- Record: found

- Abstract: not found

- Article: not found

Rural‐urban differences in monkeypox behaviors and attitudes among men who have sex with men in the United States

Publication date (Electronic):

November 17 2022

Journal:

The Journal of Rural Health

Publisher:

Wiley

Read this article at

There is no author summary for this article yet. Authors can add summaries to their articles on ScienceOpen to make them more accessible to a non-specialist audience.

Related collections

Most cited references45

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

The Health Belief Model: a decade later.

N K Janz, M H Becker (1984)

Since the last comprehensive review in 1974, the Health Belief Model (HBM) has continued to be the focus of considerable theoretical and research attention. This article presents a critical review of 29 HBM-related investigations published during the period of 1974-1984, tabulates the findings from 17 studies conducted prior to 1974, and provides a summary of the total 46 HBM studies (18 prospective, 28 retrospective). Twenty-four studies examined preventive-health behaviors (PHB), 19 explored sick-role behaviors (SRB), and three addressed clinic utilization. A "significance ratio" was constructed which divides the number of positive, statistically-significant findings for an HBM dimension by the total number of studies reporting significance levels for that dimension. Summary results provide substantial empirical support for the HBM, with findings from prospective studies at least as favorable as those obtained from retrospective research. "Perceived barriers" proved to be the most powerful of the HBM dimensions across the various study designs and behaviors. While both were important overall, "perceived susceptibility" was a stronger contributor to understanding PHB than SRB, while the reverse was true for "perceived benefits." "Perceived severity" produced the lowest overall significance ratios; however, while only weakly associated with PHB, this dimension was strongly related to SRB. On the basis of the evidence compiled, it is recommended that consideration of HBM dimensions be a part of health education programming. Suggestions are offered for further research.

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Vaccine confidence in the time of COVID-19

Emily Harrison, Julia W Wu (2020)

In the early months of the COVID-19 epidemic, some have wondered if the force of this global experience will solve the problem of vaccine refusal that has vexed and preoccupied the global public health community for the last several decades. Drawing on historical and epidemiological analyses, we critique contemporary approaches to reducing vaccine hesitancy and articulate our notion of vaccine confidence as an expanded way of conceptualizing the problem and how to respond to it. Intervening on the rush of vaccine optimism we see pervading present discourse around the COVID-19 epidemic, we call for a re-imagination of the culture of public health and the meaning of vaccine safety regulations. Public confidence in vaccination programs depends on the work they do for the community—social, political, and moral as well as biological. The concept of public health and its programs must be broader than the delivery of the vaccine technology itself. The narrative work and policy actions entailed in actualizing such changes will, we expect, be essential in achieving a true vaccine confidence, however the public reacts to the specific vaccine that may be developed for COVID-19.

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

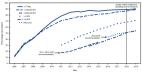

National, Regional, State, and Selected Local Area Vaccination Coverage Among Adolescents Aged 13–17 Years — United States, 2019

Laurie Elam-Evans, David Yankey, James Singleton … (2020)

