- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Estimated Life Expectancy and Income of Patients With Sickle Cell Disease Compared With Those Without Sickle Cell Disease

Read this article at

Key Points

Question

What is the association between sickle cell disease and life expectancy and lifetime income?

Findings

This cohort simulation modeling study showed that projected life expectancy (54 vs 76 years) and quality-adjusted life expectancy (33 vs 67 years) were lower in the sickle cell disease cohort relative to the non–sickle cell disease cohort. Projected lifetime income was also lower in individuals with sickle cell disease ($1 227 000 vs $1 922 000), reflecting lost income ($695 000) owing to reduced life expectancy.

Abstract

Importance

Individuals with sickle cell disease (SCD) have reduced life expectancy; however, there are limited data available on lifetime income in patients with SCD.

Objective

To estimate life expectancy, quality-adjusted life expectancy, and income differences between a US cohort of patients with SCD and an age-, sex-, and race/ethnicity-matched cohort without SCD.

Design, Setting, and Participants

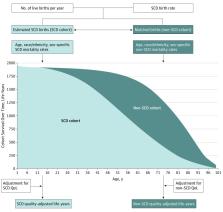

Cohort simulation modeling was used to (1) build a prevalent SCD cohort and a matched non-SCD cohort, (2) identify utility weights for quality-adjusted life expectancy, (3) calculate average expected annual personal income, and (4) model life expectancy, quality-adjusted life expectancy, and lifetime incomes for SCD and matched non-SCD cohorts. Data sources included the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Newborn Screening Information System, and published literature. The target population was individuals with SCD, the time horizon was lifetime, and the perspective was societal. Model data were collected from November 29, 2017, to March 21, 2018, and the analysis was performed from April 28 to December 3, 2018.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Life expectancy, quality-adjusted life expectancy, and projected lifetime income.

Results

The estimated prevalent population for the SCD cohort was 87 328 (95% uncertainty interval, 79 344-101 398); 998 were male and 952 were female. Projected life expectancy for the SCD cohort was 54 years vs 76 years for the matched non-SCD cohort; quality-adjusted life expectancy was 33 years vs 67 years, respectively. Projected lifetime income was $1 227 000 for an individual with SCD and $1 922 000 for a matched individual without SCD, reflecting a lost income of $695 000 owing to the 22-year difference in life expectancy. One study limitation is that the higher estimates of life expectancy yielded conservative estimates of lost life-years and income. The analysis only considered the value of lost personal income owing to premature mortality and did not consider direct medical costs or other societal costs associated with excess morbidity (eg, lost workdays for disability, time spent in the hospital). The model was most sensitive to changes in income levels and mortality rates.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this simulated cohort modeling study, SCD had societal consequences beyond medical costs in terms of reduced life expectancy, quality-adjusted life expectancy, and lifetime earnings. These results underscore the need for disease-modifying therapies to improve the underlying morbidity and mortality associated with SCD.

Abstract

This simulated cohort modeling study compares life expectancy, quality-adjusted life expectancy, and projected lifetime income between individuals with and without sickle cell disease.

Related collections

Most cited references66

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Mortality in sickle cell disease. Life expectancy and risk factors for early death.

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found