- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Risk for In-Hospital Complications Associated with COVID-19 and Influenza — Veterans Health Administration, United States, October 1, 2018–May 31, 2020

research-article

Jordan Cates , PhD

1

,

2

,

,

Cynthia Lucero-Obusan , MD

3 ,

Rebecca M. Dahl , MPH

1 ,

Patricia Schirmer , MD

3 ,

Shikha Garg , MD

1

,

4 ,

Gina Oda , MS

3 ,

Aron J. Hall , DVM

1 ,

Gayle Langley , MD

1 ,

Fiona P. Havers , MD

1 ,

Mark Holodniy , MD

3

,

5 ,

Cristina V. Cardemil , MD

1

,

4

23 October 2020

Read this article at

There is no author summary for this article yet. Authors can add summaries to their articles on ScienceOpen to make them more accessible to a non-specialist audience.

Abstract

On October 20, 2020, this report was posted as an MMWR Early Release on the MMWR website

(https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr).

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is primarily a respiratory illness, although increasing

evidence indicates that infection with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19,

can affect multiple organ systems (

1

). Data that examine all in-hospital complications of COVID-19 and that compare these

complications with those associated with other viral respiratory pathogens, such as

influenza, are lacking. To assess complications of COVID-19 and influenza, electronic

health records (EHRs) from 3,948 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 (March 1–May

31, 2020) and 5,453 hospitalized patients with influenza (October 1, 2018–February

1, 2020) from the national Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the largest integrated

health care system in the United States,* were analyzed. Using International Classification

of Diseases, Tenth Revision,

Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes, complications in patients with laboratory-confirmed

COVID-19 were compared with those in patients with influenza. Risk ratios were calculated

and adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, and underlying medical conditions; proportions

of complications were stratified among patients with COVID-19 by race/ethnicity. Patients

with COVID-19 had almost 19 times the risk for acute respiratory distress syndrome

(ARDS) than did patients with influenza, (adjusted risk ratio [aRR] = 18.60; 95% confidence

interval [CI] = 12.40–28.00), and more than twice the risk for myocarditis (2.56;

1.17–5.59), deep vein thrombosis (2.81; 2.04–3.87), pulmonary embolism (2.10; 1.53–2.89),

intracranial hemorrhage (2.85; 1.35–6.03), acute hepatitis/liver failure (3.13; 1.92–5.10),

bacteremia (2.46; 1.91–3.18), and pressure ulcers (2.65; 2.14–3.27). The risks for

exacerbations of asthma (0.27; 0.16–0.44) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

(COPD) (0.37; 0.32–0.42) were lower among patients with COVID-19 than among those

with influenza. The percentage of COVID-19 patients who died while hospitalized (21.0%)

was more than five times that of influenza patients (3.8%), and the duration of hospitalization

was almost three times longer for COVID-19 patients. Among patients with COVID-19,

the risk for respiratory, neurologic, and renal complications, and sepsis was higher

among non-Hispanic Black or African American (Black) patients, patients of other races,

and Hispanic or Latino (Hispanic) patients compared with those in non-Hispanic White

(White) patients, even after adjusting for age and underlying medical conditions.

These findings highlight the higher risk for most complications associated with COVID-19

compared with influenza and might aid clinicians and researchers in recognizing, monitoring,

and managing the spectrum of COVID-19 manifestations. The higher risk for certain

complications among racial and ethnic minority patients provides further evidence

that certain racial and ethnic minority groups are disproportionally affected by COVID-19

and that this disparity is not solely accounted for by age and underlying medical

conditions.

The study population comprised two cohorts of hospitalized adult (aged ≥18 years)

VHA patients: 1) those with nasopharyngeal (90%) or other specimens that had tested

positive for SARS-CoV-2 by real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction

(RT-PCR) during March 1–May 31, 2020, and 2) those with laboratory-confirmed influenza

A or B by rapid antigen assay, real-time RT-PCR, direct or indirect fluorescent staining,

or viral culture, during October 1, 2018–February 1, 2020. Patients who received an

influenza diagnosis after February 1, 2020, were excluded to minimize the possible

inclusion of patients co-infected with SARS-CoV-2. Patients were restricted to those

with a COVID-19 or influenza test during hospitalization or in the 30 days preceding

hospitalization (including inpatient care at a nursing home). Patients who were still

hospitalized as of July 31, 2020, or who were admitted >14 days before receiving testing

were excluded from the analysis.

