- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Hypertensive Disorders in Pregnancy and Mortality at Delivery Hospitalization — United States, 2017–2019

research-article

Nicole D. Ford , PhD

1

,

,

Shanna Cox , MSPH

1 ,

Jean Y. Ko , PhD

1 ,

Lijing Ouyang , PhD

1 ,

Lisa Romero , DrPh

1 ,

Tiffany Colarusso , MD

1 ,

Cynthia D. Ferre , MA

1 ,

Charlan D. Kroelinger , PhD

1 ,

Donald K. Hayes , MD

2 ,

Wanda D. Barfield , MD

1

29 April 2022

Read this article at

There is no author summary for this article yet. Authors can add summaries to their articles on ScienceOpen to make them more accessible to a non-specialist audience.

Abstract

Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy (HDPs), defined as prepregnancy (chronic) or pregnancy-associated

hypertension, are common pregnancy complications in the United States.* HDPs are strongly

associated with severe maternal complications, such as heart attack and stroke (

1

), and are a leading cause of pregnancy-related death in the United States.

†

CDC analyzed nationally representative data from the National Inpatient Sample to

calculate the annual prevalence of HDP among delivery hospitalizations and by maternal

characteristics, and the percentage of in-hospital deaths with an HDP diagnosis code

documented. During 2017–2019, the prevalence of HDP among delivery hospitalizations

increased from 13.3% to 15.9%. The prevalence of pregnancy-associated hypertension

increased from 10.8% in 2017 to 13.0% in 2019, while the prevalence of chronic hypertension

increased from 2.0% to 2.3%. Prevalence of HDP was highest among delivery hospitalizations

of non-Hispanic Black or African American (Black) women, non-Hispanic American Indian

and Alaska Native (AI/AN) women, and women aged ≥35 years, residing in zip codes in

the lowest median household income quartile, or delivering in hospitals in the South

or the Midwest Census regions. Among deaths that occurred during delivery hospitalization,

31.6% had any HDP documented. Clinical guidance for reducing complications from HDP

focuses on prompt identification and preventing progression to severe maternal complications

through timely treatment (

1

). Recommendations for identifying and monitoring pregnant persons with hypertension

include measuring blood pressure throughout pregnancy,

§

including self-monitoring. Severe complications and mortality from HDP are preventable

with equitable implementation of strategies to identify and monitor persons with HDP

(

1

) and quality improvement initiatives to improve prompt treatment and increase awareness

of urgent maternal warning signs (

2

).

Delivery hospitalization data for 2017–2019 were analyzed from the National Inpatient

Sample, a nationally representative sample of all U.S. hospital discharges.

¶

CDC identified delivery hospitalizations among females aged 12–55 years using International

Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) diagnosis

and procedure codes pertaining to delivery and diagnosis-related group delivery codes.**

HDPs were categorized using ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes

††

for chronic hypertension,

§§

pregnancy-associated hypertension,

¶¶

and unspecified maternal hypertension. Deaths were identified based on patient hospital

discharge disposition.

Weighted annual prevalence (percentage) and 95% CI for HDP overall and by each type

were calculated. Change in annual prevalence of HDP overall and by type was assessed

using a linear trend test. Pooling data from this period, CDC calculated the weighted

prevalence and 95% CIs for HDP by selected maternal characteristics (i.e., age group,

race and ethnicity, and primary payer at delivery hospitalization) and characteristics

of the community in which they lived (i.e., county-level rural-urban classification,

zip code–level median household income, and hospital region).*** Rao-Scott chi-square

tests of independence were used to assess whether HDP prevalence differed by characteristics.

Percentage of deaths during delivery hospitalization with a documented HDP diagnosis

code were calculated. All analyses were conducted using SAS software (version 9.4;

SAS Institute); SAS survey procedures and weighting were used to account for complex

sampling in the National Inpatient Sample. This activity was reviewed by CDC and was

conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy.

†††

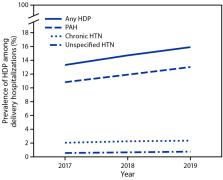

During 2017–2019, the prevalence of HDP among delivery hospitalizations increased

from 13.3% to 15.9% (Figure 1), an increase of approximately 1 percentage point annually.

