- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Linking enhancing and impairing effects of emotion—the case of PTSD

editorial

Read this article at

There is no author summary for this article yet. Authors can add summaries to their articles on ScienceOpen to make them more accessible to a non-specialist audience.

Abstract

Introduction

As illustrated by the present Research Topic, emotion that can either enhance or hinder

various aspects of our cognition and behavior. For instance, the emotional charge

of an event can increase attention to and memory for that event (Dolcos et al., 2012),

whereas task-irrelevant emotional information may lead to increased distraction away

from goal-relevant tasks (Iordan et al., 2013; see also Dolcos et al., 2011). Interestingly,

sometimes these opposing effects of emotion co-occur. For example, hearing a gunshot

may enhance memory for central aspects of what was happening at the time, while impairing

memory for peripheral details (Christianson, 1992). It is also possible that increased

distraction from ongoing goals produced by task-irrelevant emotional stimuli may lead

to better memory for the distracting information itself. The co-occurrence of enhancing

and impairing effects of emotion is probably most evident in affective disorders,

where both of these opposing effects are exacerbated. Specifically, uncontrolled recollection

of and rumination on distressing memories observed in depression and post-traumatic

stress disorder (PTSD) may also lead to impaired cognition due to enhanced emotional

distraction. Here, we illustrate an example based on evidence from studies of PTSD,

pointing to the importance of investigating both enhancing and impairing effects of

emotion, in elucidating the nature of alterations in the way emotion interacts with

cognition in clinical conditions.

Background: emotional and cognitive processing in PTSD

Changes in emotional and cognitive processing are critical features in PTSD patients,

typically reflected in increased emotional reactivity and recollection of traumatic

memories, along with impaired cognitive/executive control (Rauch et al., 2006; Shin

and Liberzon, 2009; see also in this issue Brown and Morey, 2012; Hayes et al., 2012).

Of particular note is emerging evidence concerning the neural correlates of alterations

associated with the encoding of emotional memories (Hayes et al., 2011) and with the

responses to task-irrelevant emotional distraction (Morey et al., 2009). These changes

are reflected in regions associated with functions that may be enhanced (episodic

memory) or impaired (working memory) by emotion—i.e., the medial temporal lobe (MTL)

and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC), respectively. Here, we illustrate how

understanding the changes associated with the way traumatic memories are formed and

retrieved in PTSD (involving MTL areas) may clarify their impact on ongoing cognitive/executive

processes (reflected in changes of dlPFC activity), when potential cues for traumatic

memories are presented as task irrelevant distracters.

The enhancing effect of emotion

Studies investigating the memory-enhancing effect of emotion in healthy participants

point to the role of basic MTL mechanisms involving interactions between emotion-based

regions (amygdala—AMY) and memory-related regions (hippocampus and associated parahippocampal

cortices—HC, PHC) in the formation and retrieval of emotional memories (Dolcos et

al., 2012). Neurobiological models of PTSD (Layton and Krikorian, 2002) propose that

the development and maintenance of the disorder is linked to altered activity in the

MTL during encoding of traumatic memories. Hence, intrusive recollection of traumatic

memories observed in PTSD may be linked to dysfunction of the basic MTL mechanism

identified in healthy participants as being responsible for the memory-enhancing effect

of emotion (Dolcos et al., 2004). Specifically, processing of cues related to traumatic

events may trigger recollection of traumatic memories, which due to dysfunctional

interactions between AMY and the MTL memory system may engage a self-sustaining functional

loop in which emotion processing in AMY may enhance recollection by increasing activity

in HC; this, in turn, may intensify AMY activity as a result of re-experiencing the

emotions associated with the recollected memories (Dolcos et al., 2005; McNally, 2006).

On the other hand, there is also evidence suggesting a disconnect between the effects

observed in AMY and their link to emotional or cognitive aspects of processing in

PTSD patients. Specifically, while greater AMY activation is identified in studies

of symptom provocation (Rauch et al., 2000; Hendler et al., 2003; Shin et al., 2004,

2005; Williams et al., 2006), such an effect is not observed in studies of cognitive

processing (Shin et al., 2001; Clark et al., 2003; Bremner et al., 2004; Morey et

al., 2008).

