matthew Cartter , MD

4 ,

Melissa Tobin-D’Angelo , MD

5 ,

David Blythe , MD

6 ,

Kirk Smith , DVM

7 ,

Sarah Lathrop , PhD

8 ,

Shelley Zansky , PhD

9 ,

Paul R. Cieslak , MD

10 ,

John Dunn , DVM

11 ,

Kristin G. Holt , DVM

12 ,

Susan Lance , DVM

13 ,

Robert Tauxe , MD

1 ,

Olga L. Henao , PhD

1

18 April 2014

Read this article at

There is no author summary for this article yet. Authors can add summaries to their articles on ScienceOpen to make them more accessible to a non-specialist audience.

Abstract

Foodborne disease continues to be an important problem in the United States. Most

illnesses are preventable. To evaluate progress toward prevention, the Foodborne Diseases

Active Surveillance Network* (FoodNet) monitors the incidence of laboratory-confirmed

infections caused by nine pathogens transmitted commonly through food in 10 U.S. sites,

covering approximately 15% of the U.S. population. This report summarizes preliminary

2013 data and describes trends since 2006. In 2013, a total of 19,056 infections,

4,200 hospitalizations, and 80 deaths were reported. For most infections, incidence

was well above national Healthy People 2020 incidence targets and highest among children

aged <5 years. Compared with 2010–2012, the estimated incidence of infection in 2013

was lower for Salmonella, higher for Vibrio, and unchanged overall.† Since 2006–2008,

the overall incidence has not changed significantly. More needs to be done. Reducing

these infections requires actions targeted to sources and pathogens, such as continued

use of Salmonella poultry performance standards and actions mandated by the Food Safety

Modernization Act (FSMA) (1). FoodNet provides federal and state public health and

regulatory agencies as well as the food industry with important information needed

to determine if regulations, guidelines, and safety practices applied across the farm-to-table

continuum are working.

FoodNet conducts active, population-based surveillance for laboratory-confirmed infections

caused by Campylobacter, Cryptosporidium, Cyclospora, Listeria, Salmonella, Shiga

toxin–producing Escherichia coli (STEC) O157 and non-O157, Shigella, Vibrio, and Yersinia

in 10 sites covering approximately 15% of the U.S. population (an estimated 48 million

persons in 2012).§ FoodNet is a collaboration among CDC, 10 state health departments,

the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (USDA-FSIS),

and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Hospitalizations occurring within 7 days

of specimen collection are recorded, as is the patient’s vital status at hospital

discharge, or at 7 days after specimen collection if the patient was not hospitalized.

Hospitalizations and deaths that occur within 7 days are attributed to the infection.

Surveillance for physician-diagnosed postdiarrheal hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS),

a complication of STEC infection characterized by renal failure, is conducted through

a network of nephrologists and infection preventionists and by hospital discharge

data review. This report includes 2012 HUS data for persons aged <18 years.

Incidence was calculated by dividing the number of laboratory-confirmed infections

in 2013 by U.S. Census estimates of the surveillance area population for 2012.¶ Incidence

of culture-confirmed bacterial infections and laboratory-confirmed parasitic infections

(e.g., identified by enzyme immunoassay) are reported. A negative binomial model with

95% confidence intervals (CIs) was used to estimate changes in incidence from 2010–2012

to 2013 and from 2006–2008 to 2013 (2). Change in the overall incidence of infection

with six key foodborne pathogens was estimated (3). For STEC non-O157, only change

since 2010–2012 was assessed because diagnostic practices changed before then; for

Cyclospora, change was not assessed because data were sparse. For HUS, incidence was

compared with 2006–2008. The number of reports of positive culture-independent diagnostic

tests (CIDTs) without corresponding culture confirmation is included for Campylobacter,

Listeria, Salmonella, Shigella, STEC, Vibrio, and Yersinia.

Cases of Infection, Incidence, and Trends

In 2013, FoodNet identified 19,056 cases of infection, 4,200 hospitalizations, and

80 deaths (Table). The number and incidence per 100,000 population were Salmonella

(7,277 [15.19]), Campylobacter (6,621 [13.82]), Shigella (2,309 [4.82]), Cryptosporidium

(1,186 [2.48]), STEC non-O157 (561 [1.17]), STEC O157 (552 [1.15]), Vibrio (242 [0.51]),

Yersinia (171 [0.36]), Listeria (123 [0.26]), and Cyclospora (14 [0.03]). Incidence

was highest among persons aged ≥65 years for Cyclospora, Listeria, and Vibrio and

among children aged <5 years for all the other pathogens.