Linear trend tests suggested that change in annual prevalence of HDP overall, pregnancy-associated

hypertension, and chronic hypertension increased during 2017–2019, while prevalence

of unspecified maternal hypertension remained stable. The prevalence of pregnancy-associated

hypertension increased from 10.8% to 13.0% and that of chronic hypertension increased

from 2.0% to 2.3%.

FIGURE 1

Prevalence of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy* among delivery hospitalizations,

by year — National Inpatient Sample, United States, 2017–2019

Abbreviations: HDP = hypertensive disorder in pregnancy; HTN = hypertension; PAH =

pregnancy-associated hypertension.

* HDPs are defined as chronic hypertension, pregnancy-associated hypertension (i.e.,

gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, eclampsia, and chronic hypertension with superimposed

preeclampsia), and unspecified maternal hypertension.

This figure is a line chart showing the prevalence of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy

among delivery hospitalizations, by year, in the United States during 2017–2019 according

to the National Inpatient Sample.

During 2017–2019 combined, prevalence of HDP overall was 14.6%. Prevalence varied

overall and by HDP type for all maternal characteristics evaluated in the study (Table).

Prevalence of any HDP was higher among delivery hospitalizations to women aged 35–44

(18.0%) and 45–55 years (31.0%) than to younger women, to Black (20.9%) and AI/AN

(16.4%) women than to women of other racial and ethnic groups, to those residing in

rural counties (15.5%) and in zip codes in the lowest median household-level income

quartile (16.4%) than those residing in metropolitan or micropolitan counties or in

zip codes in higher household-level income quartiles, or delivering in hospitals in

the South (15.9%) or Midwest (15.0%) U.S. Census regions than in other Census regions.

These differences in HDP prevalence were similar across HDP types.

TABLE

Prevalence of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy, by patient-, hospital- and zip

code–level characteristics — National Inpatient Sample, United States, 2017–2019

Characteristic

Any hypertensive disorder in pregnancy*

Chronic hypertension

Pregnancy-associated hypertension

Unspecified maternal hypertension

No.†

Row % (95% CI)

No.

Row % (95% CI)

No.

Row % (95% CI)

No.

Row % (95% CI)

Total no. of cases

319,913

—

47,218

—

259,458

—

13,237

—

Maternal age group, yrs

12–24

73,421

13.9 (13.7–14.1)

5,593

1.1 (1.0–1.1)

65,378

12.4 (12.2–12.5)

2,450

0.5 (0.4–0.5)

25–29

85,358

13.5 (13.3–13.7)

10,984

1.7 (1.7–1.8)

71,010

11.2 (11.1–11.4)

3,364

0.5 (0.5–0.6)

30–34

89,242

14.3 (14.1–14.4)

14,982

2.4 (2.3–2.4)

70,287

11.2 (11.1–11.4)

3,973

0.6 (0.6–0.7)

35–44

70,395

18.0 (17.7–18.2)

15,341

3.9 (3.8–4.0)

51,672

13.2 (13.0–13.4)

3,382

0.9 (0.8–0.9)

45–55

1,497

31.0 (29.7–32.4)

318

6.6 (5.9–7.3)

1,111

23.0 (21.8–24.2)

68

1.4 (1.1–1.7)

Race and ethnicity

§

Asian or Pacific Islander

12,183

9.3 (8.8–9.7)

1,616

1.2 (1.1–1.3)

10,134

7.7 (7.3–8.1)

433

0.3 (0.3–0.4)

Black

66,316

20.9 (20.5–21.2)

13,639

4.3 (4.2–4.4)

49,568

15.6 (15.3–15.9)

3,109

1.0 (0.9–1.0)

Hispanic

54,702

12.5 (12.2–12.8)

6,561

1.5 (1.5–1.5)

46,148

10.6 (10.3–10.8)

1,993

0.5 (0.4–0.5)

American Indian and Alaska Native

2,525

16.4 (15.4–17.5)

318

2.1 (1.8–2.3)