Data from EHRs were extracted from VHA Praedico Surveillance System, a biosurveillance

application used for early detection, monitoring, and forecasting of infectious disease

outbreaks

†

and Corporate Data Warehouse. Data included age, sex, race/ethnicity, ICD-10-CM diagnosis

codes, hospital admission and discharge date, and, if applicable, date of intensive

care unit (ICU) admission and date of death. Thirty-three acute complications (not

mutually exclusive) were identified using ICD-10-CM codes from the hospitalization

EHR (

2

). Underlying medical conditions were identified using ICD-10-CM codes from inpatient,

outpatient, and problem list records from at least 14 days before the specimen collection

date (

3

).

Categorical variables were compared using Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test and continuous

variables with Wilcoxon rank sum test. Two-sided p-values <0.05 were considered statistically

significant. Among patients with COVID-19, the risk for complications was compared

among racial/ethnic groups using log-binomial models, adjusting for age and underlying

medical conditions, with White patients as the reference group. Relative risk for

complications in patients with COVID-19 compared with those with influenza were estimated

using log-binomial models, adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, and underlying

medical conditions. To assess bias from seasonality in complications unrelated to

influenza or COVID-19, a sensitivity analysis restricted to cases diagnosed during

March–May of 2019 (influenza) and March–May of 2020 (COVID-19) was conducted. All

analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute). The data used in this

analysis were obtained for the purpose of public health operations in VHA.

§

Because no additional analyses were performed outside public health operational activities,

the activity was determined to meet the requirements of public health surveillance

as defined in 45 CFR 46.102(l)(2), and Institutional Review Board review was not required.

During October 1, 2018–February 1, 2020, 5,746 hospitalized patients received a positive

influenza test result and during March 1–May 31, 2020, 4,305 hospitalized patients

received a positive SARS-CoV-2 test result. For both groups, testing occurred during

the 30 days preceding hospitalization or while hospitalized. A total of 132 patients

admitted >14 days before testing were excluded, as were 518 patients who were still

hospitalized as of July 31, 2020, leaving 5,453 influenza patients and 3,948 COVID-19

patients for analysis.

Patients with COVID-19 were slightly older than were those with influenza (median = 70

years; interquartile range [IQR] = 61–77 years versus 69 years; IQR = 61–75 years)

(p = 0.001), but patients with influenza had higher prevalences of most underlying

medical conditions than did those with COVID-19 (Table 1). Black patients accounted

for 48.3% of COVID-19 patients and 24.7% of influenza patients; the proportion of

Hispanic patients was similar in both groups. The percentage of COVID-19 patients

admitted to an ICU (36.5%) was more than twice that of influenza patients (17.6%);

the percentage of COVID-19 patients who died while hospitalized (21.0%) was more than

five times that of influenza patients (3.8%); and the duration of hospitalization

was almost three times longer for COVID-19 patients (median 8.6 days; IQR = 3.9–18.6

days) than that for influenza patients (3.0 days; 1.8–6.5 days) (p<0.001 for all).

TABLE 1

Demographics, underlying medical conditions, acute complications, and hospital outcomes

among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 (March 1–May 31, 2020) and among historically

hospitalized patients with influenza (October 1, 2018–February 1, 2020)* — Veterans

Health Administration, United States

Characteristic or condition

No. (%)

P-value

COVID-19

Influenza

Baseline characteristics

No. of patients

3,948

5,453

—

Median age at test date, yrs (IQR)

70 (61–77)

69 (61–75)

0.001

Male

3,710 (94.0)

5,116 (93.8)

0.76

Race/Ethnicity

White, non-Hispanic

1,515 (40.4)

3,389 (64.0)

<0.001

Black, non-Hispanic

1,811 (48.3)

1,305 (24.7)

Other race, non-Hispanic†

87 (2.3)

150 (2.8)

Hispanic or Latino

336 (9.0)

