- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Measles-Rubella Supplementary Immunization Activity Readiness Assessment — India, 2017–2018

research-article

Vandana Gurnani , MA

1 ,

Pradeep Haldar , MD

1 ,

Sudhir Khanal , MBBS

2

,

,

Pankaj Bhatnagar , MD

3 ,

Balwinder Singh , MBBS

3 ,

Danish Ahmed , MBBS

3 ,

Mohammad Samiuddin , MBBS

3 ,

Arun Kumar , MSc

3 ,

Yashika Negi , MD

1 ,

Satish Gupta , MD

4 ,

Pauline Harvey , PhD

3 ,

Sunil Bahl , MD

2 ,

Alya Dabbagh , PhD

5 ,

James P. Alexander , MD

6 ,

James L. Goodson , MPH

6

06 July 2018

Read this article at

There is no author summary for this article yet. Authors can add summaries to their articles on ScienceOpen to make them more accessible to a non-specialist audience.

Abstract

In 2013, during the 66th session of the Regional Committee of the World Health Organization

(WHO) South-East Asia Region (SEAR), the 11 SEAR countries* adopted goals to eliminate

measles and control rubella and congenital rubella syndrome by 2020

†

(

1

). To accelerate progress in India (

2

,

3

), a phased

§

nationwide supplementary immunization activity (SIA)

¶

using measles-rubella vaccine and targeting approximately 410 million children aged

9 months–14 years commenced in 2017 and will be completed by first quarter of 2019.

To ensure a high-quality SIA, planning and preparation were monitored using a readiness

assessment tool adapted from the WHO global field guide** (

4

) by the India Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. This report describes the results

and experience gained from conducting SIA readiness assessments in 24 districts of

three Indian states (Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, and Telangana) during the second phase

of the SIA. In each selected area, assessments were conducted 4–6 weeks and 1–2 weeks

before the scheduled SIA. At the first assessment, none of the states and districts

were on track with preparations for the SIA. However, at the second assessment, two

(67%) states and 21 (88%) districts were on track. The SIA readiness assessment identified

several preparedness gaps; early assessment results were immediately communicated

to authorities and led to necessary corrective actions to ensure high-quality SIA

implementation.

Supplemental Immunization Activity Readiness Assessment Process

SIA readiness assessments were conducted in 24 (41%) of the 58 districts in the states

of Andhra Pradesh (seven districts), Kerala (five), and Telangana (12). In addition,

74 (72%) of 103 blocks

††

in Telangana were selected for readiness assessments. Districts and blocks were selected

for assessment based on low routine vaccination coverage, difficult-to-reach populations,

high proportion of urban to rural population, and categorization as polio high-risk

based on polio risk assessments.

The assessments were conducted by teams coordinated by the WHO India Country Office.

The teams included members from the India Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, especially

the Immunization Technical Support Unit, National Institute of Health and Family Welfare,

and senior immunization program officers from other states; United Nations agencies,

including WHO, United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), and United Nations Development

Program; and nongovernmental organizations, including John Snow Inc., Global Health

Strategies, CORE Group Polio Project, and others.

The India SIA readiness assessment tool and checklists were adapted from the WHO field

guide for planning and implementing SIAs (

4

) according to the India national measles-rubella SIA operational guidelines, for

use at the national, state, district, and block levels. Assessment teams reviewed

preparations in planning and coordination, advocacy, accountability, management of

adverse events following immunization, vaccines and logistics management, funding,

and communication, using checklists modified at each level based on expected functions

of SIA components for that level (Table 1). The checklists included questions with

possible answers of “yes” or “no.” The overall percentage of affirmative responses

was calculated, and the assessed area was categorized as “on track” (≥80%), “needs

work” (60%–79%), or “not ready” (<60%).

TABLE 1

Questions on supplementary immunization activities readiness assessment checklist,

by component — India, 2017–2018

Component

Activity

Planning and coordination

State/District SIA Steering Committee met at least once?

Did all essential government officials participate in at least one State Task Force

for Immunization (STFI) meeting?*

Circle those who did not participate: Permanent Secretary/State Education Officer/State

Program Officer/Women and Child Development/Integrated Child Development Services/Minority

Welfare Officer*

Did essential non-governmental stakeholders participate in at least one STFI meeting?*

Circle those who did not participate: Indian Medical Association (IMA)/Indian Academy

of Pediatrics (IAP)/private practitioners/LIONS International/religious leaders.*

State/district Immunization Officer or other state level monitors using state checklist-A

for tracking progress of state level preparedness?

