- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

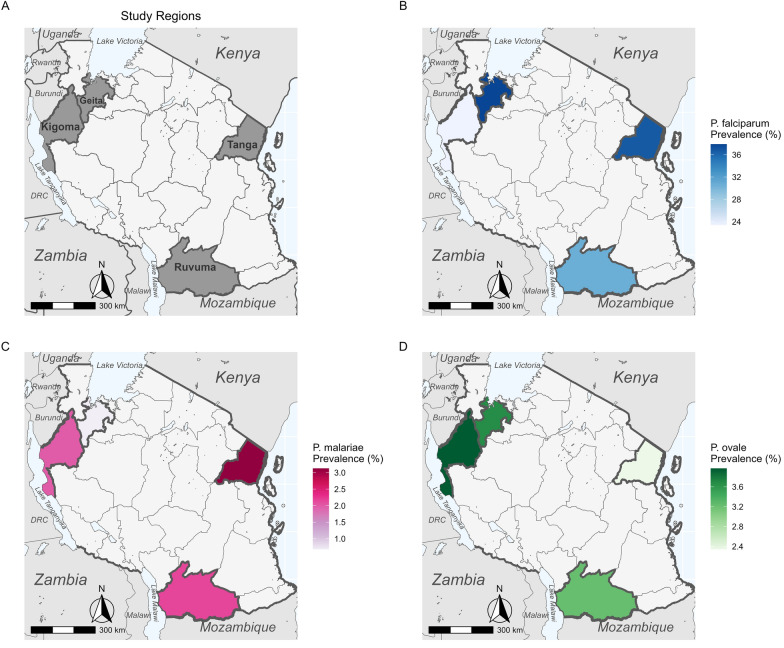

Prevalence of non- falciparum malaria infections among asymptomatic individuals in four regions of Mainland Tanzania

Read this article at

Abstract

Background

Recent studies point to the need to incorporate the detection of non-falciparum species into malaria surveillance activities in sub-Saharan Africa, where 95% of the world’s malaria cases occur. Although malaria caused by infection with Plasmodium falciparum is typically more severe than malaria caused by the non-falciparum Plasmodium species P. malariae, P. ovale spp. and P. vivax, the latter may be more challenging to diagnose, treat, control and ultimately eliminate. The prevalence of non-falciparum species throughout sub-Saharan Africa is poorly defined. Tanzania has geographical heterogeneity in transmission levels but an overall high malaria burden.

Methods

To estimate the prevalence of malaria species in Mainland Tanzania, we randomly selected 1428 samples from 6005 asymptomatic isolates collected in previous cross-sectional community surveys across four regions and analyzed these by quantitative PCR to detect and identify the Plasmodium species.

Results

Plasmodium falciparum was the most prevalent species in all samples, with P. malariae and P. ovale spp. detected at a lower prevalence (< 5%) in all four regions; P. vivax was not detected in any sample.

Related collections

Most cited references17

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

School-Age Children Are a Reservoir of Malaria Infection in Malawi

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Plasmodium ovale: parasite and disease.

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found