449 (8.5)

Underlying medical conditions§

Asthma

260 (6.9)

565 (10.5)

<0.001

COPD

903 (23.9)

2,261 (42.0)

<0.001

Other lung conditions

534 (14.1)

1,078 (20.0)

<0.001

Blood disorders

123 (3.2)

257 (4.8)

<0.001

Cerebrovascular diseases

468 (12.4)

558 (10.4)

<0.001

Heart disease

1,909 (50.4)

3,068 (57.0)

<0.001

Heart failure

707 (18.7)

1,320 (24.5)

<0.001

Hypertension

2,893 (76.4)

4,082 (75.9)

0.77

Diabetes mellitus

1,873 (49.5)

2,416 (44.9)

<0.001

Renal conditions

1,111 (29.4)

1,468 (27.3)

0.03

Liver diseases

528 (13.9)

687 (12.8)

0.10

Immunosuppression

537 (14.2)

1,033 (19.2)

<0.001

Long-term medication use

451 (11.9)

776 (14.4)

<0.001

Cancer

696 (18.4)

1,341 (24.9)

<0.001

Neurologic/Musculoskeletal

1,602 (42.3)

2,091 (38.9)

<0.001

Endocrine disorders

620 (16.4)

996 (18.5)

0.01

Metabolic conditions

2,525 (66.7)

3,628 (67.5)

0.45

Extreme obesity

333 (8.8)

518 (9.6)

0.18

Any underlying medical condition¶

3,541 (93.6)

5,117 (95.1)

0.001

In-hospital complications**

Respiratory

3,030 (76.8)

5,167 (94.8)

<0.001

Pneumonia

2,766 (70.1)

1,916 (35.1)

<0.001

Respiratory failure

1,834 (46.5)

1,556 (28.5)

<0.001

ARDS

369 (9.3)

29 (0.5)

<0.001

Asthma exacerbation, no./No. (%)††

17/260 (6.5)

127/565 (22.5)

<0.001

COPD exacerbation, no./No. (%)††

160/903 (17.7)

1,154/2,261 (51.0)

<0.001

Pneumothorax

24 (0.6)

9 (0.2)

<0.001

Cardiovascular

516 (13.1)

911 (16.7)

<0.001

Acute MI/Unstable angina

300 (7.6)

499 (9.2)

0.01

Acute CHF

216 (5.5)

467 (8.6)

<0.001

Cardiogenic shock

36 (0.9)

28 (0.5)

0.02

Hypertensive crisis

53 (1.3)

90 (1.7)

0.23

Acute myocarditis

23 (0.6)

11 (0.2)

0.002

Hematologic

244 (6.2)

135 (2.5)

<0.001

Deep vein thrombosis

131 (3.3)

62 (1.1)

<0.001

Pulmonary embolism

112 (2.8)

72 (1.3)

<0.001

DIC

18 (0.5)

6 (0.1)

0.001

Neurologic

161 (4.1)

116 (2.1)

<0.001

Cerebral ischemia/infarction

125 (3.2)

92 (1.7)

<0.001

Intracranial hemorrhage

27 (0.7)

10 (0.2)

<0.001

Endocrine

79 (2.0)

80 (1.5)

0.05

Diabetic ketoacidosis, no./No. (%)††

42/1,873 (2.2)

42/2,416 (1.7)

0.24

Gastrointestinal

77 (2.0)

200 (3.7)

<0.001

Acute hepatitis/liver failure

63 (1.6)

26 (0.5)

<0.001

Renal

1,562 (39.6)

1,434 (26.3)

<0.001

Acute kidney failure

1,541 (39.0)

1,413 (25.9)

<0.001

Dialysis initiation§§

120 (3.0)

39 (0.7)

<0.001

Other¶¶

1,249 (31.6)

1,258 (23.1)

<0.001

Sepsis

984 (24.9)

1,012 (18.6)

<0.001

Bacteremia

186 (4.7)

100 (1.8)

<0.001

Pressure ulcer

289 (7.3)

144 (2.6)

<0.001

Hospital outcomes

Length of stay, days (IQR)

8.6 (3.9–18.6)

3.0 (1.8–6.5)

<0.001

ICU admission

1,421 (36.5)

961 (17.6)

<0.001

In-hospital mortality

828 (21.0)

190 (3.8)

<0.001

Abbreviations: ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome; CHF = congestive heart

failure; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease

2019; DIC = disseminated intravascular coagulation; ICU = intensive care unit; IQR = interquartile

range; MI = myocardial infarction.

