- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

BMI Cut Points to Identify At-Risk Asian Americans for Type 2 Diabetes Screening

review-article

William C. Hsu

1

,

,

Maria Rosario G. Araneta

2 ,

Alka M. Kanaya

3 ,

Jane L. Chiang

4 ,

Wilfred Fujimoto

5

13 December 2014

Read this article at

There is no author summary for this article yet. Authors can add summaries to their articles on ScienceOpen to make them more accessible to a non-specialist audience.

Abstract

Asian American Population

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, an Asian is a person with origins from the Far

East (China, Japan, Korea, and Mongolia), Southeast Asia (Cambodia, Malaysia, the

Philippine Islands, Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia, Singapore, Laos, etc.), or the Indian

subcontinent (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Sri Lanka, and Nepal); each region

has several ethnicities, each with a unique culture, language, and history. In 2011,

18.2 million U.S. residents self-identified as Asian American, with more than two-thirds

foreign-born (1). In 2012, Asian Americans were the nation’s fastest-growing racial

or ethnic group, with a growth rate over four times that of the total U.S. population.

International migration has contributed >60% of the growth rate in this population

(1). Among Asian Americans, the Chinese population was the largest (4.0 million),

followed by Filipinos (3.4 million), Asian Indians (3.2 million), Vietnamese (1.9

million), Koreans (1.7 million), and Japanese (1.3 million). Nearly three-fourths

of all Asian Americans live in 10 states—California, New York, Texas, New Jersey,

Hawaii, Illinois, Washington, Florida, Virginia, and Pennsylvania (1). By 2060, the

Asian American population is projected to more than double to 34.4 million, with its

share of the U.S. population climbing from 5.1 to 8.2% in the same period (2).

Overweight/Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes Risk for Asian Americans

Although it is clear that increased body weight is a risk factor for type 2 diabetes,

the relationship between body weight and type 2 diabetes is more properly attributable

to the quantity and distribution of body fat (3–5). Abdominal circumference and waist

and hip measurements, although highly correlated with cardiometabolic risk (6,7),

do not differentiate subcutaneous from visceral adipose abdominal depots and are subject

to interobserver variability. Imaging and other approaches can be used to more accurately

assess fat distribution and quantify adiposity (4,8), but they are not readily available,

economical, or useable on a large scale. Therefore, the measurement of body weight

with various corrections for height is frequently used to assess risk for obesity-related

diseases because it is the most economical and practical approach in both clinical

and epidemiologic settings (9). The most commonly used measure is Quetelet’s index

or BMI, defined as weight ÷ height2, with weight in kilograms and height in meters.

However, BMI does not take into account the relative proportions of fat and lean tissue

and cannot distinguish the location of fat distribution (10,11).

The clinical value of measuring BMI from a diabetes diagnosis perspective lies in

whether this measure can identify individuals who may have undiagnosed diabetes or

may be at increased future risk for diabetes. In addition, measuring BMI also is important

for managing diabetes for the purpose of weight control. BMI cutoffs have been established

to identify overweight (BMI ≥25 kg/m2) or obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) individuals (12).

However, these are based on information derived from the general population, based

on risk of mortality, without consideration for racial or ethnic specificity and were

not determined to specifically identify those at risk for diabetes. Recently, the

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention presented initial findings from an

oversampling of Asian Americans in the 2011–2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination

Survey. These data, utilizing general population criteria for obesity, showed the

prevalence of obesity in Asian Americans was only 10.8% compared with 34.9% in all

U.S. adults (13). Paradoxically, many studies from Asia, as well as research conducted

in several Asian American populations, have shown that diabetes risk has increased

remarkably in populations of Asian origin, although in general these populations have

a mean BMI significantly lower than defined at-risk BMI levels (14,15). Moreover,

U.S. clinicians who care for Asian patients have noticed that many with diabetes do

not meet the published criteria for obesity or even overweight (16).

Epidemiologic studies have shown that there is a relationship between BMI and diabetes

risk in Asians, but this risk is shifted to lower BMI values (17). At similar BMI

levels, diabetes prevalence has been identified as higher in Asians compared with

whites (18). This paradox may be partly explained by a difference in body fat distribution:

there is a propensity for Asians to develop visceral versus peripheral adiposity,

which is more closely associated with insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes than

overall adiposity (19). Additionally, Asians of both sexes have been shown to have

a higher percentage of body fat at any given BMI level compared with non-Hispanic

whites; this suggests differences in body composition that may contribute to variations

in diabetes prevalence (10).

Defining the Issue

The established definitions of at-risk BMI for overweight and obesity appear to be

inappropriate for defining diabetes risk in Asian Americans. Thus, there is a need

to examine the existing literature to determine what might constitute at-risk BMI

levels for Asian Americans. The clinical relevance is to clarify the use of BMI as

a simple initial screening tool to identify Asian Americans who may have diabetes

(diagnosis) or be at risk for future diabetes (to implement prevention measures).

Also of importance is the use of specific BMI cut points to identify Asian Americans

who are eligible for weight-reduction services or treatment reimbursable by payers.

Available data from Asia support the notion that Asians are already at risk for many

obesity-related disorders even if they do not reach the BMI values associated with

overweight or obesity in non-Asian populations (14). Population-wide weight gain is

occurring throughout Asia. This has been attributed to environmental influences such

as dietary changes and reductions in physical activity commonly associated with living

in a Western culture (17). However, the impact of actually living in a Western culture

may be different or more adverse than the effect of living in the native homeland

and experiencing some of the lifestyle features representative of a Western culture.

Rather than relying on hypothetical influences surmised from data from Asia, it is

better therefore to directly examine the relationship of BMI to metabolic disorders

such as type 2 diabetes among Asians living in the U.S. Although the U.S. Census has

historically combined Asians, Native Hawaiians, and other Pacific Islanders, there

are significant differences in physiology and body composition between Asians and

the other two groups, so this review will focus only on examining studies in Asian

Americans.

Asian American Studies of Type 2 Diabetes and Overweight/Obesity

Prospective cohort or longitudinal studies are the most suitable designs to measure

type 2 diabetes incidence and delineate the relationship between BMI and diabetes.

This research requires clinical ascertainment of BMI and nondiabetic status at baseline,

followed by periodic reascertainment for a defined follow-up period or until diabetes

is diagnosed. Glucose tolerance status should be evaluated by blood test, preferably

including a 2-h 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). This recommendation is based

on numerous studies, including research on Asian Americans, indicating that OGTT detects

a greater number of individuals with diabetes compared with fasting glucose criteria

(20–22). This type of longitudinal study design enables 1) identification of baseline

BMI values associated with increased diabetes risk over a defined follow-up and 2)

capture of BMI data at the earliest time point following diabetes diagnosis. The sensitivity

and specificity of BMI cut points can then be identified using analytic techniques

such as receiver operating characteristic curves or rate of misclassification.

Historically, such prospective cohort data are uncommon in Asian American populations.

The majority of peer-reviewed publications on diabetes among Asian Americans are cross-sectional

studies in which BMI, calculated from self-reported weight and height, and diabetes

status are assessed simultaneously. In 2004, data from the Behavioral Risk Factor

Surveillance System (BRFSS) showed that the odds of prevalent diabetes were 60% higher

for Asian Americans than non-Hispanic whites after adjusting for BMI, age, and sex

(23). The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS; 1997–2008 data) (24) found that

the odds of prevalent diabetes were 40% higher in Asian Americans relative to non-Hispanic

whites after adjusting for differences in age and sex. In fully adjusted logistic

regression models including an adjustment for BMI as a categorical variable (underweight/normal

weight: BMI <23 kg/m2, overweight: 23 ≤ BMI < 27.5 kg/m2, and obese: BMI ≥27.5 kg/m2),

Asian Americans remained 30–50% more likely to have diabetes than their non-Hispanic

white counterparts (24). Additionally, regional studies, such as the New York City

Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (25), have confirmed that Asian residents

in New York City had the highest levels of dysglycemia (diabetes and prediabetes combined)

of any race/ethnicity based on prior history or fasting glucose measurement. By disaggregating

subgroups from these studies, investigators found that South Asians consistently had

the highest diabetes prevalence compared with other Asian subgroups and non-Hispanic

whites (26). Although informative, these studies’ cross-sectional designs were unable

to identify BMI at the time of diabetes diagnosis thereby indicating minimum BMI cut

points when diabetes is newly diagnosed.

A systematic review by Staimez et al. (27) summarized findings from 97 publications

(1988–2009) on the prevalence of overweight, obesity, and diabetes among specific

Asian American subgroups, including Chinese, Filipinos, Koreans, South Asians, and

Vietnamese. Almost all the articles reviewed for this publication reported cross-sectional

data for the variables of interest, and only two provided longitudinal data that were

incorporated in the conclusion. These earlier studies reported tremendous heterogeneity

in diabetes prevalence, ranging from 3.9 to 32.9% in Asian Indians, 1.0–11.3% among

South Asians, 2.2–28.0% in Chinese, 3.7–30.9% among Filipinos, 5.3–15.6% in Vietnamese,

and 10.0–18.1% among Koreans (27). Similar heterogeneity was reported for obesity

prevalence. As the objectives, age and sex distribution, recruitment methods, and

ascertainment of BMI and diabetes varied broadly among these studies, it is not feasible

to use these data to identify BMI cut points for diabetes manifestation. To do this,

it is imperative to establish BMI levels that place populations at risk for diabetes

prior to diabetes diagnosis as weight loss may occur either with undiagnosed diabetes

or following diagnosis due to glycosuria or treatment with lifestyle intervention

or pharmacologic agents that promote weight loss.

Since publication of the article by Staimez et al. (27), prospective cohort studies

on diabetes incidence among Asians in North America (comprising the U.S. and Canada)

have been limited to just five prospective cohorts (based on a PubMed search of the

English literature published since 2009). Table 1 summarizes the prospective studies

that have reported incident diabetes rates in Asian American populations. We reviewed

these studies, based on whether data were analyzed by specific Asian ethnicity (disaggregated)

or not (aggregated).

Table 1

Prospective cohort studies (2009–2013) reporting incident diabetes in Asian American

populations

Reference

Study, location, and follow-up

Sample size

Mean age, years

BMI, kg/m2

Diabetes ascertainment method

Diabetes incidence

Aggregated data

Ma et al., 2012 (28)

Women’s Health Initiative (1993–2009)

Asian*: 4,190

Asian: 63.0 (7.5)

Asian: 24.8 (4.6)

Self-report: physician prescribed “pills or insulin shots for diabetes”

Cumulative incidence %

Black: 14,618

Black: 61.6 (7.1)

Black: 31.2 (6.7)

Asian: 10.6

Hispanic: 6,484

Hispanic: 60.2 (6.8)

Hispanic: 29.1 (5.8)

Black: 17.0

40 centers throughout the U.S.

White: 133,541

White: 63.6 (7.2)

White: 27.6 (5.8)

Hispanic: 14.6

Follow-up: 10.4 years

Incidence rate (per 1,000 person-years)

Asian: 1.13

Black: 1.87

Hispanic: 1.67

White: 0.82

Disaggregated data

Karter et al., 2013 (29)

DISTANCE studyNorthern California Mean follow-up: 1 year

1,704,363 Kaiser Permanente Northern California members with known ethnicity

Filipino: 49.1 (16.2)

Mean BMI at baseline

Based on medical records: ICD-9: 250 (inpatient or two or more outpatient diagnoses)Either

FPG ≥126 mg/dL; random or postchallenge glucose ≥200 mg/dLPrescription for insulin

or oral antihyperglycemic medications

Age- and sex-adjusted prevalence %

Filipino: 82,781

Chinese: 51.6 (16.8)

Filipino: 26.6 (4.7)

Filipino: 16.1

Chinese: 68,831

Japanese: 58.7 (17.7)

South Asian: 26.4 (4.7)

South Asian: 15.9

Japanese: 16,032

South Asian: 43.4 (15.0)

SE Asian: 26.4 (5.2)

SE Asian: 10.5 Japanese: 10.3 Korean: 9.9 Vietnamese: 9.9 Chinese: 8.2 White: 7.3

South Asian: 6,768

SE Asian: 37.7 (12.2)

Japanese: 25.4 (4.9)

SE Asian: 1,876

Korean: 49.6 (15.7)

Korean: 24.9 (4.2)

Korean: 1,130

Vietnamese: 39.5 (11.6)

Vietnamese: 23.9 (4.1)

Vietnamese: 1,671

White: 53.6 (18.0)

Chinese: 24.2 (4.0)

White: 968,943

Latino: 44.8 (16.5)

White: 28.3 (6.4)

Latino: 253,821

Black: 48.8 (17.5)

Black: 30.9 (7.5)

Latino: 14.0

Black: 135,934

Latino: 29.7 (6.4)

Black: 13.7

Incidence rate (per 1,000 person-years)

Korean: 20.3

South Asian: 17.2

Filipino: 14.7

SE Asian: 11.4

Japanese: 7.5

Chinese: 6.5

Vietnamese: 4.6

White: 6.3

Latino: 11.2

Black: 11.2

Wander et al., 2013 (36)

Japanese-American Community Diabetes Study Seattle, WA

421 Japanese Americans, 54% male

51.4 years (34.0–75.1)

Baseline

2-h 75-g OGTT

Cumulative incidence

Mean: 24.1 (range 16.6–36.9)

20.4%

After 5 years

5-year incidence

Incident T2D: 24.9

9.3%

Nondiabetic: 24.0

10-year incidence

Follow-up: 10 years

After 10 years

17.6%

Incident T2D: 25.4

Nondiabetic: 23.8

Chiu et al., 2011 (31)

Multiethnic Cohort Ontario Study

South Asian: 1,001

South Asian: 42 (36–49)

Self-reported BMI at baseline

Linkage with Ontario diabetes database (from multiple administrative sources)

Incidence rate (per 1,000 person-years)

Ontario, Canada

Chinese: 866

Chinese: 42 (36–50)

South Asian: 24.6 (22–27)

Baseline BMI 18.5–23

Mean follow-up: 12.8 years (1996–2009)

White: 57,210

White: 46 (38–57)

Chinese: 22.6 (20.0–24.0)

White: 3.1 (2.7–3.6)

Black: 747

Black: 42 (36–51)

White: 26.1 (23.0–28.0)

South Asian: 11.6 (6.0–17.8)

Black: 26.1 (23.0–28.0)

Chinese: 3.7 (1.1–6.4)

Black: 7.3 (1.1–16.9)

Baseline BMI 23–27.5

White: 6.9 (6.4–7.6)

South Asian: 20.2 (13.1–27.8)

Chinese: 16.8 (8.4–25.2)

Black: 14.1 (8.6–20.2)

Baseline BMI ≥27.5

White: 19.0 (17.9–20.0)

South Asian: 44.9 (28.1–63.9)

Chinese: 30.9 (10.9–52.6)

Black: 28.9 (17.0–42.9)

Maskarinec et al., 2009 (32)

Hawaii Component of the Multiethnic Cohort

Caucasian: 35,042

% in age category

% in BMI category

Insurance data, blood test

Incidence rate (per 1,000 person-years)

Hawaii

Japanese: 44,513

Japanese men

Japanese men

White: 5.8 (5.0–6.6)

Mean follow-up: 12 years

Hawaiian: 14,346

<55: 29.6%

BMI <22: 18.5%

Japanese: 12.5 (11.4–13.5)

Other: 9,997

55–64: 27.5%

BMI 22–24.9: 37.2%

Hawaiian: 15.5 (13.3–17.6)

≥65: 42.9%

BMI 25–29.9: 37.2%

Other: 12.2 (9.9–14.4)

Japanese women

BMI ≥30: 7.2%

<55: 29.9%

Japanese women

55–64: 29.6%

BMI <22: 41.5%

≥65: 40.5%

BMI 22–24.9: 29.7%

White men

BMI 25–29.9: 22.6%

<55: 42.6%

BMI ≥30: 6.2%

55–64: 27.6%

White men

≥65: 29.8%

BMI <22.0: 13.8%

White women

BMI 22.0–24.9: 31.6%

<55: 44.4%

BMI 25.0–29.9: 40.7%

55–64: 26.9%

BMI ≥30.0: 13.9%

≥65: 28.7%

White women

BMI <22: 33.2%

BMI 22.0–24.9: 27.4%

BMI 25.0–29.9: 25.2%

BMI ≥30.0: 14.1%

Data are mean (SD) unless otherwise indicated. FPG, fasting plasma glucose; SE, Southeast;

T2D, type 2 diabetes.

*

Self-reported Chinese, Indo-Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Pacific Islander, and Vietnamese.

Aggregated Data

The Women’s Health Initiative (28) enrolled postmenopausal women aged 50–79 years

from 40 clinical centers nationwide from 1993 to 1998 and followed them for 10.4 years.

Participants included 14,618 African American, 133,541 non-Hispanic white, 6,484 Latino/Hispanic,

and 4,190 Asian American women. Although the Asian American women self-reported as

being Chinese, Indo-Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Pacific Islander, or Vietnamese, data

were not disaggregated into these separate ethnic groups.

Baseline BMI was measured at the clinic visit, and incident diabetes was based on

self-reported affirmative responses that a doctor prescribed “pills for diabetes”

or “insulin shots for diabetes, collected at annual follow-up visits.” As shown in

Table 1, mean baseline BMI among Asians was 24.8 kg/m2, cumulative diabetes incidence

was 10.6%, and the incidence rate was 1.13 per 100 person-years. Compared with non-Hispanic

whites, Asian Americans had the highest risk for incident diabetes after adjusting

for age, study arm, baseline BMI, physical activity, dietary quality, smoking status,

family history of diabetes, and educational attainment (hazard ratio [HR] 1.86 [95%

CI 1.68−2.06]).

Disaggregated Data

The Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE) from Kaiser Permanente Northern

California (29), a large integrated health-delivery system, was a prospective study

in which enrolled adults were followed for 1 year. Data were disaggregated into 12

single racial/ethnic groups, including 7 distinct Asian subgroups. Of the 1,912,916

individuals without prevalent diabetes in 2010, a total of 15,357 incident diabetes

cases were identified in the following year. The incidence rates for diabetes were

highest among Pacific Islanders (19.9/1,000 person-years), followed by South Asians

(17.2), and Filipinos (14.7). The mean BMI at diagnosis among those who developed

incident diabetes was 27.2 kg/m2 in Chinese, 28.7 kg/m2 in Japanese, 29.0 kg/m2 in

Filipinos, and 29.6 kg/m2 in South Asians, compared with a mean BMI of 33.4 kg/m2

in non-Hispanic whites, 35.5 kg/m2 in African Americans, and 34.3 kg/m2 in Latinos

(A. Karter, personal communication). There was a consistent pattern across all racial/ethnic

groups of lower BMIs among individuals with prevalent diabetes when compared with

those with incident diabetes. Those with normal glucose levels had even lower BMI

compared with prevalent or incident diabetes cases. However, in other prospective

studies discussed in this section, the BMI used for analyses was collected at baseline

and may have preceded diabetes diagnosis by 5–10 years, depending on the duration

of study follow-up (28,30–32).

The Seattle Japanese-American Community Diabetes Study, conducted in King County,

WA, was a community-based prospective study of type 2 diabetes in second- and third-generation

adults of 100% Japanese ancestry in Seattle. This research has yielded many publications

on the relationship between body weight and body fat distribution, as well as the

prevalence and incidence of type 2 diabetes (33). Although publications from the Japanese-American

Community Diabetes Study have repeatedly shown the importance of central and especially

visceral fat as a risk factor for coronary heart disease (20), hypertension (34),

impaired glucose tolerance (35), type 2 diabetes (36), metabolic syndrome (37), and

insulin resistance (11), investigators also identified a relationship between BMI

and diabetes incidence when BMI was the sole measurement of body fat examined (38).

Among 466 nondiabetic Japanese Americans with a mean BMI 24.1 ± 0.2 kg/m2 at baseline,

49 developed diabetes at 5 years, based on a 75-g OGTT (30). Study participants who

developed diabetes had a mean BMI of 24.9 ± 0.5 kg/m2, while those remaining nondiabetic

had a mean BMI of 24.0 ± 0.2 kg/m2. These differences approached statistical significance

(P = 0.068). However, among participants aged ≤55 years, men who developed diabetes

were heavier than nondiabetic individuals, with mean respective BMIs of 28.7 ± 0.8

and 25.1 ± 0.3 kg/m2 (P < 0.001), while the difference in women (25.1 ± 1.2 and 22.8

± 0.3 kg/m2) did not reach statistical significance. Among men or women aged >55 years,

incident diabetes was not associated with baseline BMI. In participants ≤55 years

of age, the 5-year relative risk of diabetes associated with BMI was 26.5 (95% CI

3.4−204) but was 0.8 (95% CI 0.4−1.7) for those >55 years of age. Thus in this analysis

at 5 years, BMI predicted risk for diabetes in Japanese Americans ≤55 years of age

but not in those >55 years of age.

In a subsequent analysis of 424 initially nondiabetic Japanese Americans who were

followed for additional 5 years (total of 10 years), 74 developed diabetes (36). Those

developing diabetes had a mean BMI of 25.4 ± 3.7 kg/m2, while those who remained nondiabetic

had a mean BMI of 23.8 ± 3.1 kg/m2. The odds of incident diabetes for a 1 SD increase

in BMI were 1.57 (95% CI 1.23−2.02). Thus, these two studies indicate that BMI is

a significant risk factor for incident diabetes in Japanese Americans and that the

BMI levels at which diabetes develops are quite low. However, neither report provided

an inflection point for BMI at which risk was significantly increased.

A multiethnic cohort study identified nondiabetic adults in Ontario, Canada, using

Statistics Canada’s 1996 National Population Health Survey and the Canadian Community

Health Survey (31). Survey participants living in Ontario, aged ≥30 years at the time

of survey, and who self-reported as South Asian (n = 1,001) or Chinese (n = 866) comprised

the Asian cohorts and were followed for a median of 6 years. Also included were blacks

(n = 747) and non-Hispanic whites (n = 57,210). BMI was based on self-reported weight

and height at baseline, and incident diabetes cases were ascertained through record

linkage with the population-based Ontario Diabetes Database using a validated administrative

data algorithm. Participants were followed from the survey interview date to the date

of diabetes diagnosis, death, or at the end of the study. At baseline, mean BMI was

24.6 kg/m2 among South Asians, 22.6 kg/m2 among Chinese, 26.1 kg/m2 among blacks,

and 26.1 kg/m2 among non-Hispanic whites. Researchers found that incident diabetes

risk, adjusted for age, sex, sociodemographic characteristics, and BMI, was significantly

higher for South Asians (20.8/1,000 person-years; HR 3.40), blacks (16.3/1,000; 1.99),

and Chinese (9.3/1,000; 1.87), compared with non-Hispanic whites (9.5/1,000). The

BMI cutoff value at which diabetes incidence was equivalent to BMI 30 kg/m2 for non-Hispanic

whites was estimated at 24 kg/m2 for South Asians, 25 kg/m2 for Chinese, and 26 kg/m2

for blacks. Additionally, the median age at diagnosis was younger for South Asians

(49 years) and Chinese (55 years) compared with blacks (57 years) and non-Hispanic

whites (58 years).

Last, the Multiethnic Cohort (32) in Hawaii included non-Hispanic whites, Native Hawaiians,

and Japanese Americans. The Hawaii data from this cohort were linked to two diabetes

care registries (Blue Cross/Blue Shield and Kaiser Permanente Hawaii). Incident type

2 diabetes was identified by self-report of medical conditions between 1999 and 2003,

a medication questionnaire, and linkage with health insurance plans in 2007. Native

Hawaiians had the highest incidence (15.5/1,000 person-years), followed by Japanese

Americans (12.5/1,000), while non-Hispanic whites had the lowest incidence (5.8 cases/1,000).

The authors compared the HR of incident diabetes at different BMI cut points for each

racial/ethnic group and found that Japanese Americans had a significantly higher incidence

of diabetes at BMI 22.0–24.9 kg/m2 than Hawaiians or non-Hispanic whites. Diabetes

risk for Japanese Americans was higher than for non-Hispanic whites at all BMI levels.

Even at BMI cut points of <22 kg/m2 and 22.0−24.9 kg/m2, respectively, HRs were higher

among Japanese Americans compared with non-Hispanic whites at BMI cut points of 25.0−29.9

kg/m2.

New Cross-sectional Analysis

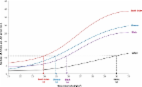

Most recently, in an effort to ascertain the lowest BMI cut point that might be practical

for identifying Asian American adults (aged ≥45 years) with previously undiagnosed

type 2 diabetes, a group of investigators presented a new analysis at the 2014 Scientific

Sessions of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) based on combined data from four

cohort studies (39).The data set included participants without a prior diabetes diagnosis,

aged ≥45 years, with no non-Asian admixture. Participant data were obtained from the

University of California San Diego Filipino Health Study, San Diego, CA (n = 421);

North Kohala Study, Hawaii, HI (n = 115 Filipinos, 129 Japanese, 18 other Asian);

Seattle Japanese-American Community Diabetes Study, Seattle, WA (n = 371); and the

Mediators of Atherosclerosis in South Asians Living in America (MASALA), San Francisco,

CA, and Chicago, IL (n = 609). All 1,663 participants underwent 2-h 75-g OGTT, and

diabetes diagnosis was based on ADA 2014 criteria (40). In the total sample, a BMI

≥26 kg/m2 cut point had the lowest misclassification rate (false-positive + false-negative

rates) and highest Youden’s index (sensitivity + specificity −1). Sensitivity approximated

specificity at BMI ≥25.4 kg/m2; however, limiting screening at BMI ≥25 kg/m2 would

miss 36% of Asian Americans with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. In the same study,

Araneta et al. (39) found that screening Asian Americans at a BMI cut point of ≥23.5

kg/m2 identified approximately 80% of those with undiagnosed type 2 diabetes. Among

Japanese Americans, lowering the BMI screening cut point to ≥22.8 kg/m2 achieved 80%

sensitivity. The same study also showed that limiting screening to HbA1c ≥6.5% fails

to identify almost half of Asian Americans with diabetes and 44% who had isolated

postchallenge hyperglycemia would be missed without an OGTT.

Conclusions

This comprehensive review and analysis of the association between BMI and diabetes

in Asian Americans illustrates that Asian Americans have a higher prevalence of type

2 diabetes at relatively lower BMI cut points than whites. Given that established

BMI cut points indicating elevated diabetes risk are inappropriate for Asian Americans,

establishing a specific BMI cut point to identify Asian Americans with or at risk

for future diabetes would be beneficial to the potential health of millions of Asian

American individuals.

Generally, the rationale behind the conventional BMI cut point has been the observation

that overweight and obese adults (18 years of age or older) with a BMI of ≥25 kg/m2

have increased risks of both morbidity and mortality. Adults who meet or exceed the

25 kg/m2 BMI threshold are at increased risk of developing coronary heart disease,

hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, type 2 diabetes, and other diseases, in addition

to showing increases in mortality (41). However, while the studies reviewed herein

do indicate increased diabetes prevalence among Asian Americans with BMIs below the

25 kg/m2 threshold, a recent study (42) found no evidence to suggest an increased

risk of total mortality among Asian Americans within the BMI range of 20 to <25 kg/m2.

Therefore, it is important to note that the aim of this position statement is not

to redefine BMI cut points that constitute overweight and obesity thresholds as they

relate to mortality or morbidity in Asian Americans. Instead, the intent is to clarify

how to use BMI as a simple initial screening tool to identify Asian Americans who

may have diabetes or be at risk for future diabetes. The question being considered

is the most appropriate BMI cut point indicative of elevated risk of diabetes in Asian

Americans. Historically, there has been a general acknowledgment that a BMI cutoff

point lower than 25 kg/m2 would increase the likelihood of identifying diabetes or

diabetes risk in Asians. Thus in the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP), a BMI value

of 22 kg/m2 was selected as the eligibility BMI for Asians (43). The 2014 ADA “Standards

of Medical Care in Diabetes” (40) indicates that there is compelling evidence that

lower BMI cut points, specifically BMI cutoff value of 24 kg/m2 in South Asians and

25 kg/m2 in Chinese, denote increased diabetes risk in some racial and ethnic groups,

although the ADA Standards fall short of identifying an exact cut point. However in

2000, a group cosponsored jointly by the Regional Office for the Western Pacific (WPRO)

of the World Health Organization, the International Association for the Study of Obesity,

and the International Obesity Task Force published in an extensive monograph a recommendation

that the BMI value to denote overweight in Asians should be ≥23 kg/m2 and ≥25 kg/m2

for obesity (44). Subsequently, the World Health Organization consultation group identified

potential public health action points along the BMI continuum ranging from 23.0 to

27.5 kg/m2 and proposed that each country make decisions regarding the definitions

of increased risk for its population (45). They did not identify an exact cut point.

In addition, some Asian countries have taken steps to set new BMI obesity cut points

for their populations. In 1992, the Japan Society for the Study of Obesity (JASSO)

decided to define BMI ≥25 kg/m2 as obesity (46). In China, a BMI of 24 kg/m2 was found

to have the best sensitivity and specificity for risk-factor identification and was

recommended as the cutoff point for overweight. A BMI of 28 kg/m2 was found to identify

risk factors with specificity approximately 90% and was recommended as the cutoff

point for obesity (47). Likewise, the diagnostic cutoff for overweight BMI in India

(48) is 23 kg/m2.

Determining the optimal BMI cut point for identifying Asian Americans at elevated

risk for diabetes is complex. There is tremendous heterogeneity among the Asian American

subgroups. For example, data from the DISTANCE study might suggest a conventional

BMI cut point of 25 kg/m2 as an acceptable threshold (29), especially for South Asians

and Southeast Asians. In contrast, the Women’s Health Initiative (28), the Seattle

Japanese-American Community Diabetes Study (36), the multiethnic cohort study from

Canada (31), and the Multiethnic Cohort in Hawaii (32) would lend support to lowering

the BMI cut point, especially for East Asians (Chinese and Japanese).

In light of the diabetes epidemic, there is an urgent need to increase early detection

and activate the at-risk public toward diabetes prevention. Adopting a single lower

and uniform BMI cut point for Asian Americans would serve to increase opportunities

for education, intervention, behavior and lifestyle change, and diagnosis. In support

of this approach, data from Araneta et al. (39) suggest that for diabetes screening

purposes BMI cut points with a sensitivity of 80% fall consistently between 23–24

kg/m2 for nearly all Asian American subgroups (with levels slightly lower for Japanese).

This makes a rounded cut point of 23 kg/m2 practical. In determining a single BMI

cut point, it is important to balance sensitivity and specificity so as to provide

a valuable screening tool without numerous false positives. Furthermore, for a screening

tool to be most valuable, it must be at least as useful as other commonly available

tools. A BMI cut point of 23 kg/m2 will have greater sensitivity than the ADA general

screening questionnaire’s (ADA Type 2 Diabetes Risk Test) sensitivity of 70–80% (49).

An argument can be made to push the BMI cut point to lower than 23 kg/m2 in favor

of even further increased sensitivity. However, this would lead to an unacceptably

low specificity (13.1%) (39).

The authors of this position statement propose that the analysis of BMI and diabetes

in Asian Americans and subsequent recommendation of an Asian American−specific BMI

cut point of 23 kg/m2 for diabetes screening in the U.S. have the advantage of being

predicated on available data for Asian Americans, not Asian country data. In this

way, this recommendation takes into consideration not only genetic and physiologic

factors but also environmental and lifestyle context. Further, it is based on a comprehensive

review of available literature with focus on longitudinal studies and includes data

from several large Asian American subgroups.

However, the analysis is limited in several ways. First, no uniform method of diagnosis

was used in the studies upon which this recommendation is based. Diagnostic methods

ranged from medication usage data, self-report, HbA1c, fasting blood glucose, and

OGTT. Studies using diagnostic methods other than OGTT might have understated diabetes

prevalence (20–22,39). Second, some studies were not based on BMI data available at

the time of incident diabetes. Rather, most studies reported the association between

baseline BMI and diabetes diagnosis, with these measurements as much as 5–10 years

apart in some instances. Therefore, these data do not accurately reflect the relationship

of BMI to diabetes diagnosis at the time of diagnosis. Third, the number of robust

studies is limited. Additional research will help to further elucidate current findings

on the relationship between BMI and incident diabetes in Asian Americans. Fourth,

while some data exist for several Asian ethnic subgroups, insufficient disaggregated

data are available for many of the Asian ethnic groups that comprise this very heterogeneous

population.

Much is known about how to prevent diabetes for those at risk (primary prevention)

and about how to prevent or reduce complications in those with diabetes (secondary

prevention). Diabetes is no longer the same life-threatening, life-limiting condition

it was a century or even several decades ago. However, without increased prevention

and early diagnosis the benefits of these strategies will not be fully realized. Because

Asian Americans’ risk for diabetes is under-recognized based on the existing BMI criteria,

this population may not be afforded the same opportunity as others for increased prevention

and early diagnosis. It is imperative to better screen and diagnose America’s fastest-growing

ethnic group based on the BMI cut point that more appropriately applies to them. While

more research is needed to identify better risk markers than BMI and future research

efforts will undoubtedly bring us closer to understanding the metabolic profiles of

specific ethnic subgroups, with the subsequent development of appropriate personalized

medicine, there is an urgent need for action now, even in the absence of perfect data.

ADA Recommendation

Testing for diabetes should be considered for all Asian American adults who present

with a BMI of ≥23 kg/m2.

Related collections

Most cited references32

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Waist circumference and abdominal sagittal diameter: best simple anthropometric indexes of abdominal visceral adipose tissue accumulation and related cardiovascular risk in men and women.

M Pouliot, J P Després, S Lemieux … (1994)

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Deriving Ethnic-Specific BMI Cutoff Points for Assessing Diabetes Risk

Maria Chiu, Peter C Austin, Douglas G. Manuel … (2011)

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Impaired glucose tolerance and impaired fasting glycaemia: the current status on definition and intervention.

Daniel Shaw, K Alberti, N Unwin … (2002)