- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Occupational differences in SARS-CoV-2 infection: analysis of the UK ONS COVID-19 infection survey

Read this article at

Abstract

Background

Concern remains about how occupational SARS-CoV-2 risk has evolved during the COVID-19 pandemic. We aimed to ascertain occupations with the greatest risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and explore how relative differences varied over the pandemic.

Methods

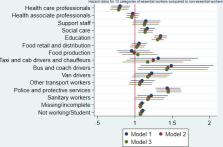

Analysis of cohort data from the UK Office of National Statistics COVID-19 Infection Survey from April 2020 to November 2021. This survey is designed to be representative of the UK population and uses regular PCR testing. Cox and multilevel logistic regression were used to compare SARS-CoV-2 infection between occupational/sector groups, overall and by four time periods with interactions, adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, deprivation, region, household size, urban/rural neighbourhood and current health conditions.

Results

Based on 3 910 311 observations (visits) from 312 304 working age adults, elevated risks of infection can be seen overall for social care (HR 1.14; 95% CI 1.04 to 1.24), education (HR 1.31; 95% CI 1.23 to 1.39), bus and coach drivers (1.43; 95% CI 1.03 to 1.97) and police and protective services (HR 1.45; 95% CI 1.29 to 1.62) when compared with non-essential workers. By time period, relative differences were more pronounced early in the pandemic. For healthcare elevated odds in the early waves switched to a reduction in the later stages. Education saw raises after the initial lockdown and this has persisted. Adjustment for covariates made very little difference to effect estimates.

Related collections

Most cited references35

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Risk of COVID-19 among front-line health-care workers and the general community: a prospective cohort study

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Collider bias undermines our understanding of COVID-19 disease risk and severity

- Record: found

- Abstract: not found

- Book: not found