INTRODUCTION

In June 2015, the Committee on Publication Ethics, the Directory of Open Access Journals, the Open Access Scholarly Publishers Association and the World Association of Medical Editors updated their joint statement, originally published in 2013: the Principles of Transparency and Best Practice in Scholarly Publishing [1]. These principles were to a considerable extent derived from the criteria for the admission of journals into DOAJ that were expanded, updated and put into practice in March 2014 [2].

In addition, 50 Science Europe members issued a statement in April [3] this year on four new guidelines for publishers when providing payments/subsidies for Open Access venues. The first principle states that journals must be listed in DOAJ, Web of Science, Scopus or PubMed. The second principle corresponds to one of the criteria that DOAJ uses for the Seal: authors must hold the copyright of their publication with no restrictions. Both these statements are a milestone on a long road that started in 2003 when the Directory of Open Access Journals was founded with the objective of providing a service for indexing and accessing quality open access journals.

Open Access to scholarly publications has grown and matured and DOAJ has become more firmly rooted in the heart of open access research publishing than ever. It is hard to believe that, since DOAJ launched on its new platform at the end of 2012, the database can have changed and matured so much in so little time. DOAJ has taken a quantum leap in terms of functionality, data quality and standardisation. With its technical partner, Cottage Labs, DOAJ has no less than 13 large or extra large developments projects under its belt and three extra-large projects in progress now. Every single project is paid using funding from donations from our members and sponsors. Two of the projects in progress will prove to be the most exciting and rewarding yet. (Even though the platform migration gave us plenty of large and complex projects to get our teeth into, those were done out of necessity: stabilising, future-proofing, capacity building and cleaning).

A POTTED HISTORY OF DOAJ [4]

Originally, the criteria for admission were not as strict as they are today. The original application form captured the basic minimum that a reviewer working for DOAJ would need to know to be able to locate the journal online, contact someone about it and make investigations. The initial form had only six questions but if the application was deemed to be from a real journal, a further form was sent requiring much more information. Reviewers were still expected to find much of the information themselves.

“At the time, it was impossible to foresee how fast open access would be adopted into mainstream academic publishing, but of course, this was what we were pushing for. The rate of growth of open access publishing was an almost intangible concept back in 2003. We had the luxury of time on our side. For every application we received, we would go and hunt down all the markers of quality and best practice by hand, without even asking the publisher to provide them”, says Lars Bjørnshauge, DOAJ's founder.

The DOAJ was launched at the First Nordic Conference on Scholarly Communication [5] on the principle that the creation of a comprehensible service that listed quality-controlled, peer-reviewed open access journals would be beneficial for the whole scholarly community. At launch, the directory consisted of 300 journals applying immediate open access to their full texts, and in 2004 a searchable article index was added. By 2006 the directory consisted of more than 2000 titles and the service was expanded to include extra fields such as Article Processing Charges (APCs), added because charging publication fees for open access articles had become an important financial model. The DOAJ membership programme was launched in 2007 to help the service to survive the transformation from project into an established service. In April 2008 the Directory consisted of more than 3000 titles at which time DOAJ started insisting on the use of Creative Commons licences as a best practice for open access journals.

Between 2008 and 2011, DOAJ became an important source of data for research, so DOAJ published a breakdown of the number of open access journals added per year, by country. This exposed how the United States and Brazil had risen very quickly to the top of the list. The development of the SciELO umbrella helped the relatively fast development of Open Access in South America [6] and, along with projects like Redalyc, established open access publishing firmly in the infrastructure. However, activities for promoting open access in Asia also flourished and people caught on to the business potential of open access; the number of DOAJ-listed titles from Asia grew from 10% to 15% in only two years. Through activities run by INASP, a number of Asian countries such as Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Vietnam and the Philippines were able to publish their journals in the Journals OnLine project (JOL) where INASP gathers open access journals from these countries in different lists [7]. In January 2013, DOAJ moved from Lund University to its current management company, Infrastructure Services for Open Access [8]. This move set in motion a series of substantial changes that have seen DOAJ develop from a small indexing project to a well-known and reputable Directory that is, today, the most important reference source in the world for peer-reviewed open access journals.

