- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Comparison analysis of different swabs and transport mediums suitable for SARS-CoV-2 testing following shortages

Read this article at

Highlights

-

•

High demand for diagnostic testing for COVID-19 has depleted commercially available consumables for diagnostic testing.

-

•

Alternative swabs that are not approved for Nasopharyngeal sampling work well for COVID-19 diagnostics.

-

•

Alternative fluids that are readily available in hospital settings can function as alternatives to Viral Transport Media.

-

•

No meaningful difference in viral yield from different swabs and most transport mediums for the collection and detection of SARS-CoV-2, indicating swab and medium alternatives could be used if supplies run out.

Abstract

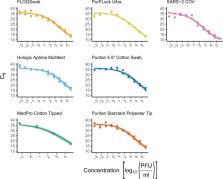

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) assessed COVID-19, caused by SARS-CoV-2, as a pandemic. As of June 1, 2020, SARS-CoV-2 has had a documented effect of over 6 million cases world-wide, amounting to over 370,000 deaths (World Health Organization, 2020. Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Situation. http:// https://covid19.who.int/). Consequently, the high demand for testing has resulted in a depletion of commercially available consumables, including the recommended swabs and viral transport media (VTM) required for nasopharyngeal sampling. Therefore, the potential use of unvalidated alternatives must be explored to address the global shortage of testing supplies. To tackle this issue, we evaluated the utility of different swabs and transport mediums for the molecular detection of SARS-CoV-2. This study compared the performance of six swabs commonly found in primary and tertiary health care settings (PurFlock Ultra, FLOQSwab, Puritan Pur-Wraps cotton tipped applicators, Puritan polyester tipped applicators, MedPro 6” cotton tipped applicators, and HOLOGIC Aptima) for their efficacy in testing for SARS-CoV-2. Separately, the molecular detection of SARS-CoV-2 was completed from different transport mediums (DMEM, PBS, 100 % ethanol, 0.9 % normal saline and VTM), which were kept up to three days at room temperature (RT). The results indicate that there is no meaningful difference in viral yield from different swabs and most transport mediums for the collection and detection of SARS-CoV-2, indicating swab and medium alternatives could be used if supplies run out.

Related collections

Most cited references14

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan, China: The mystery and the miracle

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found