INTRODUCTION

Sympathetic ophthalmia (SO) is a bilateral diffuse granulomatous intraocular inflammation that occurs in most cases within days or months after either surgery or penetrating trauma to one eye. The injured eye is known as the exciting eye and the fellow eye, developing inflammation days to years later, as the sympathizing eye. The sympathizing eye demonstrates sings of the ocular inflammation without any apparent reason. Although rare, SO remains an important public health problem because it can cause bilateral blindness. The time from ocular injury to onset of SO varies greatly, ranging from a few days to decades, with 80% of the cases occurring within 3 months after injury to the exciting eye and 90% within 1 year.12

This ocular disease is probably the best known and the most classic model of an autoimmune- associated disease occurring in humans. The reason for naming this disease sympathetic ophthalmia remains obscure. One possible explanation is that the sympathetic pathways (optic nerve and optic chiasm) may be the pathway from the inciting eye to the sympathizing eye.3 However, current evidence suggests a role for immune dysregulation as a primary etiological mechanism. There appears to be a cell-mediated immune response directed against ocular self-antigens found on photoreceptors, the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and/or choroidal melanocytes.

The condition was first recognized by Hippocrates, but was first described and named by Mackenzie in the mid-1800s.34 Fuch's provided the first histopathologic details in 1905.5 He established it as a separate disease entity, distinct from other ocular inflammatory disorders. Fuchs and Dalen independently described the inflammatory nodular aggregates termed “Dalen-Fuchs nodules.”6

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Given its rare occurrence, the true incidence of SO is difficult to establish and literature reports are variable, likely owing to the fact that the diagnosis of SO is based on clinical findings rather than on serological testing or histopathology. The true incidence is unknown because of lack of pathologic proof, the difficulty in studying sufficiently large cases series and the fact that most data are from the dated literature that often confused SO with other forms of uveitis.7 In 1982, Gass reported the prevalence of SO at 0.01% following pars plana vitrectomy, and a 0.06% after other penetrating ocular trauma.8 Epidemiological estimates have shown the incidence to be 0.2% to 0.5% after penetrating ocular injuries and 0.01% after intraocular surgery.910 According to Gomi et al,11 SO accounted for approximately 0.3% of the uveitis and the one-year incidence was calculated to be a minimum of 0.03/100,000 population.12

There is no racial or age predisposition. The incidence of SO is equal in males and females after surgery; the disease occurs more frequently in males after trauma. This likely reflects the difference in the frequency of ocular injury between genders. SO occurs more often after non-surgical trauma.1314 However, SO has been reported after various intraocular procedures such as, trans-scleral neodymium: YAG cyclodestruction, cataract extraction, evisceration, paracentesis, iridectomy, pars plana vitrectomy, and retinal detachment repair.15–18 SO has also been reported after perforated corneal ulcer, radiation for choroidal melanoma and external beam radiation.19–21 Vitreoretinal surgery and cyclodestructive procedures are considered risk factors for SO.1517–18 Recently, SO has been described after 23-gauge vitrectomy.18 Although some recent reviews consider ocular surgery, particularly vitreoretinal surgery, as the main risk for SO, our experience is that SO is still more frequent after non-surgical trauma (unpublished data).

SO has been associated with particular major histocompatibility antigen (MHC) haplotypes. This finding suggests a role for immune dysregulation, increased susceptibility, and increased severity associated with pathogenesis. Patients with SO are more likely to express human leukocyte antigen DR4 (HLA-DR4, and closely related HLADQw3 and HLA-DRw53) phenotype.22 These phenotypes are also found more frequently in patients with Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) disease. HLA-DRB1*04 and HLA-DQA1*03 haplotypes have been considered markers of increased SO susceptibility and severity in British and Irish patients.23 Therefore, select patients may have a genetic predisposition to developing SO following accidental or surgical ocular trauma.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Onset occurs within 1 month in approximately 17% of cases; within 3 months in 50%; within 6 months in 65%, and within the first year after injury in 90%. After the inciting event, traumatic or surgical, bilateral intraocular inflammation has been reported between 1 week and 66 years.24