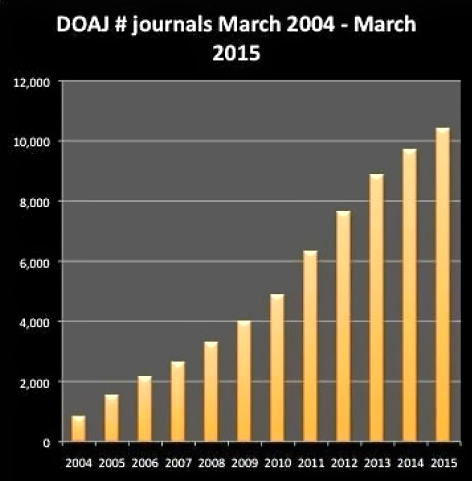

The number of open access journals in DOAJ has increased from the original 300 listed in 2003 to more than 10,000 in 2015. As well as this accelerated growth, the proliferation of funder open access policies and publication funds at universities created demands for more granular information about the journals in the Directory. (For instance to determine an author's eligibility for support paying APCs to specific journals.) This called for a more stringent set of selection criteria that met the expectations of stakeholders, that on their own proactively encouraged best practice and transparency, and rose to the challenges of the maturing open access market with its rapidly increasing number of journals.

The open access landscape has changed tremendously since 2003.

DOAJ IN NUMBERS/STATISTICS

DOAJ handles such an astonishing number of applications for journals wishing to be indexed that it is becomes difficult to believe that there are so many open access journals in the world. For example, Brazil alone has 1012 journals indexed in DOAJ and a further 280 applications are in progress. Two hundred and sixty-eight applications from Brazil have been rejected since March 2014. Brazil is only one of the 135 countries that have journals indexed in DOAJ, but 56 countries have 10 journals or fewer. USA, Brazil, United Kingdom and Spain have the most journals indexed in DOAJ, accounting for 3366 journals. United States, India, Brazil and United Kingdom have the most records in the Applications database, totaling 5746 applications that are pending, in progress, accepted or rejected. There are over 4100 records in the applications database that require attention from the DOAJ Team.

We use a triage function to eliminate incomplete, duplicate or spam submissions, and, to ensure complete objectivity, every complete and viable application is then seen by three individuals: a Managing Editor, an Editor and an Associate Editor. It is the Associate Editor who does the bulk of the review work, checking the application for correctness and querying the Journal Contact, but once complete an Editor reviews the work, makes a recommendation and finally passes the application to a Managing Editor.

DOAJ receives approximately 80 new applications every week of the year, with only marginal seasonal variation. From Google Analytics, we know that 95% of all people who visit the application form never make it through to the Thank You page, that is to say, to completing and submitting a successful application. Of those applications which are successful, not all make it through the first round of triage: about 5–7% get rejected immediately because they are duplicate submissions, are missing a registered ISSN, are incomplete or are just spam! (It is incredible to think that purveyors of fake, luxury brand sunglasses will complete a 54-question application form in the chance that their product might get a listing on the DOAJ web site!)

Since DOAJ raised its entrance bar [2] in March 2014, it has rejected about 3500 applications, accepted 1910 and has a further 1900 being processed.

In terms of traffic, DOAJ has had over 2.5 million users in the last year, 75% of which are new visitors [9]. This is a 25% increase on the previous year. This increase is partly due to better indexing in the major search engines and partly due to DOAJ reinstating its OpenURL feature, reconnecting it back to large third-party databases such as Serial Solutions and EBSCO. (Between them, these two services account for 30% of all traffic referred to DOAJ in any given month.)