* Data on race or ethnicity were missing for 199 (5.0%) patients with COVID-19 and

160 (2.9%) patients with influenza; data on underlying medical conditions were missing

for 163 (4.1%) patients with COVID-19 and 75 (1.4%) patients with influenza; and data

on ICU admission was missing for 49 (1.2%) patients with COVID-19. P-values were calculated

from Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank

sum test for continuous variables.

† Among patients with COVID-19, non-Hispanic Other included 22 patients with multiple

races documented, 22 American Indians or Alaska Natives, 29 Asians, and 14 Native

Hawaiians or other Pacific Islanders. Among patients with influenza, non-Hispanic

Other included 47 patients with multiple races documented, 34 American Indians or

Alaska Natives, 29 Asians, and 40 Native Hawaiians or other Pacific Islanders.

§ Coding of underlying medical conditions was based on International Classification

of Diseases, Tenth Revision,

Clinical Modification, (ICD-10-CM) codes and grouping into categories was based primarily

on established categorizations from the CDC Hospitalized Adult Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness

Network.

¶ Excluding hypertension only.

** Complications are not mutually exclusive. Acute complications primarily identified

using a list of ICD-10-CM codes published by Chow EJ, Rolfes MA, O'Halloran A, et

al. (https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2762991). Complications

assessed but not included in Chow et al. include pressure ulcers (ICD-10-CM code L89*)

and dialysis initiation (ICD-10-CM codes Z49, Z99.2, Z95.3, and Z91.15 and Current

Procedural Terminology codes 90935, 90937, 90940, 90945, 90947, 90999, 0505F, 4045F,

36800, 36810, and 36816).

†† Denominator restricted to patients with the underlying medical condition related

to the complication (asthma, COPD, or diabetes mellitus).

§§ Indication of dialysis during hospitalization without indication of dialysis within

the past year.

¶¶ Other rare complications reported in <1% of patients with COVID-19 included acute

pericarditis (seven, 0.2%), immune thrombocytopenic purpura (seven, 0.2%), Guillain-Barre

Syndrome (six, 0.2%), encephalitis (seven, 0.2%), acute disseminated encephalomyelitis

and encephalomyelitis (one, <0.1%), thyrotoxicosis (19, 0.5%), hyperglycemic hyperosmolar

syndrome (14, 0.4%), acute pancreatitis (16, 0.4%), rhabdomyolysis (83, 2.1%), and

autoimmune hemolytic anemia (one, <0.1%).

Among patients with COVID-19, 76.8% had respiratory complications, including pneumonia

(70.1%), respiratory failure (46.5%), and ARDS (9.3%). Nonrespiratory complications

were frequent, including renal (39.6%), cardiovascular (13.1%), hematologic (6.2%),

and neurologic complications (4.1%), as well as sepsis (24.9%) and bacteremia (4.7%);

24.1% of COVID-19 patients had complications involving three or more organ systems.

Among COVID-19 patients, nine complications were more prevalent among racial and ethnic

minority patients, including respiratory, neurologic, and renal complications, even

after adjustment for age and underlying medical conditions (Table 2).

TABLE 2

Proportions and adjusted relative risk of selected COVID-19 respiratory and nonrespiratory

complications,* by race/ethnicity

†

— Veterans Health Administration, United States, March 1–May 31, 2020

Complication

White, non-Hispanic

(N = 1,515)

Black or African American, non-Hispanic

(N = 1,811)

Other race, non-Hispanic§

(N = 87)

Hispanic or Latino

(N = 336)

P-value**

No. (%)

No. (%)

aRR (95% CI)¶

No. (%)

aRR (95% CI)¶

No. (%)

aRR (95% CI)¶

Pneumonia

967 (63.8)

1,322 (73.0)