An important observation that has emerged in the PTSD literature may reconcile this

apparent discrepancy. Specifically, there is evidence that memories for negative events

in PTSD patients may be non-specific, gist-based, rather than detailed, context-based

(McNally et al., 1994; Kaspi et al., 1995; Harvey et al., 1998). Gist refers to familiarity-based

retrieval of memories for the general meaning of a situation or event, rather than

recollection of specific contextual details (Tulving, 1985). Given that gist-based

memories are often inaccurate (Roediger and McDermott, 1995; Wright and Loftus, 1998)

and susceptible to enhanced rate of false alarms that may diminish or cancel an actual

enhancing impact of emotion on memory (Dolcos et al., 2005), it may be the case that

the basic AMY-MTL mechanisms typically responsible for the memory-enhancing effect

of emotion are in fact attenuated in PTSD. Hence, this could explain the non-specific,

gist-based, memories observed in these patients. This idea is supported by recent

findings from a fMRI study using the subsequent memory paradigm with emotional stimuli

in PTSD patients (Hayes et al., 2011), which showed reduced memory-related activity

in the AMY-MTL system during memory encoding, and higher false alarm rates during

retrieval, compared to a trauma exposed control (TEC) participants (Figure 1A). Moreover,

the PTSD patients also lacked the anterior posterior dissociation along the longitudinal

axis of the MTL, with respect to its involvement during successful encoding of emotional

memories, which was initially identified in healthy participants (Dolcos et al., 2004),

but such dissociation was preserved in the TEC group (Hayes et al., 2011). Together,

these findings suggest a disorganization of the MTL mechanisms involved in the memory-enhancing

effect of emotion in PTSD, which leads to inefficient encoding of information for

trauma-related stimuli and subsequent non-specific gist-based retrieval.

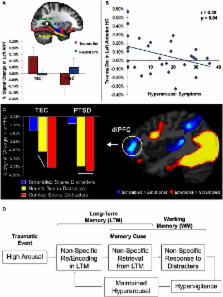

Figure 1

(A–B) Memory-Related Changes in the Medial Temporal Lobe Activity in PTSD. Reduced

memory-related activity (Dm) in AMY for trauma-related pictures, in the PTSD group

(A); a similar effect was also observed in the HC (not shown). Reduced Dm for trauma-related

pictures in the anterior HC linked to increased symptoms of arousal (B). Dm, Difference

due to Memory effect (brain activity for Remembered minus Forgotten items); PTSD,

post-traumatic stress disorder; TEC, Trauma-Exposed Control group; AMY, Amygdala;

HC, Hippocampus; PHC, Parahippocampal Cortex; Ant, Anterior; Post, Posterior. Error

bars represent the standard error of means. Adapted from Hayes et al. (2011), with

permission. (C) Evidence for Non-specific Response in dlPFC to Trauma-Related and

Neutral Distracters in PTSD. Comparison of mean percentage signal change in dlPFC

during the active maintenance period of a working memory task in the PTSD and Trauma-Exposed

Control (TEC) groups point to a generalized dlPFC disruption of activation for salient

task-irrelevant distracter scenes in the PTSD group, which showed an undifferentiated

response in the dlPFC to combat and neutral distracters. The TEC group showed disruption

in the same area, but specific to combat-related distraction. dlPFC, dorsolateral

prefrontal cortex. Adapted from Morey et al. (2009), with permission. (D) Diagram

illustrating a possible link between the impact of emotion on long-term memory and

working memory in PTSD.

The impairing effect of emotion

Studies investigating the neural correlates of the impairing effect of task-irrelevant

emotional distraction on cognitive performance identified distinct patterns of responses

in emotion and cognitive control brain regions (i.e., increased activity in AMY and

reduced activity in dlPFC, respectively), which are specific to emotional distraction

(Dolcos et al., 2011). On the one hand, based on this evidence, increased emotional

reactivity linked to changes in the AMY function in PTSD may lead to increased specific

disruption of dlPFC activity by emotional distraction. On the other hand, there is

evidence for a non-specific heightened sensitivity to both threatening and non-threatening

stimuli in PTSD (Grillon and Morgan, 1999; Peri et al., 2000), which may explain increased

distractibility to trauma related and unrelated stimuli alike.

The fact that information unrelated to the trauma may also be highly distracting in

PTSD patients is consistent with the clinically observed symptom of hypervigilance

in these patients (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), and with the evidence

for non-specific encoding of trauma-related material discussed above (Hayes et al.,

2011). Specifically, it is reasonable to expect that seemingly neutral stimuli that

may remind of trauma could act as cues for non-specific retrieval of trauma-related

information, which in turn may be as distracting as the trauma-related stimuli themselves.