DIFFERENT INTERPRETATIONS OF “OPEN ACCESS”

With the increase in the number of journals, the number of interpretations of the term "open access" used by journals and publishers has risen simultaneously. The 2002 and 2010 BOA I definitions of Open Access [10] clearly state that

By “open access” to [peer-reviewed research literature], we mean its free availability on the public internet, permitting any users to read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of these articles, crawl them for indexing, pass them as data to software, or use them for any other lawful purpose, without financial, legal, or technical barriers other than those inseparable from gaining access to the internet itself. The only constraint on reproduction and distribution, and the only role for copyright in this domain, should be to give authors control over the integrity of their work and the right to be properly acknowledged and cited.

Many open access publishers still limit the use of open access publications to free reading and use custom copyright transfer agreements and restrict author rights. Most often, however, publishers limit the rights of authors by making them sign exclusive publishing agreements where the authors sign away their publishing rights or where copyright is left with the author, but the publisher claims the commercial rights.

These issues and many others are addressed by the latest set of acceptance criteria developed by DOAJ.

But first, let us start with the reason why DOAJ only accepts full open access journals and not the so-called “hybrid” journals where only part of the content is made available as open access.

THE CASE OF HYBRID JOURNALS

Why doesn't DOAJ index hybrid journals? After all, they play a role in open access publishing and are often journals with that traditional merit of ‘high prestige’. Those journals are often linked to publishers of reputation and even quality; indeed, they have become the “traditional” publisher's answer to getting a foot into the open access market.

Despite evidence on the internet to the contrary (do a search on “Directory of Open Access and Hybrid Journals”), DOAJ has never indexed hybrid journals. DOAJ was set up to list journals that were not based on a subscription model in any way.

Publishers argue that the hybrid model is just a transition state on the way to full open access but of this we are doubtful. Some see hybrid journals as means of allowing publishers to generate income from the payments of APCs on top of subscription revenues, resulting in the so-called “double dipping”. Publishers say that subscription rates are adjusted depending on the percentage of open access content, but lack of transparency on the breakdown of publishing revenues makes it difficult to provide strong evidence for this. Some publishers have recently launched new offsetting models where payments for hybrid open access and access to already-published content is an integrated package. It remains to be seen whether these inventions will do much in the way of promoting open access.

THE CASE OF QUESTIONABLE PUBLISHERS

An additional phenomenon that has been causing concern during recent years is unethical “publishers” trying to exploit the APC business model (another common business model in open access publishing is subsidised journals supported by funders, universities, etc. – in fact most open access journals operate on this model, although most articles published in open access journals are based on APC payments) [11]. These questionable publishers (as we prefer to label them) are exploiting the potentially lower entrance to the journal market based on the payments of APCs. Under the traditional subscription model, publishers cannot set up so easily publishing enterprises and launch journals in huge numbers overnight. A generic questionable publisher might have 20–30 journals all launched on the same day.

Questionable publishers profit on the publish and perish syndrome and are targeting primarily authors from developing countries [12], who are eager to be published in “international” journals because of the pay-off in terms of promotion, tenure and often cash and traditionally have experienced obstacles in being published in the North American/Western European journals because of the bias governing the selection process for content in these journals. Add to this the fact that the Western system of scholarly publishing often stigmatises developing country research as “local, regional” rather than “international”, and you can start to understand why questionable publishers have such easy prey. When the doors are closed and the entrance is blocked for developing country authors, it becomes attractive to publish in the aggressively marketed “journals” from questionable publishers. In addition, and this is true for authors from all parts of the globe and from countries of every economic rating, many researchers do not have the experience or information to hand to enable them to determine whether a journal is a reputable journal or not.

DOAJ is responding to the issue of questionable publishers, not only by applying tougher and more detailed inclusion criteria, but by means of collaboration with other organisations to fight this abuse. The earlier mentioned Principles of Transparency and Best Practice and the recently launched ThinkCheckSubmit campaign, empowering researchers to make more informed decisions before they submit their work to journals, are both examples of such activities.