Three vaccines are recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) for routine vaccination of adolescents aged 11–12 years to protect against 1) pertussis; 2) meningococcal disease caused by types A, C, W, and Y; and 3) human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated cancers ( 1 ). At age 16 years, a booster dose of quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MenACWY) is recommended. Persons aged 16–23 years can receive serogroup B meningococcal vaccine (MenB), if determined to be appropriate through shared clinical decision-making. CDC analyzed data from the 2019 National Immunization Survey-Teen (NIS-Teen) to estimate vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years in the United States.* Coverage with ≥1 dose of HPV vaccine increased from 68.1% in 2018 to 71.5% in 2019, and the percentage of adolescents who were up to date † with the HPV vaccination series (HPV UTD) increased from 51.1% in 2018 to 54.2% in 2019. Both HPV vaccination coverage measures improved among females and males. An increase in adolescent coverage with ≥1 dose of MenACWY (from 86.6% in 2018 to 88.9% in 2019) also was observed. Among adolescents aged 17 years, 53.7% received the booster dose of MenACWY in 2019, not statistically different from 50.8% in 2018; 21.8% received ≥1 dose of MenB, a 4.6 percentage point increase from 17.2% in 2018. Among adolescents living at or above the poverty level, § those living outside a metropolitan statistical area (MSA) ¶ had lower coverage with ≥1 dose of MenACWY and with ≥1 HPV vaccine dose, and a lower percentage were HPV UTD, compared with those living in MSA principal cities. In early 2020, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic changed the way health care providers operate and provide routine and essential services. An examination of Vaccines for Children (VFC) provider ordering data showed that vaccine orders for HPV vaccine; tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap); and MenACWY decreased in mid-March when COVID-19 was declared a national emergency (Supplementary Figure 1, https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/91795). Ensuring that routine immunization services for adolescents are maintained or reinitiated is essential to continuing progress in protecting persons and communities from vaccine-preventable diseases and outbreaks. NIS-Teen is a random-digit-dial telephone survey** conducted annually to monitor vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years in the 50 states, the District of Columbia, selected local areas, and selected U.S. territories. †† Sociodemographic information is collected during the telephone interview with a parent or guardian, and a request is made for consent to contact the adolescent’s vaccination provider(s). If consent is obtained, a questionnaire is mailed to the vaccination provider(s) to request the adolescent’s vaccination history. Vaccination coverage estimates are determined from these provider-reported immunization records. This report provides vaccination coverage estimates on 18,788 adolescents aged 13–17 years. §§ The overall Council of American Survey Research Organizations (CASRO) ¶¶ response rate was 19.7%, and 44.0% of adolescents for whom household interviews were completed had adequate provider data. Data were weighted and analyzed to account for the complex sampling design.*** T-tests were used to assess vaccination coverage differences between sociodemographic subgroups. P-values 20 might not be reliable. § Includes percentages receiving Tdap at age ≥10 years. ¶ Statistically significant difference (p 20 might not be reliable. ¶ Includes percentages receiving Tdap at age ≥10 years. ** Includes percentages receiving MenACWY and meningococcal-unknown type vaccine. †† Statistically significant difference (p<0.05) in estimated vaccination coverage by MSA; referent group was adolescents living in MSA principal city areas. §§ ≥2 doses of MenACWY or meningococcal-unknown type vaccine. Calculated only among adolescents aged 17 years at interview. Does not include adolescents who received 1 dose of MenACWY at age ≥16 years. ¶¶ HPV vaccine, nine-valent (9vHPV), quadrivalent (4vHPV), or bivalent (2vHPV). *** HPV UTD includes those who’ve received ≥3 doses and those with 2 doses when the first HPV vaccine dose was initiated before age 15 years and there was at least 5 months minus 4 days between the first and second dose. This update to the HPV recommendation occurred in December of 2016. ††† In July 2020, ACIP revised recommendations for Hepatitis A vaccination to include catch-up vaccination for children and adolescents aged 2–18 years who have not previously received Hepatitis A vaccine at any age (http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.rr6905a1). §§§ By parent/guardian report or provider records. Trends in HPV Vaccination by Birth Cohort HPV vaccination initiation by age 13 years increased an average of 5.3 percentage points for each consecutive birth year, from 19.9% among adolescents born in 1998 to 62.6% among those born in 2006 (Supplementary Figure 2, https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/91796). Being HPV UTD by age 13 years increased an average of 3.4 percentage points for each consecutive birth year, from 8.0% among adolescents born in 1998 to 35.5% among those born in 2006. Discussion In 2019, coverage with HPV vaccine and with MenACWY improved compared with coverage in 2018. Improvements in ≥1 dose HPV and HPV UTD vaccination coverage were observed among females and males. In addition, more