State/district Immunization Officer using checklist-B for tracking progress by visiting

the priority districts?*

State/district monitors identified for visiting the priority districts for assessing

the SIA preparedness?

State/district Education Officer communicated with all District Education Officer?

State/district Program Officer communicated with all Child Development Project Officers?

Has the state committee for adverse events following immunization (AEFI) met at least

once?

Sensitization meetings

Sensitization meeting held with heads of IMA and IAP, including leading private practitioners?*

Sensitization meeting held with district level Education Officers?

Coordination meeting with state level representatives of public schools, private schools’

associations, religious institutions, etc.?*

Vaccine logistics and management

Adequate quantity of vaccine and diluents available per microplan? (consider planned

staggered distribution of vaccine)

Adequate quantity of auto-disable syringes and mixing syringes available per microplan?

(consider planned staggered distribution of vaccine)

Adequate quantity of indelible marker pens available per microplan? Vaccine distribution

plan available for districts?

Funds

Has state received funds from the national level?

Has state disseminated financial guidelines to all districts?

Communication planning

Is there a nodal officer, other than State EPI Officer, designated for SIA communication

planning at state level?

At least one joint meeting held for secretaries of Health, Education, other department?

(check for official circular)

State communication core group formed and held at least one meeting? (verify meeting

minutes)*

SIA communication plan prepared in a template as per operational guidelines?

All districts/blocks have submitted communication plan in prescribed template?

Received guidelines for communication activities including financial for SIA and shared

with all districts? (check for official circular)*

State/district implementing communication plan for underserved communities? (identified

influencers, religious and educational institutions for support)*

Was there discussion on communication planning in STFI? (verify meeting minutes)

Communication and social mobilization

Printed and distributed all IEC (Information, Education, and Communication) materials

or guidelines?

Identified local celebrities or champion for SIA? (verify how involved in SIA)

State/district launch or inauguration for SIA? (confirm date for launch)

Advocacy

Sensitization meeting with religious leaders or influencers planned/held?

Media and social media

State/district has identified media spokesperson for the SIA?

Media workshop planned at state level for SIA? (confirm dates for media workshop)

Is an official or agency regularly tracking media and social media for SIA and immunization

messages? (collect related news articles)*

Task force for social media was formed? (confirm at least one responsible person designated

at state level for managing social media)

WhatsApp group(s) was formed for health, education, and immunization-related sectors?

Facebook page was created for the SIA? (check the page for SIA post)*

* These variables were considered to be critical and were evaluated subjectively by

the assessment team to decide "go" or "delayed go" for an area marked as "needs work."

The checklists used at state, district, planning unit, and school levels were modified

to reflect the level-specific role and function for each component.

The first readiness assessment was conducted 4–6 weeks before the SIA and the second,

1–2 weeks before the SIA. A decision either to start the SIA on the designated date

or to delay the SIA until preparations were complete was made at the district and

state levels, based on the second assessment score and categorization of the district

or state assessed. Those areas categorized as on track were permitted to start the

SIA (“go”); those categorized as not ready were delayed (“delayed go”); and those

categorized as needing work either started or delayed the SIA, based on subjective

evaluation by the assessment team of critical gaps and level of commitment to taking

corrective actions in a timely manner. At the end of the assessment, evidence-based

feedback from the teams was shared with health and administration leaders at district,

state, and national levels to facilitate decision-making for strengthening the quality

of this and future SIAs.

Supplemental Immunization Activity Readiness Assessment Results

At the first assessment, none of the three states and none of the 24 districts was

on track (Table 2). The challenges most frequently identified during the preparedness

assessment were lack of logistics and training materials and nonengagement of schools.

Based on feedback provided, state-level program managers initiated corrective actions

in all districts. At the second assessment, Kerala and Telangana states were on track;

Andhra Pradesh needed work and had to delay the start of the SIA to provide an additional

week for preparation. Overall, 19 (79%) of the 24 districts were on track (including

information, education, and communication [IEC] readiness), four (17%) needed additional

work and undertook minor corrective actions, and one (4%) was not ready and had a

delayed go.