DOAJ'S NEW CRITERIA

Since they were released for public comment before their implementation, the DOAJ criteria have attracted a lot of comment and attention. Some of that was received through the public consultation, the feedback from which was adopted into the criteria themselves, and some of it has been through the reuse, adoption or absorption of the criteria into other organisations’ working practices. For example: the Principles of Best Practice and Transparency used DOAJ's criteria as a starting point and in July 2015, Scopus (owned by Elsevier) started flagging Open Access journals listed in their database using DOAJ indexing as one of their criteria [13]. It is imperative that the criteria do not exist as a static set of rules but are able to adapt and grow to continue to accurately reflect the state of open access publishing. To that effect, they will occasionally be updated and publishers will be invited to update their entries accordingly. New standards and best practices will be included and, as the community devises ways to combat questionable publishers, those tools will be included as well.

The new DOAJ criteria are divided into five groups: (1) Basic Journal Information, (2) Quality and Transparency of the Editorial Process, (3) Openness of the journal, (4) Content Licensing and (5) Copyright issues.

In addition DOAJ selected seven criteria where journals that meet these requirements get the DOAJ Seal for excellent levels of open access, adherence to Best Practice and high publishing standards. It is important to note that these are extra criteria not required for acceptance into DOAJ.

Basic journal information

Concerning basic journal information we require journals to have a dedicated website with local content, one PDF per article and direct links to all the relevant information for that journal (like information for authors, copyright, licensing). We require an active, physical address where the publisher carries out their publishing operations (not an address registered through an agent) and a dedicated email address from the journal (e.g. not info@journal.com or editor@yahoo.com)

Of particular importance is information about the ownership and/or management of a journal, which must be clearly indicated on the journal's web site. Publishers shall not use organisational or journal names that would mislead potential authors and editors about the nature of the journal's owner. Also displaying fake impact factors on a home page is strongly discouraged and DOAJ perceives this as an attempt to lure authors in a dishonest way.

Openness of the journal and quality and transparency of the editorial process

As a means of ensuring quality and transparency in the editorial process, DOAJ requires that every journal indexed in it carries out some form of peer review, and the publisher is requested to provide details on exactly which form of peer review is applied. We also ask for details on a policy for plagiarism control (but this is not a required item), and we require full credentials and affiliations of the editorial board members. We will look for sufficient proof that all members are actively involved in editorial tasks and are not simply names on a list. We will randomly check editorial board members by approaching them personally by mail and/or phone.

With respect to openness, we require that the journal have an open access statement on the website, which is in full compliance with the BOAI statement. We try to encourage publishers to state more than ‘This is an open access journal’ because there is far greater depth to the definition of ‘open access’ than just free to read. Open Access is not only about ‘free to read’ but about re-use, i.e. being allowed to use a work without any restrictions at all or often with some publisher-determined restrictions. Furthermore we do not accept journals that publish open content after an embargo period. All content must be available immediately upon publication.

Content licensing and copyright issues

We encourage that copyright and licensing information is provided with all individual articles. This is because articles have a post-publication afterlife that is often separate from the journal. To allow users of the article to know easily what they are allowed to do with the content is an important service that publishers should provide to readers. Embedding the licensing information into the articles is not a requirement for acceptance into DOAJ, but it is required for the Seal.

The application of a Creative Commons licence is encouraged but is not actually required for acceptance. Publishers may choose to use a non-CC equivalent so that licensing terms in some form are always available on the site. Creative Commons licences have been part of the DOAJ fabric since 2008, but it is important that DOAJ makes concessions for non-Creative Commons licences because, at the time of creating the new criteria, CC licences were not officially recognised in every country in the world, and DOAJ must remain as inclusive as possible. A journal using a non-CC licence, but stating clearly on the site what the terms of the licence are must indicate that in their application. DOAJ sees CC licences as Best Practice so journals using a CC BY, CC BY-SA or CC BY-NC will qualify for the Seal. Other publisher-made specific licensing terms will be judged on an individual basis. If ‘No’ is selected in the licensing question (i.e. no licensing conditions exist that explicitly allow reuse and remixing of the content), the journal will not be accepted into DOAJ. If ‘Other’ is selected, the licence or publishing agreement must allow reuse and remixing of the content.