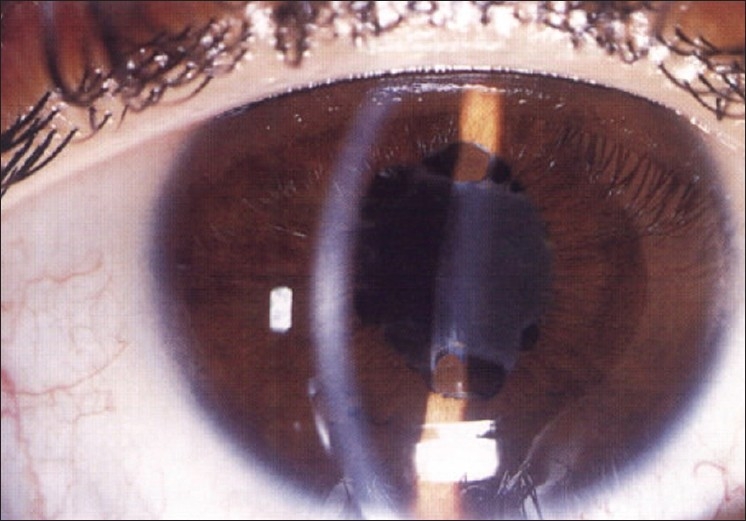

Sympathetic ophthalmia presents as a bilateral diffuse uveitis. Patients report insidious onset of blurry vision, pain, epiphora, and photophobia in the sympathizing, non-injured eye. Classically this is accompanied by conjunctival injection and a granulomatous anterior chamber reaction with mutton-fat KPs on the corneal endothelium; however, the anterior chamber reaction can be relatively mild, and the inflammation can be non-granulomatous. The inflammation can be so mild that the term “sympathetic irritation” is used. The iris may thicken from lymphocytic infiltration; the severe inflammation may lead to formation of posterior synechiae [Figure 1]. Intraocular pressure may be elevated secondary to inflammatory cell blockage of the trabecular meshwork, or it may lower as a result of ciliary body shutdown.

Acute anterior uveitis with keratic precipitates, posterior synechiae and fibrin on the anterior lens capsule in the right eye of a 25-year-old male, who had sustained a penetrating trauma to his left eye 3 months earlier (Reprinted with permission from BenErza D25)

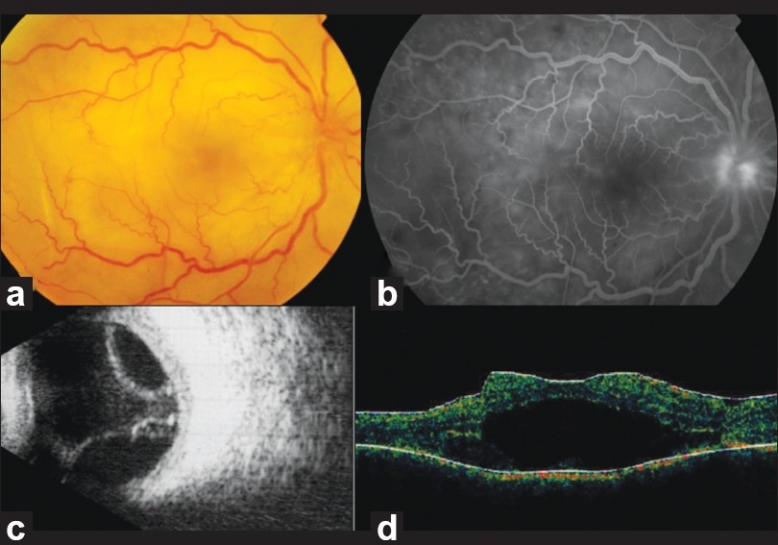

In the posterior segment, the extent of inflammation can vary. Patients may have vitritis, retinal vasculitis, choroiditis, and papillitis. The extent of inflammation may sometimes be represented by serous retinal detachment and optic nerve swelling in affected patients. Indirect ophthalmoscopy is helpful for following the course of the disease [Figure 2].1026 White-yellowish lesions at the choroidal are more common in the peripheral fundus of patients with SO (Dalen–Fuchs nodules) [Figures 3 and 4]. Dalen–Fuchs nodules were initially characterized in eyes with SO. However, other granulomatous inflammatory eye diseases may also present with Dalen–Fuchs nodules including Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease and sarcoidosis.