TABLE 2

Supplementary immunization activity readiness assessment* results — three states,

India, 2017–2018

SIA readiness assessment results

State (no. of districts)

Andhra Pradesh (7)

Kerala (5)

Telangana (12)

First assessment

Not ready, no. (%)

5 (71)

1 (20)

10 (83)

Needs work, no. (%)

2 (29)

4 (80)

2 (17)

On track, no. (%)

0 (0)

0 (0)

0 (0)

Key findings

State level trainings not started

No SIA logistics plan available

IEC materials not available

IEC materials not available

No schools aware of SIA

No clarity on SIA financial guidelines

Most schools not informed

Trainings conducted without training materials

Private schools not on board

Medical fraternity not involved and informed about SIA

High level of vaccine hesitancy and frank refusal in one district

Informal educational institutions, religious schools, madrasas not in target population

Low level SIA awareness

No clarity on financial guidelines for local implementers

Low level preparedness for management of AEFI

Language barriers

Lack of SIA awareness

Vaccine hesitancy in minority communities

Actions taken

Video conference with all districts by the principal secretary and by each district

to all blocks to discuss assessment findings and plan corrective actions

SIA logistics made immediately available to the districts

Video conference with all deputy commissioners, chief medical officers, and district

immunization officers requesting immediate corrective actions

Principal secretary visited all high-risk districts to get firsthand information on

preparedness progress and next steps

Microplans reviewed in all areas; additional field monitors deployed in high-risk

districts and blocks

Meeting with district education officers to develop plan; directives for noncompliant

schools, meeting with heads of madrasas organized to encourage SIA participation

Operational communication plan developed with all partners; all district microplans

reviewed

Additional communication and social mobilization officers mobilized in areas with

vaccine hesitancy and refusal

Prominent talk show personalities appear on local television channels; media release

in Urdu language; video of prominent opinion leaders and religious leaders developed

and circulated through social media platform

Medical and Indian Academy of Pediatrics invited to participate in process and promote

SIA in local newspaper

Medical colleges and medical fraternity brought on board as support group to the SIA

District magistrates briefed on assessment results; called all immunization offices

and received regular updates on progress to accelerate preparedness

Senior state officers visited high-risk areas to accelerate preparedness activities

District AEFI committee reactivated and capacity building done

Administrative processes to print and deploy materials were fast-tracked. Orientation

on financial guidelines

Meeting with district governors of Lions Clubs International and request to adopt

problematic schools to accelerate SIA preparedness and awareness

Second assessment

Not ready, no. (%)

1 (14)

0 (0)

0 (0)

Needs work, no. (%)

3 (43)

0 (0)

1 (8)

On track, no. (%)

3 (43)

5 (100)

11 (92)

Decision

Delay

Move forward

Move forward

% Administrative coverage, state (districts range)

97 (86 to >100)

89 (87 to 98)

>100 (87 to >100)

Abbreviations: AEFI = adverse events following immunization; IEC = information, education,

and communication; SIA = supplementary immunization activity.

* SIA readiness assessments during planning for phase 2 of the nationwide SIA using

measles-rubella vaccine for children aged 9 months–14 years that started in 2017.

The first readiness assessment was conducted at 4–6 weeks before the SIA and the second

assessment at 1–2 weeks before the SIA. Checklists had questions with possible answers

of “Yes” or “No.” Scoring was based on percentage of “Yes” responses, categorized

as on track (≥80%), needs work (60%–79%), and not ready (<60%). Administrative coverage

>100% indicated the intervention reached more persons than were in the estimated target

population.

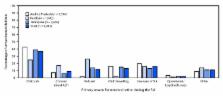

During the SIA, rapid convenience monitoring, a programmatic tool that identifies

children not vaccinated during the campaign and compiles reasons for nonvaccination,

determined that 9,912 (6.9%) of all 143,894 targeted children were not vaccinated

during the SIA, including 7% (3,314 of 44,906) in Andhra Pradesh, 10% (1,943 of 19,408)

in Kerala, and 6% (4,659 of 79,580) in Telangana (Figure). Among all unvaccinated

children located through rapid convenience monitoring, the most frequently reported

reason given by caregivers for not vaccinating was that the child was sick (3,715;

37%), followed by lack of awareness of the campaign (1,566; 16%). In Kerala, refusal

accounted for approximately a quarter of children who were not vaccinated. The least

frequently reported reason (209; 2%) for nonvaccination was SIA operational gaps (e.g.,

nonfunctioning vaccination sites, absent or late vaccinators, vaccine stock-outs,

and other logistics issues) (Figure). Reported SIA administrative coverage was ≥95%

in two states and 17 districts (Table 2).