1.15 (1.10–1.21)

64 (73.6)

1.15 (1.01–1.31)

257 (76.5)

1.21 (1.13–1.31)

<0.001

Respiratory failure

656 (43.3)

860 (47.5)

1.14 (1.06–1.23)

48 (55.2)

1.30 (1.08–1.58)

158 (47.0)

1.13 (0.99–1.28)

0.03

ARDS

118 (7.8)

177 (9.8)

1.25 (1.00–1.57)

15 (17.2)

2.06 (1.24–3.43)

38 (11.3)

1.32 (0.92–1.91)

0.01

Hypertensive crisis

11 (0.7)

33 (1.8)

2.27 (1.13–4.54)

3 (3.4)

4.03 (1.14–14.21)

2 (0.6)

0.87 (0.19–3.90)

0.01

Cerebral ischemia/infarction

29 (1.9)

69 (3.8)

2.42 (1.57–3.74)

2 (2.3)

1.34 (0.33–5.50)

17 (5.1)

3.44 (1.92–6.18)

<0.01

Intracranial hemorrhage

6 (0.4)

15 (0.8)

2.45 (0.88–6.80)

3 (3.4)

10.36 (2.54–42.31)

3 (0.9)

2.69 (0.64–11.25)

0.02

Acute kidney failure

483 (31.9)

845 (46.7)

1.40 (1.28–1.53)

36 (41.4)

1.29 (1.01–1.66)

108 (32.1)

1.06 (0.89–1.26)

<0.001

Dialysis initiation

21 (1.4)

83 (4.7)

2.92 (1.81–4.71)

2 (2.4)

1.47 (0.35–6.16)

9 (2.9)

2.09 (0.97–4.52)

<0.001

Sepsis

306 (20.2)

496 (27.4)

1.42 (1.25–1.61)

29 (33.3)

1.71 (1.25–2.34)

91 (27.1)

1.40 (1.14–1.73)

<0.001

Abbreviations: ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome; aRR = adjusted risk ratio;

CI = confidence interval; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019.

* Complications are not mutually exclusive. Other complications assessed but not statistically

different (p-value >0.05) across strata of race/ethnicity included pneumothorax, asthma

and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation, acute myocardial infarction/unstable

angina, acute congestive heart failure, acute myocarditis, cardiogenic shock, deep

vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, disseminated intravascular coagulation, diabetic

ketoacidosis, acute hepatitis/liver failure, bacteremia, and pressure ulcers.

† Data on race/ethnicity were missing for 199 (5.0%) of COVID-19 patients and were

excluded from the race/ethnicity stratification.

§ Other, non-Hispanic category included 22 patients with multiple races documented,

22 American Indians or Alaska Natives, 29 Asians, and 14 Native Hawaiians or other

Pacific Islanders.

¶ Separate log-binomial models were run to estimate aRRs for each complication. Pneumonia,

respiratory failure, and ARDS models adjusted for age, COPD, asthma, and other lung

diseases; hypertensive crisis model adjusted for age, hypertension, heart disease,

and heart failure; cerebral ischemia/infarction and intracranial hemorrhage models

controlled for age, underlying cerebrovascular diseases, neurologic/musculoskeletal

conditions, heart disease, and heart failure; acute kidney failure and dialysis models

controlled for age, underlying renal disease, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension.

** P-values calculated from Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test to compare frequencies

of complications among strata of race/ethnicity.

Compared with patients with influenza, patients with COVID-19 had two times the risk

for pneumonia; 1.7 times the risk for respiratory failure; 19 times the risk for ARDS;

3.5 times the risk for pneumothorax; and statistically significantly increased risks

for cardiogenic shock, myocarditis, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, disseminated

intravascular coagulation, cerebral ischemia or infarction, intracranial hemorrhage,

acute kidney failure, dialysis initiation, acute hepatitis or liver failure, sepsis,

bacteremia, and pressure ulcers (Figure). Patients with COVID-19 had a lower risk

for five complications (asthma exacerbation, COPD exacerbation, acute myocardial infarction

(MI) or unstable angina, acute congestive heart failure (CHF), and hypertensive crisis),

although acute MI or unstable angina, acute CHF, and hypertensive crisis were not

statistically significant when restricting to patients diagnosed during the same seasonal

months.