Among 6,520 (90%) serotyped Salmonella isolates, the top serotypes were Enteritidis,

1,237 (19%); Typhimurium, 917 (14%); and Newport, 674 (10%). Among 231 (95%) speciated

Vibrio isolates, 144 (62%) were V. parahaemolyticus, 27 (12%) were V. alginolyticus,

and 21 (9%) were V. vulnificus. Among 458 (82%) serogrouped STEC non-O157 isolates,

the top serogroups were O26 (34%), O103 (25%), and O111 (14%).

Compared with 2010–2012, the 2013 incidence was significantly lower for Salmonella

(9% decrease; CI = 3%–15%), higher for Vibrio (32% increase; CI = 8%–61%) and not

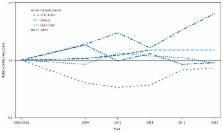

significantly changed for other pathogens (Figure 1). Compared with 2006–2008, the

2013 incidence was significantly higher for Campylobacter and Vibrio (Figure 2). The

overall incidence of infection with six key foodborne pathogens was not significantly

different in 2013 compared with 2010–2012 or 2006–2008.

Compared with 2010–2012, the 2013 incidence of infection with specific Salmonella

serotypes was significantly lower for Enteritidis (14% decrease; CI = 0.2%–25%) and

Newport (32% decrease; CI = 17%–44%) and not significantly changed for Typhimurium.

Compared with 2006–2008, however, the 2013 incidence of infection was significantly

changed only for Typhimurium (20% decrease; CI = 10%–28%).

Among 62 cases of postdiarrheal HUS in children aged <18 years (0.56 cases per 100,000)

in 2012, 38 (61%) occurred in children aged <5 years (1.27 cases per 100,000). Compared

with 2006–2008, the incidence was significantly lower for children aged <5 years (36%

decrease; CI = 9%–55%) and for children aged <18 years (31% decrease; CI = 7%–49%).

In addition to culture-confirmed infections (some with a positive CIDT result), there

were 1,487 reports of positive CIDTs that were not confirmed by culture, either because

the specimen was not cultured at either the clinical or public health laboratory or

because a culture did not yield the pathogen. For 1,017 Campylobacter reports in this

category, 430 (42%) had no culture, and 587 (58%) were culture-negative. For 247 STEC

reports, 59 (24%) had no culture, and 188 (76%) were culture-negative. The Shiga toxin–positive

result was confirmed for 65 (34%) of 192 broths sent to a public health laboratory.

The other reports of positive CIDT tests not confirmed by culture were of Shigella

(147), Salmonella (69), Vibrio (four), Listeria (two), and Yersinia (one).

Discussion

The incidence of laboratory-confirmed Salmonella infections was lower in 2013 than

2010–2012, whereas the incidence of Vibrio infections increased. No changes were observed

for infection with Campylobacter, Listeria, STEC O157, or Yersinia, the other pathogens

transmitted commonly through food for which Healthy People 2020 targets exist. The

lack of recent progress toward these targets points to gaps in the current food safety

system and the need for more food safety interventions.

Although the incidence of Salmonella infection in 2013 was lower than during 2010–2012,

it was similar to 2006–2008, well above the national Healthy People target. Salmonella

organisms live in the intestines of many animals and can be transmitted to humans

through contaminated food or water or through direct contact with animals or their

environments; different serotypes can have different reservoirs and sources. Enteritidis,

the most commonly isolated serotype, is often associated with eggs and poultry. The

incidence of Enteritidis infection was lower in 2013 compared with 2010–2012, but

not compared with 2006–2008. This might be partly explained by the large Enteritidis

outbreak linked to eggs in 2010.** Ongoing efforts to reduce contamination of eggs

include FDA’s Egg Safety Rule, which requires shell egg producers to implement controls

to prevent contamination of eggs on the farm and during storage and transportation.††

FDA required compliance by all egg producers with ≥50,000 laying hens by 2010 and

by producers with ≥3,000 hens by 2012. Reduction in Enteritidis infection has been

one of five high-priority goals for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

since 2012.§§

In 2013, the incidence of Vibrio infections was the highest observed in FoodNet to

date, though still much lower than that of Salmonella or Campylobacter. Vibrio infections

are most common during warmer months, when waters contain more Vibrio organisms. Many

infections follow contact with seawater (4), but about 50% of domestically acquired

infections are transmitted through food, most commonly oysters (5). Foodborne infections

can be prevented by postharvest treatment of oysters with heat, freezing, or high

pressure, by thorough cooking, or by not eating oysters during warmer months (6).

During the summers of 2012 and 2013, many V. parahaemolyticus infections of a strain

previously traced only to the Pacific Northwest were associated with consumption of

oysters and other shellfish from several Atlantic Coast harvest areas.¶¶

V. alginolyticus, the second most common Vibrio reported to FoodNet in 2013, typically

causes wound and soft-tissue infections among persons who have contact with water

(7).