Another area where we recommend a best practice is to encourage a lenient policy about depositing copies of content into institutional repositories. Policies to do this vary from publisher to publisher, and often from journal to journal, making it confusing for an author to know exactly what he/she can do with his/her own article. Databases of journals’ policies, such as Sherpa/Romeo [14], exist to combat this confusion so that all policies can be accessed permanently and in a central location. Stating a lenient policy on its website shows that a journal is committed to a deeper form of open access and recognises the author's right to archive a copy of his/her own work. This is why DOAJ considers that the use of directories like Sherpa/Romeo constitute Best Practice. Romeo uses DOAJ's metadata, so some of the entries in Romeo are shells, or placeholders, awaiting an official update from the publisher. Anyone who wants to improve a journal's entry in DOAJ can do so by contacting Sherpa and suggesting an update [14].

We are convinced that authors should retain unrestricted copyright and have made this a fundamental requirement for the Seal. With unrestricted copyright we mean that the author retains all rights, with no exception. There are instances where publishers say that the author retains copyright but, at the same time, require exclusive publishing rights and/or a transfer of commercial rights. In these instances, the author clearly does not retain unrestricted copyright. Because of the complexity of the copyright issue, we published an extensive explanation including examples and references to the literature in the form of two blog posts on the DOAJ website [15, 16].

We do accept journals where copyright has to be transferred to the publisher, as long as articles are published open access in compliance with the BOAI definition. However, we think that this situation is disadvantageous for the authors since the publisher will be in full control of the work. For instance, when an author has transferred copyright to a publisher, and the publisher applies CC BY-NC licensing, the publisher will have the commercial rights to the work. However in the case of an author retaining the copyright and the work is published using a CC BY-NC licence, the author retains all rights including commercial rights to his/her work (in accordance with the recommendations from Science Europe) [3].

THE DOAJ SEAL

Journals that fulfil the minimum requirements are accepted into DOAJ and automatically get a green Tick next to them to show that they have passed the newer, tighter criteria. In order to promote best open access publishing practice, fulfilling seven extra criteria make open access journals eligible for the DOAJ Seal.

Note that all journals in DOAJ must achieve a certain level of quality and best practice to be indexed and inclusion in the DOAJ already denotes quality and the seriousness of the journal. The Seal is intended as a badge reserved for those journals and publishers who really adhere to best practice in the context of open access publishing. Note also that the Seal is proof of outstanding quality in (open access) publishing practice and is not an assessment of the quality of the science.

To qualify for the Seal the journal must:

have an archival arrangement in place with an external party for the long-term preservation and archiving of the journal's published content.

provide permanent identifiers in the papers published. By permanent identifiers we mean a unique identifier that is assigned to the article upon publication and remains with the article forever. The most common of these is the DOI which is used in a scheme governed by CrossRef.

provide article level metadata to DOAJ. A grace period of 3 months exists to allow publishers to get their content into the right format for ingestion into DOAJ.

embed machine-readable CC licensing information in article-level metadata, as we mentioned above. It is important that, wherever someone is reading the content, they know exactly what they are allowed to do with the content, especially around re-use and sharing.

allow reuse and remixing of content in accordance with a Creative Commons licence or other type of licence with similar conditions.

have a deposit policy registered in a deposit policy directory. It is often the case that a journal indexed in DOAJ will have a skeleton entry in the Sherpa/Romeo database because the latter has ingested our metadata. This skeleton entry is not enough, and publishers are encouraged to contact Sherpa/Romeo directly and update their entry [14].

allow the author to hold the copyright without restrictions. This is the newest Seal criteria.