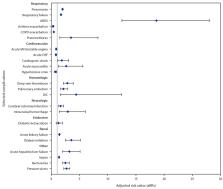

FIGURE

Adjusted relative risk* for selected acute respiratory and nonrespiratory complications

in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 (March 1– May 31, 2020), compared with historically

hospitalized patients with influenza (October 1, 2018–February 1, 2020) — Veterans

Health Administration, United States

†

,

§

,

¶

Abbreviations: ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome; CHF = congestive heart

failure; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DIC = disseminated intravascular

coagulation; MI = myocardial infarction.

* 95% confidence intervals (CIs) indicated with error bars.

† When restricted to patients with influenza during the same seasonal months (March–May),

aRRs and 95% CIs for acute MI or unstable angina, acute CHF, and hypertensive crisis

were 0.90 (0.74–1.11), 1.03 (0.82–1.28), and 0.75 (0.44–1.29), respectively.

§ Dialysis during hospitalization was identified using International Classification

of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification and current procedural terminology

codes, and new initiation of dialysis was determined by excluding patients with indication

of dialysis within the past year.

¶ Separate crude and adjusted log-binomial models were run for each complication (which

were not mutually exclusive). All adjusted models adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity,

and outcome-specific underlying conditions. Specifically, respiratory complication

models controlled for COPD, asthma, and other lung diseases; neurologic complication

models controlled for underlying cerebrovascular diseases, neurological/musculoskeletal

conditions, heart disease, and heart failure; cardiovascular and hematologic condition

models controlled for heart disease, heart failure, renal conditions, diabetes mellitus,

and extreme obesity; the acute kidney failure model controlled for underlying renal

disease, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension. Complications related to the worsening

of a chronic medical condition were restricted to those patients with that underlying

medical condition.

The figure is a forest plot showing the adjusted relative risk for selected acute

respiratory and nonrespiratory complications in hospitalized patients with COVID-19

(March 1–May 31, 2020), compared with historically hospitalized patients with influenza

(October 1, 2018–February 1, 2020) among U.S. patients in the Veterans Health Administration

system.

Discussion

Findings from a large, national cohort of patients hospitalized within the VHA illustrate

the increased risk for complications involving multiple organ systems among patients

with COVID-19 compared with those with influenza, as well as racial/ethnic disparities

in COVID-19–associated complications. Compared with patients with influenza, those

with COVID-19 had a more than five times higher risk for in-hospital death and approximately

double the ICU admission risk and hospital length of stay, and were at higher risk

for 17 acute respiratory, cardiovascular, hematologic, neurologic, renal and other

complications. Racial and ethnic disparities in the percentage of complications among

patients with COVID-19 was found for respiratory, neurologic, and renal complications,

as well as for sepsis.

Persons from racial and ethnic minority groups are increasingly recognized as having

higher rates of COVID-19, associated hospitalizations, and increased risk for severe

in-hospital outcomes (

4

,

5

). Although previous analysis of VHA data found no differences in COVID-19 mortality

by race/ethnicity (

4

), in this analysis, Black, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic patients of other races had

higher risks for sepsis and respiratory, neurologic, and renal complications than

did White patients. The disparities in acute complications among racial and ethnic

minority groups could not solely be accounted for by differences in underlying medical

conditions or age and might be affected by social, environmental, economic, and structural

inequities.

¶

Elucidation of the reasons for these disparities is urgently needed to advance health

equity for all persons.

The risk for respiratory complications was high, consistent with current knowledge

of SARS-CoV-2 and influenza pathogenesis (

1

,

6

). Notably, compared with patients with influenza, patients with COVID-19 had two

times the risk for pneumonia, 1.7 times the risk for respiratory failure, 19 times

the risk for ARDS, and 3.5 times the risk for pneumothorax, underscoring the severity

of COVID-19 respiratory illness relative to that of influenza. Conversely, the risk

for asthma and COPD exacerbations was approximately three times lower among patients

with COVID-19 than among those with influenza.