Evidence from a recent study of WM with trauma-related and non-related distraction

is consistent with this idea (Morey et al., 2009). Using an adaptation of our WM task

with emotional distraction (Dolcos and McCarthy, 2006), the study by Morey and colleagues

investigated how trauma-related task-irrelevant emotional information modulates WM

networks in PTSD. Similar to the study on memory encoding discussed above, recent

post-9/11 war veterans were divided into a PTSD group and a TEC group. Functional

MRI results showed that the PTSD group had greater trauma-specific activation than

the control group in main emotion processing brain regions, including the AMY and

ventrolateral PFC (vlPFC), as well as in brain regions susceptible to emotion modulation

(e.g., fusiform gyrus—FG). However, the PTSD group also showed greater non-specific

disruption of activity to combat-related and neutral task-irrelevant distracters in

brain regions that subserve the ability to maintain focus on goal-relevant information,

including the dlPFC. This suggests a more generalized dlPFC disruption in the PTSD

group than in the control group, which showed disruption specific to the trauma-related

distraction. The undifferentiated dlPFC response to combat and non-combat distracters

in PTSD is consistent with the hypervigilance hypothesis that may explain enhanced

response to and distracting effect of neutral stimuli (Figure 1C). This neural-level

finding was complemented by the behavioral results, which showed lower overall working

memory performance for task-irrelevant distracters scenes in the PTSD group, in the

absence of a differential impact between combat-related and neutral distracters.

The link between enhancing and impairing effects of emotion

Overall, the evidence from separate lines of investigations discussed above, regarding

the neural changes in PTSD linked to dysfunctions in the recollection of traumatic

events and the response to emotional distraction, converge toward the idea that non-specific

response to emotional and neutral distraction may reflect retrieval distortions linked

to inefficient initial encoding of trauma-related information. Namely, it is possible

that the non-specific disruption of the dlPFC activity by trauma-related and neutral

distraction is linked to the retrieval of the traumatic memories triggered by non-specific

cues, which may also contribute to the perpetuation of the state of hyperarousal observed

in these patients (Figure 1D). Moreover, it is also possible that the source of these

effects may be linked to elevated arousal during the initial exposure to traumatic

events. Consistent with this idea, in addition to showing non-specific activity to

subsequently remembered items in AMY and MTL memory system in PTSD, the study by Hayes

and colleagues discussed above (Hayes et al., 2011) also identified a negative co-variation

of memory-related hippocampal activity for trauma-related items with scores of hyperarousal

symptoms, as measured with the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (Figure 1B). In other

words, participants who had greater hyperarousal scores also had reduced memory-related

activity during the encoding of trauma-related pictures. This finding is consistent

with evidence for an inverted U-shaped function in the hippocampus as a function of

stress (Nadel and Jacobs, 1998) and provides a possible explanation for the non-specific

effects observed in the tasks assessing emotional memory for trauma-related cues and

their undifferentiated impact on goal-relevant processing when presented as task-irrelevant

distraction. Consistent with the role of the initial arousal in these effects, PTSD

patients also showed relatively greater activity for forgotten items, which may be

linked to AMY hyperactivity leading to later forgetting of those items (Hayes et al.,

2011).

Conclusion

In summary, available evidence from investigations of PTSD patients points to general

and specific emotional and cognitive disturbances that are linked to alterations in

the neural circuitry underlying emotion-cognition interactions. This evidence suggests

that reduction of AMY and HC signals for trauma-related cues may underlie non-specific

encoding of gist-based representations instead of specific and detailed contextual

details of the trauma-related memories. This, in turn, may be linked to symptoms of

hypervigilance and non-specific responses to trauma-related distraction, which contributes

to the maintenance of a hyperarousal state (Figure 1D). This evidence also highlights

the importance of investigating both the enhancing and the impairing effects of emotion,

in understanding the changes associated with affective disorders, where both effects

are intensified. Collectively, these findings point to the importance of investigating

both of these opposing effects of emotion within the same clinical group, to complement

similar approaches in healthy participant concomitantly investigating the enhancing

and impairing effects of emotion on cognitive processes (Shafer and Dolcos, 2012;

Dolcos et al., 2013).

Related collections

Most cited references28

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

The amygdala modulates the consolidation of memories of emotionally arousing experiences.

James McGaugh (2004)

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Neurocircuitry models of posttraumatic stress disorder and extinction: human neuroimaging research--past, present, and future.

Scott L Rauch, Lisa M Shin, Elizabeth A Phelps (2006)

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

A functional magnetic resonance imaging study of amygdala and medial prefrontal cortex responses to overtly presented fearful faces in posttraumatic stress disorder.

Lisa Shin, Christopher I Wright, Paul Cannistraro … (2005)

Author and article information

Comments

Comment on this article

scite_

0

0

0

0

Smart Citations

Smart Citations0

0

0

0

Citing PublicationsSupportingMentioningContrasting

See how this article has been cited at scite.ai

scite shows how a scientific paper has been cited by providing the context of the citation, a classification describing whether it supports, mentions, or contrasts the cited claim, and a label indicating in which section the citation was made.