- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Racial Disparities in COVID-19 Testing and Outcomes : Retrospective Cohort Study in an Integrated Health System

Read this article at

Abstract

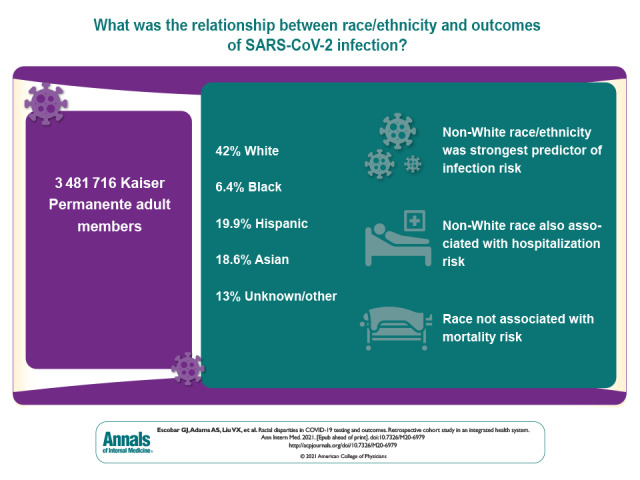

In a retrospective cohort study based on data from adult members of a large integrated health system, the authors assessed the contribution of age, sex, race/ethnicity, neighborhood of residence, comorbidities, and measures of acute physiology to rates of COVID-19 testing, infection, hospitalization, mortality, and other health outcomes.

Abstract

In a retrospective cohort study based on data from adult members of a large integrated health system, the authors assessed the contribution of age, sex, race/ethnicity, neighborhood of residence, comorbidities, and measures of acute physiology to rates of COVID-19 testing, infection, hospitalization, mortality, and other health outcomes.

Abstract

Background:

Racial disparities exist in outcomes after severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection.

Objective:

To evaluate the contribution of race/ethnicity in SARS-CoV-2 testing, infection, and outcomes.

Measurements:

Age, sex, neighborhood deprivation index, comorbid conditions, acute physiology indices, and race/ethnicity; SARS-CoV-2 testing and incidence of positive test results; and hospitalization, illness severity, and mortality.

Results:

Among 3 481 716 eligible members, 42.0% were White, 6.4% African American, 19.9% Hispanic, and 18.6% Asian; 13.0% were of other or unknown race. Of eligible members, 91 212 (2.6%) were tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection and 3686 had positive results (overall incidence, 105.9 per 100 000 persons; by racial group, White, 55.1; African American, 123.1; Hispanic, 219.6; Asian, 111.7; other/unknown, 79.3). African American persons had the highest unadjusted testing and mortality rates, White persons had the lowest testing rates, and those with other or unknown race had the lowest mortality rates. Compared with White persons, adjusted testing rates among non-White persons were marginally higher, but infection rates were significantly higher; adjusted odds ratios [aORs] for African American persons, Hispanic persons, Asian persons, and persons of other/unknown race were 2.01 (95% CI, 1.75 to 2.31), 3.93 (CI, 3.59 to 4.30), 2.19 (CI, 1.98 to 2.42), and 1.57 (CI, 1.38 to 1.78), respectively. Geographic analyses showed that infections clustered in areas with higher proportions of non-White persons. Compared with White persons, adjusted hospitalization rates for African American persons, Hispanic persons, Asian persons, and persons of other/unknown race were 1.47 (CI, 1.03 to 2.09), 1.42 (CI, 1.11 to 1.82), 1.47 (CI, 1.13 to 1.92), and 1.03 (CI, 0.72 to 1.46), respectively. Adjusted analyses showed no racial differences in inpatient mortality or total mortality during the study period. For testing, comorbid conditions made the greatest relative contribution to model explanatory power (77.9%); race only accounted for 8.1%. Likelihood of infection was largely due to race (80.3%). For other outcomes, age was most important; race only contributed 4.5% for hospitalization, 12.8% for admission illness severity, 2.3% for in-hospital death, and 0.4% for any death.

Related collections

Most cited references29

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

OpenSAFELY: factors associated with COVID-19 death in 17 million patients

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Factors associated with hospital admission and critical illness among 5279 people with coronavirus disease 2019 in New York City: prospective cohort study

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found