The Seal criteria are mentioned at the bottom of every application form and are meant to provide an incentive for publishers to have their journals stand out in DOAJ by displaying the DOAJ Seal in their journal record for outstanding open access publishing standards. Several of the Seal criteria were already discussed in the preceding sections but items 5 and 7 in the list above need more detailed explanation.

Criterion 5 (allow reuse and remixing of the content) is meant to assess a key quality of open access, namely the right for users to reuse the content of a publication in as many ways possible. For the Seal we do allow two publishing restrictions: that the work can be used only non-commercially, and that the work may be shared only using a similar licence as the original licence. For inclusion in DOAJ we furthermore accept licensing conditions that specify the condition that (commercial or non-commercial) derivatives of the work are not allowed. However, we do want to state clearly our preference for the use of a CC BY or similar licence which permits unrestricted reuse of the content of a scientific publication.

Criterion 7 for the Seal concerns the requirement that the author retains unrestricted copyright AND unrestricted publishing rights. Many publishers seem to have a wrong understanding of the concept of unrestricted copyright or unrestricted publishing rights. For instance, when a publishing agreement states that the author retains copyright but grants the publisher EXCLUSIVE publishing right, DOAJ considers this a case of RESTRICTED copyright and RESTRICTED publishing rights for the author. Therefore, these cases will not be eligible for the DOAJ SEAL. Also in cases where publishers demand the commercial rights and leave the (restricted) copyright with the author the Seal will not be awarded.

The requirement for retaining unrestricted copyright was recently also adopted by Science Europe as a requirement for being eligible for European research funding [3].

INTRODUCING THE DOAJ API

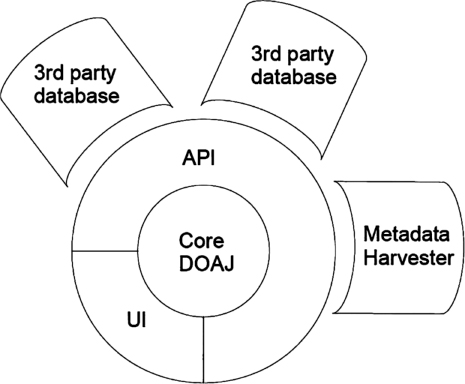

One of the greatest advantages of DOAJ, for journals and authors alike is that being indexed in DOAJ vastly increases the visibility and discoverability of the published content. A survey of publishers in 2013 [17] confirmed that, for them, this was the single greatest reason to be included in DOAJ. DOAJ has excellent page ranking in Google and a journal's home page in DOAJ floats to the top of searches in a way that the actual web sites’ URLs do not on their own. Providing article metadata to DOAJ is a service to authors, and this is one of the reasons that we include this criterion in the DOAJ Seal. Furthermore, DOAJ's metadata are made available in many different ways and is used all over the web. Almost everything that we do at DOAJ in terms of development aims at increasing the visibility of peer-reviewed, open access content, and the API and metadata harvester pilot projects are no different. As the year draws to an end, we will have launched an API with a suite of functionalities and will be mid-way through a pilot for harvesting metadata.

Our API [18] is being launched in three phases. Phase 1, already launched, is a Discovery API and opens up the database to external queries and localised searching. It allows developers to incorporate the DOAJ into their own database, increasing the visibility of all DOAJ content in numerous places. Although, we have already enhanced that visibility through discoverability and linking tools, such as OpenURL and OAI-PMH, the API allows so much more, not least in terms of creating customised searches and datasets. Phase 2 will see the launch of a part of the API that will allow publishers to create, read, update and delete (CRUD) their journal and article metadata in DOAJ. This will be huge for the open access publishers community. Unlike other indexers, DOAJ does not go out and collect metadata from indexed journals but relies on the publisher themselves to upload content to us. Of course, this is a limitation and the amount of metadata uploaded is only a portion of what it could be. By enabling the CRUD API, publishers will, almost seamlessly, be able to upload their article content to us with a minimum amount of effort. Phase 3 will enable bulk applications, which will be music to the ears of some of our larger customers, and some widgets, allowing DOAJ a greater, branded visibility in external databases.