The continued decrease in the incidence of postdiarrheal HUS has not been matched

by a decline in STEC O157 infections. Possible explanations include unrecognized changes

in surveillance, improvements in management of STEC O157 diarrhea, or an actual decrease

in infections with the most virulent strains of STEC O157. It is possible that more

stool specimens are being tested for STEC, resulting in increased detection of milder

infections than in the past. Continued surveillance is needed to determine if this

pattern holds.

CIDTs are increasingly used by clinical laboratories to diagnose bacterial enteric

infections, a trend that will challenge the ability to identify cases, monitor trends,

detect outbreaks, and characterize pathogens (8). Therefore, FoodNet began tracking

CIDT-positive reports and surveying clinical laboratories about their diagnostic practices.

The adoption of CIDTs has varied by pathogen and has been highest for STEC and Campylobacter.

Positive CIDTs frequently cannot be confirmed by culture, and the positive predictive

value varies by the CIDT used. For STEC, most specimens identified as Shiga toxin–positive

were sent to a public health laboratory for confirmation. However, for other pathogens

the fraction of specimens from patients with a positive CIDT sent for confirmation

likely is low because no national guidelines regarding confirmation of CIDT results

currently exist. As the number of approved CIDTs increases, their use likely will

increase rapidly. Clinicians, clinical and public health laboratorians, public health

practitioners, regulatory agencies, and industry must work together to maintain strong

surveillance to detect dispersed outbreaks, measure the impact of prevention measures,

and identify emerging threats.

The findings in this report are subject to at least five limitations. First, health-care–seeking

behaviors and other characteristics of the population in the surveillance area might

affect the generalizability of the findings. Second, some agents transmitted commonly

through food (e.g., norovirus) are not monitored by FoodNet because clinical laboratories

do not routinely test for them. Third, the proportion of illnesses transmitted by

nonfood routes differs by pathogen; data provided in this report are not limited to

infections from food. Fourth, in some fatal cases, infection with the enteric pathogen

might not have been the primary cause of death. Finally, changes in incidence between

periods can reflect year-to-year variation during those periods rather than sustained

trends.

Most foodborne illnesses can be prevented, and progress has been made in decreasing

contamination of some foods and reducing illness caused by some pathogens since 1996,

when FoodNet began. More can be done; surveillance data provide information on where

to target prevention efforts. In 2011, USDA-FSIS tightened its performance standard

for Salmonella contamination of whole broiler chickens; in 2013, 3.9% of samples tested

positive (Christopher Aston, USDA-FSIS, Office of Data Integration and Food Protection;

personal communication; 2014). Because most chicken is purchased as cut-up parts,

USDA-FSIS conducted a nationwide survey of raw chicken parts in 2012 and calculated

an estimated 24% prevalence of Salmonella (9). In 2013, USDA-FSIS released its Salmonella

Action Plan that indicates that USDA-FSIS will conduct a risk assessment and develop

performance standards for poultry parts during 2014, among other key activities (10).

The Food Safety Modernization Act of 2011 gives FDA additional authority to regulate

food facilities, establish standards for safe produce, recall contaminated foods,

and oversee imported foods; it also calls on CDC to strengthen surveillance and outbreak

response (1). For consumers, advice on safely buying, preparing, and storing foods

prone to contamination is available online.

What is already known on this topic?

The incidences of infection caused by Campylobacter, Salmonella, Shiga toxin–producing

Escherichia coli O157, and Vibrio are well above their respective Healthy People 2020

targets. Foodborne illness continues to be an important public health problem.

What is added by this report?

In 2013, a total of 19,056 infections, 4,200 hospitalizations, and 80 deaths were

reported to the Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet). For most

infections, incidence was highest among children aged <5 years. In 2013, compared

with 2010–2012, the estimated incidence of infection was unchanged overall, lower

for Salmonella, and higher for Vibrio infections, which have been increasing in frequency

for many years. The number of patients being diagnosed by culture-independent diagnostic

tests (CIDT) is increasing.

What are the implications for public health practice?

Reducing the incidence of foodborne infections requires greater commitment and more

action to implement measures to reduce contamination of food. Monitoring the incidence

of these infections is becoming more difficult because some laboratories are now using

CIDTs, and some do not follow up a positive CIDT result with a culture.

Related collections

Most cited references5

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Nonfoodborne Vibrio infections: an important cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States, 1997-2006.

Ite Yu, John Painter, Amy M Dechet … (2008)

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

The role of Gulf Coast oysters harvested in warmer months in Vibrio vulnificus infections in the United States, 1988-1996. Vibrio Working Group.

Douglas Kernodle, Brian P. Griffin, Ratna B. Ray … (1998)

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Methods for monitoring trends in the incidence of foodborne diseases: Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network 1996-2008.

Olga L. Henao, R. M. Hoekstra, Barbara Mahon … (2010)