2,103

13.7 (12.7–14.6)

104

0.7 (0.5–0.8)

Another race

11,659

12.0 (11.6–12.3)

1,400

1.4 (1.4–1.5)

9,781

10.1 (9.7–10.4)

478

0.5 (0.4–0.5)

White

162,122

14.7 (14.5–14.9)

22,358

2.0 (2.0–2.1)

133,052

12.1 (11.9–12.2)

6,712

0.6 (0.6–0.6)

Missing

10,406

12.7 (12.2–13.1)

1,326

1.6 (1.5–1.7)

8,672

10.6 (10.2–11.0)

408

0.5 (0.4–0.6)

Payer

Public¶

139,227

14.8 (14.6–15.0)

21,541

2.3 (2.2–2.3)

111,543

11.8 (11.7–12.0)

6,143

0.7 (0.6–0.7)

Private insurance

166,455

14.8 (14.7–15.0)

23,826

2.1 (2.1–2.2)

136,153

12.1 (12.0–12.3)

6,476

0.6 (0.6–0.6)

Self-pay/Other

13,837

11.9 (11.6–12.2)

1,791

1.5 (1.5–1.6)

11,443

9.8 (9.5–10.1)

603

0.5 (0.5–0.6)

Rurality (county-level)

Metropolitan

275,342

14.6 (14.4–14.8)

40,136

2.1 (2.1–2.2)

224,232

11.9 (11.7–12.0)

10,974

0.6 (0.6–0.6)

Micropolitan

25,844

14.8 (14.5–15.0)

4,026

2.3 (2.2–2.4)

20,497

11.7 (11.5–11.9)

1,321

0.8 (0.7–0.8)

Rural**

18,139

15.5 (15.1–15.8)

2,980

2.5 (2.4–2.7)

14,241

12.1 (11.9–12.4)

918

0.8 (0.7–0.8)

Median household-level income national quartile for patient zip code

††

Q1

98,661

16.4 (16.1–16.6)

16,218

2.7 (2.6–2.8)

78,022

12.9 (12.7–13.2)

4,421

0.7 (0.7–0.8)

Q2

81,089

14.7 (14.5–14.9)

11,916

2.2 (2.1–2.2)

65,747

11.9 (11.8–12.1)

3,426

0.6 (0.6–0.6)

Q3

77,387

14.4 (14.3–14.6)

10,829

2.0 (2.0–2.1)

63,629

11.9 (11.7–12.0)

2,929

0.5 (0.5–0.6)

Q4

60,014

12.7 (12.5–12.9)

7,830

1.7 (1.6–1.7)

49,857

10.5 (10.3–10.7)

2,327

0.5 (0.5–0.5)

Hospital region

§§

Northeast

48,527

13.9 (13.5–14.4)

6,746

1.9 (1.8–2.0)

40,017

11.5 (11.1–11.9)

1,764

0.5 (0.5–0.5)

Midwest

69,181

15.0 (14.7–15.3)

9,736

2.1 (2.0–2.2)

56,611

12.3 (12.0–12.5)

2,834

0.6 (0.6–0.6)

South

136,435

15.9 (15.7–16.2)

22,355

2.6 (2.5–2.7)

107,940

12.6 (12.4–12.8)

6,140

0.7 (0.7–0.7)

West

65,770

12.7 (12.4–13.0)

8,381

1.6 (1.6–1.7)

54,890

10.6 (10.4–10.9)

2,499

0.5 (0.5–0.5)

Abbreviation: Q = quartile.

* Any hypertensive disorder in pregnancy includes chronic hypertension, pregnancy-associated

hypertension, and unspecified maternal hypertension.

† Numbers are unweighted.

§ Patients with Hispanic ethnicity are classified as Hispanic and all non-Hispanic

patients are classified according to their reported race. The Healthcare Cost and

Utilization Project (HCUP) race and ethnicity category Native American is expressed

as American Indian and Alaska Native.

¶ Public insurance includes Medicare and Medicaid.

