- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Association of Alzheimer Disease With Life Expectancy in People With Down Syndrome

Read this article at

Abstract

This meta-analysis assesses whether the variability in symptom onset of Alzheimer disease in Down syndrome is similar to autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease and its association with mortality.

Key Points

Question

Is age at onset of Alzheimer disease in people with Down syndrome as consistent as in autosomal dominant forms, and is the association of the disease with mortality compatible with near full penetrance?

Abstract

Importance

People with Down syndrome have a high risk of developing Alzheimer disease dementia. However, penetrance and age at onset are considered variable, and the association of this disease with life expectancy remains unclear because of underreporting in death certificates.

Objective

To assess whether the variability in symptom onset of Alzheimer disease in Down syndrome is similar to autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease and to assess its association with mortality.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This study combines a meta-analysis with the assessment of mortality data from US death certificates (n = 77 347 case records with a International Classification of Diseases code for Down syndrome between 1968 to 2019; 37 900 [49%] female) and from a longitudinal cohort study (n = 889 individuals; 46% female; 3.2 [2.1] years of follow-up) from the Down Alzheimer Barcelona Neuroimaging Initiative (DABNI).

Main Outcomes and Measures

A meta-analysis was conducted to investigate the age at onset, age at death, and duration of Alzheimer disease dementia in Down syndrome. PubMed/Medline, Embase, Web of Science, and CINAHL were searched for research reports, and OpenGray was used for gray literature. Studies with data about the age at onset or diagnosis, age at death, and disease duration were included. Pooled estimates with corresponding 95% CIs were calculated using random-effects meta-analysis. The variability in disease onset was compared with that of autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease. Based on these estimates, a hypothetical distribution of age at death was constructed, assuming fully penetrant Alzheimer disease. These results were compared with real-world mortality data.

Results

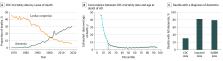

In this meta-analysis, the estimate of age at onset was 53.8 years (95% CI, 53.1-54.5 years; n = 2695); the estimate of age at death, 58.4 years (95% CI, 57.2-59.7 years; n = 324); and the estimate of disease duration, 4.6 years (95% CI, 3.7-5.5 years; n = 226). Coefficients of variation and 95% prediction intervals of age at onset were comparable with those reported in autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease. US mortality data revealed an increase in life expectancy in Down syndrome (median [IQR], 1 [0.3-16] years in 1968 to 57 [49-61] years in 2019), but with clear ceiling effects in the highest percentiles of age at death in the last decades (90th percentile: 1990, age 63 years; 2019, age 65 years). The mortality data matched the limits projected by a distribution assuming fully penetrant Alzheimer disease in up to 80% of deaths (corresponding to the highest percentiles). This contrasts with dementia mentioned in 30% of death certificates but is in agreement with the mortality data in DABNI (78.9%). Important racial disparities persisted in 2019, being more pronounced in the lower percentiles (10th percentile: Black individuals, 1 year; White individuals, 30 years) than in the higher percentiles (90th percentile: Black individuals, 64 years; White individuals, 66 years).

Related collections

Most cited references97

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis.

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Clinical and Biomarker Changes in Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer's Disease

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found