The risk for certain acute nonrespiratory complications was also high, including the

risk for sepsis and renal and cardiovascular complications. Patients with COVID-19

were at increased risk for acute kidney failure requiring dialysis than were patients

with influenza, consistent with previous evidence of influenza- (

2

) and COVID-19–associated (

7

) acute kidney failure. The frequent occurrence and increased risk for sepsis among

patients with COVID-19 is consistent with reports of dysregulated immune response

in these patients (

8

). The distribution of cardiovascular complications differed between patients with

influenza and those with COVID-19; patients with COVID-19 experienced lower risk for

acute MI, unstable angina, and acute CHF but higher risk for acute myocarditis and

cardiogenic shock. There were no significant differences in occurrence of acute MI,

unstable angina, and CHF among patients with COVID-19 or influenza diagnosed during

the same months, suggesting potential confounding by seasonal variations in cardiovascular

disease.

Other less common (<10%), but often severe complications included hematologic and

neurologic complications, bacteremia, and pressure ulcers. Whereas other viruses,

like influenza, might cause proinflammatory cytokines and clot formation (

6

), the findings from this study suggest that hematologic complications are a much

more frequent complication of COVID-19, consistent with previous reports of COVID-19–related

thromboembolic events (

1

,

9

). A New York City study reported that the odds of stroke were 7.6 times higher among

COVID-19 patients than among those with influenza (

10

), which is consistent with the present findings of a twofold increase in the risk

for cerebral ischemia or infarction. Patients with COVID-19 might be at increased

risk for pressure ulcers related to prolonged hospitalizations, prone positioning,

or both.

The findings in this report are subject to at least six limitations. First, administrative

codes might have limited sensitivity and specificity for capturing conditions and

might misclassify chronic conditions as acute. Extreme obesity was defined based solely

on ICD-10-CM codes and not body mass index, resulting in potential misclassification

and residual confounding. Second, clinician-ordered testing could potentially underestimate

some complications in patients with less typical respiratory symptoms. Third, the

analysis of racial differences was limited by the small sample size within the non-Hispanic

Other race group. Fourth, the generalizability of results might be limited by the

diversity and moderate severity among adults of the predominant circulating influenza

type/subtype during the period of this analysis (A H3N2 in 2018–2019 and A H1N1 and

B in 2019–2020).** Fifth, influenza vaccination or treatments for COVID-19 or influenza

that might affect these outcomes were not examined. Finally, this analysis did not

adjust for region or facility size or type, and further research is warranted to assess

the impact of these factors on the risk for COVID-19 complications.

Hospitalized adult VHA patients with COVID-19 experienced a higher risk for respiratory

and nonrespiratory complications and death than did hospitalized patients with influenza.

Disparities by race/ethnicity in experiencing sepsis and respiratory, neurologic,

and renal complications, even after adjustment for age and underlying medical conditions,

provide further evidence that racial and ethnic minority groups are disproportionally

affected by COVID-19. Clinicians should be vigilant for symptoms and signs of a spectrum

of complications among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 so that interventions can

be instituted to improve outcomes and reduce long-term disability.

Summary

What is already known about this topic?

Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 are reported to be at risk for respiratory and

nonrespiratory complications.

What is added by this report?

Hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in the Veterans Health Administration had a more

than five times higher risk for in-hospital death and increased risk for 17 respiratory

and nonrespiratory complications than did hospitalized patients with influenza. The

risks for sepsis and respiratory, neurologic, and renal complications of COVID-19

were higher among non-Hispanic Black or African American and Hispanic patients than

among non-Hispanic White patients.

What are the implications for public health practice?

Compared with influenza, COVID-19 is associated with increased risk for most respiratory

and nonrespiratory complications. Certain racial and ethnic minority groups are disproportionally

affected by COVID-19.

Related collections

Most cited references10

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19

Aakriti Gupta, Mahesh Madhavan, Kartik Sehgal … (2020)

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

COVID-19 and its implications for thrombosis and anticoagulation

Jean M Connors, Jerrold Levy (2020)

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

SARS-CoV-2 and viral sepsis: observations and hypotheses

Hui LI, Liang Liu, Dingyu Zhang … (2020)