teens began HPV vaccination on time (by age 13 years) in 2019, suggesting that more parents are making the decision to protect their teens against HPV-associated cancers. Efforts from federal, state, and other stakeholders to prioritize HPV vaccination among adolescents, and reducing the number of recommended HPV vaccine doses from a 3-dose to a 2-dose series ( 2 ), likely contributed to these improvements. Coverage with ≥1 dose of MenACWY increased to 88.9%; coverage with ≥2 doses remained low at 53.7%, indicating that continued efforts are needed to improve receipt of the booster dose. Despite progress in adolescent HPV vaccination and MenACWY coverage, disparities remain; all adolescents are not equally protected against vaccine-preventable diseases. As in previous years, compared with adolescents living in MSA principal cities, HPV UTD status and coverage with ≥1 dose each of HPV vaccine and MenACWY continue to be lower among adolescents in non-MSA areas ( 3 ). However, these geographic disparities were present only for adolescents at or above the poverty level in 2019. This finding is consistent with another study that found socioeconomic status to be a moderating factor in the association between HPV vaccination and MSA ( 4 ). The lack of an MSA disparity among adolescents below the poverty level might reflect the access that low-income adolescents have to the VFC program****; previous studies have reported higher HPV vaccination coverage rates among adolescents living below the poverty level ( 5 , 6 ). Reasons for the MSA disparity among higher socioeconomic status adolescents are less clear but might be an indicator of lower vaccine confidence. More work is needed to understand the relationship between socioeconomic status and geographic disparities and the barriers that might be contributing to such differences. The findings in this report are subject to at least two limitations. First, the CASRO response rate to NIS-Teen was 19.7%, and only 44.0% of households with completed interviews had adequate provider data. A portion of the questionnaires sent to vaccination provider(s) to request the adolescent’s vaccination history were mailed in early 2020. A lower response rate was observed for those requests, likely because of the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on health care provider operations. †††† Second, even with adjustments for household and provider nonresponse, landline-only households, and phoneless households, a bias in the estimates might remain. §§§§ The COVID-19 pandemic has the potential to offset historically high vaccination coverage with Tdap and MenACWY and to reverse gains made in HPV vaccination coverage. Orders for adolescent vaccines have decreased among VFC providers during the pandemic. A recent analysis using VFC provider ordering data showed a decline in vaccine orders for several VFC-funded noninfluenza childhood vaccines since mid-March when COVID-19 was declared a national emergency ( 7 ). CDC, along with other national health organizations, continues to stress the importance of well-child visits and vaccinations as essential services ( 8 ). The majority of practices appear to be open and resuming vaccination activities for their pediatric patients ( 9 , 10 ). Providers can take several steps to ensure that adolescents are up to date with recommended vaccines. These include 1) promoting well-child and vaccination visits; 2) following guidance on safely providing vaccinations during the COVID-19 pandemic ¶¶¶¶ ; 3) leveraging reminder and recall systems to remind parents of their teen’s upcoming appointment, and recalling those who missed appointments and vaccinations; and 4) educating eligible patients and parents, especially those who might have lost employer-funded insurance benefits, about the availability of publicly funded vaccines through the VFC program. In addition, state, local, and territorial immunization programs can consider using available immunization information system data***** to identify local areas and sociodemographic groups at risk for undervaccination related to the pandemic, and to help prioritize resources aimed at improving adolescent vaccination coverage. Summary What is already known about this topic? Three vaccines are routinely recommended for adolescents to prevent diseases that include pertussis, meningococcal disease, and cancers caused by human papillomavirus (HPV). What is added by this report? Adolescent vaccination coverage in the United States continues to improve for HPV and for meningococcal vaccines, with some disparities. Among adolescents living at or above the poverty level, those living outside a metropolitan statistical area (MSA) had lower coverage with HPV and meningococcal vaccines than did those living in MSA principal cities. What are the implications for public health care? Ensuring routine immunization services for adolescents, even during the COVID-19 pandemic, is essential to continuing progress in protecting individuals and communities from vaccine-preventable diseases and outbreaks.

Author and article information

Contributors

Christopher Owens:

(View ORCID Profile)

Randolph D. Hubach:

(View ORCID Profile)

Journal

Title:

The Journal of Rural Health

Abbreviated Title:

The Journal of Rural Health

Publisher:

Wiley

ISSN

(Print):

0890-765X

ISSN

(Electronic):

1748-0361

Publication date

(Electronic):

November

17 2022

Affiliations

Article

DOI: 10.1111/jrh.12726

PubMed ID: 36394371

SO-VID: 9dc2f909-db11-4303-8233-580bdabf31cc

Copyright © ©

2022

History

Data availability: