- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Built Environment and SARS-CoV-2 Transmission in Long-Term Care Facilities: Cross-Sectional Survey and Data Linkage

Read this article at

Abstract

Objectives

To describe the built environment in long-term care facilities (LTCF) and its association with introduction and transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Setting and Participants

LTCFs in England caring for adults ≥65 years old, participating in the VIVALDI study (ISRCTN14447421) were eligible. Data were included from residents and staff.

Methods

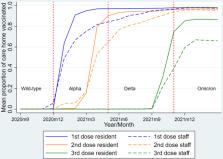

Cross-sectional survey of the LTCF built environment with linkage to routinely collected asymptomatic and symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 testing and vaccination data between September 1, 2020, and March 31, 2022. We used individual and LTCF level Poisson and Negative Binomial regression models to identify risk factors for 4 outcomes: incidence rate of resident infections and outbreaks, outbreak size, and duration. We considered interactions with variant transmissibility (pre vs post Omicron dominance).

Results

A total of 134 of 151 (88.7%) LTCFs participated in the survey, contributing data for 13,010 residents and 17,766 staff. After adjustment and stratification, outbreak incidence (measuring infection introduction) was only associated with SARS-CoV-2 incidence in the community [incidence rate ratio (IRR) for high vs low incidence, 2.84; 95% CI, 1.85–4.36]. Characteristics of the built environment were associated with transmission outcomes and differed by variant transmissibility. For resident infection incidence, factors included number of storeys (0.64; 0.43–0.97) and bedrooms (1.04; 1.02–1.06), and purpose-built vs converted buildings (1.99; 1.08–3.69). Air quality was associated with outbreak size (dry vs just right 1.46; 1.00–2.13). Funding model (0.99; 0.99–1.00), crowding (0.98; 0.96–0.99), and bedroom temperature (1.15; 1.01–1.32) were associated with outbreak duration.

Conclusions and Implications

We describe previously undocumented diversity in LTCF built environments. LTCFs have limited opportunities to prevent SARS-CoV-2 introduction, which was only driven by community incidence. However, adjusting the built environment, for example by isolating infected residents or improving airflow, may reduce transmission, although data quality was limited by subjectivity. Identifying LTCF built environment modifications that prevent infection transmission should be a research priority.

Related collections

Most cited references29

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) Statement

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Rapid epidemic expansion of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant in southern Africa

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found