The metadata harvester pilot will allow DOAJ to go out and, for the first time ever, collect article metadata for the journals indexed in DOAJ. This will almost double the amount of articles in the database and will put DOAJ way in front of other indexers. The pilot will focus on retrieving article metadata for all the DOAJ-indexed journals in Europe PMC, including all of PLoS and Biomed Central. We estimate that this could add up to 2 million articles, although a closer approximation will not be available until the project has been scoped in November. One of the best advantages of the harvester pilot is that it will do away with the limitation that we have currently on our XML ingestion: DOAJ can only accept a DOAJ-specific flavour of XML and producing that XML can come with a cost for publishers who do not already do this or who are not on the OJS platform. (The OJS-hosting software comes with a handy plugin that generates DOAJ XML.)

DOAJ METADATA AND ITS USE BY OTHER SERVICES

It has often been stated that DOAJ is at the centre of the open access movement, and it's actually pretty accurate. Do a search in Google for any journal in DOAJ, and almost the same database URLs are returned time and again. Digging into those databases shows often shows that a journal's entry is credited to DOAJ.

With all the new metadata that the new criteria request of publishers, our metadata are richer and more accurate than ever before.

Our metadata are opened up for use in various flavours: OAI-PMH, CSV, OpenURL, Atom, JSON and soon via the API. It is ingested into other products and services, both open source and proprietary. We have evidence of other services directly reproducing our metadata and using them to fill out their own products. We know that subscriptions services by aggregators like EBSCO and Serial Solutions incorporate our metadata into their products. That so many services rely on the quality of our data is made apparent by the frequent emails that we get asking for corrections or clarifications on a journal entry or a specific article. We know that libraries like to use our data since these give visibility to the open access journals that students and faculty can use.

DOAJ has become one of the most important sources for open access information. Over the last 3 years, it has evolved into a unique source containing manually vetted high-quality, open access journals. Other sources for obtaining information on open access journals are Thomson Reuters [19] (uses data from DOAJ), the recently launched Scopus open access database (open access is flagged based on information taken from DOAJ and ROAD [20]), and ROAD (where DOAJ is the single most important data source).

DOAJ enjoys the relatively unique position of being able to serve all the major stakeholders in scholarly communication.

Since DOAJ provides the authoritative list of good open access journals and article-level metadata for harvesting, library catalogues and library systems all over the world have chosen DOAJ as their preferred source for bibliographic data for their library services. Furthermore, all the major discovery service providers (EBSCO, Proquest, Exlibris) are harvesting data from DOAJ. This means DOAJ metadata are integrated into their services and distributed to thousands of university libraries (and public libraries). Journals indexed in DOAJ are presented to the library users seamlessly and next to the subscription journals.

Universities and university libraries operate open access publication funds to support payments of APCs. More often than not eligibility of journals for this kind of support is based on whether or not the journal is listed in DOAJ. Research funders and institutions with open access mandates use the information DOAJ provides about indexed journals to determine whether journals comply with their mandates, for instance in terms of licensing, archiving and deposit policies.

DOAJ is also the primary resource for researchers and scholars studying scholarly communication and open access publishing. DOAJ data are frequently used as the data source in papers and articles and DOAJ is often cited in references.

FUNDING

As all of the services that DOAJ provides are without any charge whatsoever, the development and operation of DOAJ is completely dependent on support from the community. Annual membership fees from hundreds of academic libraries and library consortia from more than 25 countries account for 50% of the financial support. Many small publishers support DOAJ with minor contributions and all the major publishers and aggregators support DOAJ by means of yearly sponsorships. Sponsorships account for 50% of the income.

During the recent years the support from the community has increased yearly by 25%. Information about the DOAJ financials can be seen here [21].