** Rural defined as nonmetropolitan and nonmicropolitan counties.

†† 2017 (Q1 = $1–$43,999, Q2 = $44,000–$55,999, Q3 = $56,000–73,999, Q4 = ≥$74,000);

2018 (Q1 = $1–$45,999, Q2 = $46,000–$58,999, Q3 = $59,000–$78,999, Q4 = ≥$79,000);

2019: Q1 = $1–$47,999, Q2 = $48,000–$60,999, Q3 = $61,000–$81,999, Q4 = ≥$82,000.

§§ Hospital region is the census region as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau.

Among maternal deaths that occurred during delivery hospitalization, 31.6% had any

HDP documented and 24.3% had pregnancy-associated hypertension documented. Chronic

or unspecified maternal hypertension was documented in 7.4% of deaths

§§§

(Figure 2).

FIGURE 2

Proportion of deaths* occurring during delivery hospitalization with a documented

diagnosis code of a hypertensive disorder in pregnancy

†

— National Inpatient Sample, United States, 2017–2019

Abbreviation: HDP = hypertensive disorder in pregnancy.

* This study did not assign cause of death but instead examined the proportion of

in-hospital deaths with an HDP diagnosis code documented among delivery hospitalizations.

†

HDPs are defined as chronic hypertension, pregnancy-associated hypertension (i.e.,

gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, eclampsia, and chronic hypertension with superimposed

preeclampsia), and unspecified maternal hypertension. Proportions for chronic and

unspecified maternal hypertension are combined to conform to the Agency for Healthcare

Research and Quality’s data use agreement, which prohibits reporting estimates based

on fewer than 11 unweighted observations.

This figure is a bar chart showing the proportion of deaths occurring during delivery

hospitalization with a documented diagnosis code of a hypertensive disorder in pregnancy

in the United States during 2017–2019— according to the National Inpatient Sample.

Discussion

During 2017–2019, HDPs affected approximately one in seven delivery hospitalizations;

prevalence increases were largely driven by increases in pregnancy-associated hypertension.

HDPs were documented in approximately one in five delivery hospitalizations among

Black women and one in three among women aged 45–55 years. An HDP diagnosis code was

documented in approximately one in three deaths occurring during delivery hospitalization.

Timely diagnosis and treatment of HDP are critical to preventing severe complications

and mortality (

1

).

Prevalence of risk factors for HDP, such as advanced maternal age, obesity, and diabetes

mellitus, have increased in the United States (

1

), and might explain the increase in HDP prevalence. Women with a history of pregnancy-associated

hypertension are at increased risk for cardiovascular disease compared with women

with normotensive pregnancies.

¶¶¶

Addressing risk factors for HDP across the lifespan is important for preventing HDP

and improving future health.****

There are substantial racial and ethnic disparities in HDP prevalence. Compared with

non-Hispanic White women, non-Hispanic Black women have higher odds of entering pregnancy

with chronic hypertension and developing severe preeclampsia (

3

). Factors that contribute to racial and ethnic inequities in chronic and pregnancy-induced

hypertension include higher prevalences of HDP risk factors (

4

), as well as differences in access to health care and the quality of health care

delivered (

5

). Racial bias within the U.S. health care system can affect HDP care from screening

and diagnosis to treatment (

6

). Furthermore, psychosocial stress from experiencing racism is associated with chronic

hypertension (

7

). In a study of racial and ethnic disparities in pregnancy-related deaths, those

caused by HDP among Black and AI/AN women were found to be substantially higher than

those among White women (

8

), highlighting the importance of addressing HDP to reduce inequities in pregnancy-related

mortality.

Regional and rural-urban differences in HDP prevalence have been previously reported

(

9

). Place-based disparities in HDP prevalence might be due to differences in prevalence

of HDP risk factors, including diet, tobacco use, physical activity patterns, poverty,

or access to care.

††††

Rural counties are at higher risk for pregnancy-related mortality than metropolitan

counties (

10

). A strategy to address place-based disparities in HDP and pregnancy-related mortality

can include strengthening regional networks of health care facilities providing risk-appropriate

maternal care through telemedicine and transferring delivery care of persons with

high-risk conditions to facilities that can provide specialty services.