FIGURE

Percentage of unvaccinated children, by reported primary reason for nonvaccination*

during supplementary immunization activity

†

(phase 2)

§

— Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, and Telangana states, India, 2017–2018

Abbreviations: AEFI = Adverse events following immunization; MR = measles-rubella;

SIA = supplementary immunization activity.

* Intra-SIA monitoring using rapid convenience monitoring.

† Nationwide SIA using MR vaccine for children aged 9 months–14 years.

§ Phase 2 of phased nationwide SIA started in 2017 and to be completed by first quarter

of 2019. Children targeted for vaccination during phase 2 of the SIA but not vaccinated

included 7% in Andhra Pradesh, 10% in Kerala, and 6% in Telangana.

The figure above is a bar chart showing the percentage of unvaccinated children, by

reported primary reason for nonvaccination, during phase 2 of a supplementary immunization

activity in the states of Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, and Telangana in India during 2017–2018.

Discussion

Experience with the SIA assessment in India demonstrated that the WHO SIA readiness

assessment tool and procedures were useful for ensuring preparedness for implementation

of a high-quality SIA. Corrective actions implemented after the first assessment,

which found that two thirds of districts were not ready for the SIA, resulted in 79%

of districts being on track by the second assessment. Providing feedback to key decision-makers

immediately after the assessments helped with planning and allocation of resources

and facilitated implementation of timely corrections. These midcourse corrections

also might have resulted in further-reaching effects across each of the three states

because of the statewide directives issued by immunization program managers for corrective

actions in all districts to better prepare for this SIA and future SIAs.

As suggested in the global guidelines, decision-makers in India used the terminology

“delayed go” rather than “no go” in states and districts assessed as not ready for

the measles-rubella SIA, to provide positive reinforcement to immunization program

personnel who needed additional time for preparation. Intra-SIA rapid convenience

monitoring found that SIA operational gaps were the least common reason for children

not being vaccinated, an indication of good preparation and implementation of campaign

activities. The primary reasons for children not being vaccinated during the SIA were

related to IEC gaps and challenges in addressing parental misperceptions and their

lack of awareness of and availability for the SIA. These findings suggest that the

WHO SIA readiness checklists section on IEC and communication strategies might need

to be revised and expanded.

Although WHO global guidance recommends four to six assessments before an SIA to ensure

readiness, in this setting, only two pre-SIA assessments were designed and conducted

in each area. Because the SIA readiness assessment process was part of the overall

operational activities and covered by the existing technical assistance of WHO, UNICEF,

and partners, no additional costs were budgeted for the activity. However, inclusion

of more districts, blocks, and health centers in the process could help to ensure

homogeneous quality of SIA implementation.

The findings in this report are subject to at least two limitations. First, the selection

of areas for readiness assessments included in this report was purposeful, and no

control groups were available for comparison. Second, the impact of the readiness

assessments on achieving the ≥95% SIA coverage target was not assessed by post-SIA

surveys because of time and resource limitations and lack of a comparison group.

The WHO South-East Asia Region aims to vaccinate >500 million children with measles-rubella

vaccine through SIAs by 2019. The experience with pre-SIA assessments in India reported

here will help improve preparedness for high-quality SIAs, ensuring high vaccination

coverage to achieve the regional goal of measles elimination and rubella and congenital

rubella syndrome control by 2020.

Summary

What is already known about this topic?

India has adopted a goal for measles elimination and rubella and congenital rubella

syndrome control by 2020 by achieving high coverage with 2 routine doses of measles-containing

vaccine and supplemental immunization activities (SIAs), which require substantial

preparation.

What is added by this report?

Two pre-SIA readiness assessments in 24 districts in three states provided feedback

to decision-makers that led to corrective actions. Readiness improved from 33% to

79% between the two assessments.

What are the implications for public health practice?

The WHO South-East Asia Region aims to vaccinate >500 million children with measles-rubella

vaccine through SIAs by 2019. The experience with pre-SIA assessments can help improve

preparedness and ensure high coverage through SIAs in the region.

Related collections

Most cited references1

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Progress Toward Regional Measles Elimination — Worldwide, 2000–2016

Alya Dabbagh, Minal K Patel, Laure Dumolard … (2017)