§§§§

Clinical guidance for reducing complications from HDP focuses on prompt identification

and preventing progression to severe maternal complications. Recommendations for identifying

and monitoring pregnant persons with hypertension include measuring blood pressure

throughout pregnancy, including self-monitoring.

¶¶¶¶

Recommendations for preventing preeclampsia include low-dose aspirin for persons at

risk and exercise programs.***** Once a diagnosis of an HDP is received, management

strategies include blood pressure–lowering medication,

†††††

prevention of eclamptic seizures (e.g., administration of magnesium sulfate), and

close maternal and fetal monitoring and coordination and continuity of care during

the postpartum period.

§§§§§

At the systems level, perinatal quality collaboratives (PQCs)

¶¶¶¶¶

implement evidence-based quality improvement initiatives in health care facilities,

including those to address severe hypertension.****** PQCs use collaborative learning,

training, toolkits, and maternal safety bundles (e.g., Alliance for Innovation on

Maternal Health Patient Safety Bundles

††††††

) to improve the quality of care and outcomes statewide. Maternal mortality review

committees (MMRCs) provide recommendations for preventing future pregnancy-related

deaths, including those attributable to HDP, and often collaborate with PQCs to translate

MMRC recommendations into clinical and health systems interventions. Health communication

campaigns increase awareness of urgent warning signs of HDP that indicate need for

immediate care.§§§§§§ Strategies to address health inequities in HDP include addressing

implicit, institutional, and structural racism, disparate access to clinical care,

social determinants of health, and engagement of community partners (

2

).

The findings in this report are subject to at least four limitations. First, identification

of delivery hospitalizations and HDP is dependent upon accurate ICD-10-CM coding.

Less severe cases of HDP might not be coded. In this study, approximately 4% of HDP

was documented as unspecified maternal hypertension, which precludes accurate documentation

of HDP type. Second, deaths identified using discharge disposition might underestimate

deaths during delivery hospitalization.¶¶¶¶¶¶ These data do not represent the universe

of pregnancy-related deaths, such as those that occur preceding or after delivery

hospitalizations.******* This study did not assign cause of death but instead examined

the proportion of in-hospital deaths occurring during delivery hospitalization with

an HDP diagnosis code documented. Third, CDC was unable to identify persons who delivered

more than once during the study period; the unit of analysis is delivery hospitalization.

Finally, small sample sizes did not permit the disaggregation of deaths attributable

to less frequent types of HDP and other maternal characteristics.

The prevalence of HDP increased during the 3-year study period with noted racial and

ethnic, sociodemographic, and place-based disparities. Severe HDP-associated maternal

complications and mortality are preventable with equitable implementation of public

health and clinical strategies. These include efforts across the life course for preventing

HDP, identifying, monitoring, and appropriately treating those with HDP with continuous

and coordinated care, increasing awareness of urgent maternal warning signs, and implementing

quality improvement initiatives to address severe hypertension.

Summary

What is already known about this topic?

Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy (HDPs) are common pregnancy complications and

leading causes of pregnancy-related death in the United States.

What is added by this report?

During 2017–2019, HDP prevalence among delivery hospitalizations increased from 13.3%

to 15.9%. The highest prevalence was among women aged 35–44 (18.0%) and 45–55 years

(31.0%), and those who were Black women (20.9%) or American Indian and Alaska Native

women (16.4%). Among deaths occurring during delivery hospitalization, 31.6% had a

diagnosis code for HDP documented.

What are the implications for public health practice?

Severe HDP–associated complications and mortality are preventable with equitable implementation

of quality improvement initiatives to recognize and promptly treat HDP and to increase

awareness of urgent maternal warning signs.

Related collections

Most cited references9

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Pregnancy-Related Deaths — United States, 2007–2016

Emily Petersen, Nicole Davis, David Goodman … (2019)

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Reducing Disparities in Severe Maternal Morbidity and Mortality

ELIZABETH A. HOWELL (2018)

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Hypertension in Pregnancy: Diagnosis, Blood Pressure Goals, and Pharmacotherapy: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association

Vesna D. Garovic, Ralf Dechend, Thomas Easterling … (2021)