Clinical presentation of sympathetic ophthalmia after cyclophotocoagulation: (a) diffuse choroiditis with papillitis. (b) Late frame fluorescein angiogram demonstrating optic disc and subretinal hyperfluorescence in the posterior pole. (c) B-scan ultrasound shows exudative retinal detachment OD. (d) Optical coherence tomography OD demonstrates elevation of the retinal layers with subretinal hyporeflectivity corresponding with subretinal fluid

Sympathetic ophthalmia after trauma: (a) Posterior pole of the right sympathizing eye demonstrating choroidal atrophy. (b) Multiple small Dalen–Fuchs nodules can be seen throughout the fundus in this sympathizing eye. Cell infiltrates were present in the vitreous. (c) This case was complicated by cataract and refractory glaucoma. The patient was treated by cataract extraction and trabeculectomy with mitomycin C initially followed by an Ahmed valve implant. (d) Exciting phthisical left eye after trauma

Fundal white dots in the macular region accompanied by retinal vasculitis were observed in the right eye of a 33-year-old male, who underwent multiple intraocular surgeries in his left eye. The findings in the right eye were detected 4 weeks after the last surgery in the left eye (Reprinted with permission from BenErza D25)

The sequelae of inflammation noted in SO are quite variable, depending on the severity of the ocular inflammation and whether therapy has been initiated. Secondary glaucoma as well as cataract can be present. In addition, retinal and optic atrophy may occur in association with retinal detachment, subretinal fibrosis, and underlying choroidal atrophy.27 Choroidal neovascularization and phthisis bulbi are rare and are usually related to delayed diagnosis and inappropriate treatment.

BenErza documented various factors that contribute to the development of clinically apparent SO [Table 1].25

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of sympathetic ophthalmia is based on history and clinical examination. There are no specific laboratory studies to establish the diagnosis of SO; however, focused clinical testing can be used to rule out other disease entities with a similar clinical picture. Fluorescein angiography (FA) and indocyanine green video-angiography (ICG-V) are useful adjuncts in establishing the extent and severity of SO.

In the acute phase of SO, FA typically demonstrates multiple hyperfluorescent leakage sites at the RPE during the venous phase that persist into the late frames of the study [Figures 5 and 6]. There may be spreading of the dye from these areas and, in severe cases, pools of the exudates coalesce into large areas of exudative retinal detachment.10 The less common appearance of SO in FA is that of early hypofluorescent lesions and late staining similarly to that seen in acute multifocal posterior placoid pigment epitheliopathy.28 The status of the RPE overlying Dalen–Fuchs nodules or the integrity of the choriocapillaris is what determines the fluorescence of these lesions. Blockage of choroidal fluorescence may occur when an intact dome of RPE contains the cellular elements of the Dalen–Fuchs nodules. Gradual accumulation of fluorescein into Dalen–Fuchs nodules may produce focal hyperfluorescence [Figure 6b]. However, degeneration of the RPE overlying the Dalen–Fuchs nodule may allow fluorescein dye to permeate focally into the RPE and gradually accumulate in the subretinal space.29 Late staining of the optic nerve head is sometimes observed, even in the absence of clinical papillitis or optic nerve head swelling.

Fluorescein angiography of the acute phase of sympathetic ophthalmia showing multiple hyperfluorescent dots in the mid-periphery with some confluence anteriorly (Reprinted with permission from Damico FM et al.,26)

Sympathetic ophthalmia in the left eye after trauma to the right eye. (a) The color fundus photograph demonstrates optic disc edema and hypopigmented round 100-200 μ in size lesions in the posterior pole (Dalen–Fuchs nodules; white arrows). (b) Fluorescein angiogram shows that the lesions are hyper and hypofluorescent, and accompanied by choroidal folds inferotemporally. (c–f) Optical coherence tomography (horizontal scans) characterize the Dalen–Fuchs nodules as fusiform hypereflective lesions of the RPE (white arrows). Note the hyporeflective outer retina associated with optic disc edema

As the disease process predominantly involves the choroid, ICG-V may be a useful adjunct to fluorescein angiography both for diagnosis and in evaluating the response to treatment. ICG-V studies show multifocal hypofluorescent spots that became more prominent as the study progresses. These lesions are thought to be reflective of choroidal inflammatory cellular infiltration and choroidal edema.3031

Time domain optical coherence tomography has shown disorganization and thinning of the inner retina, and pronounced disintegration of the RPE and choriocapillaris.32 Fourier Domain OCT is also able to show choroidal and RPE thickening in SO patients [Figure 6c–f].

B-scan ultrasonography in SO demonstrates marked choroidal thickening and retinal detachment in some difficult cases.

HISTOPATHOLOGY

The basic finding in the histopathological analysis of eyes with SO is granulomatous inflammation throughout the uveal tissue, except for the choriocapillaris and retinal vessels [Figures 7–9]. On histopathologic inspection, the yellowish-white choroidal lesions seen clinically correspond to collections of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and de-pigmented RPE cells lying beneath Bruch's membrane. Retinal infiltrates have been reported in 18% of SO cases.34 Specifically variable degrees of retinal involvement, including perivasculitis, retinal detachment, and gliosis have been described. The inflammatory cells involved in SO are primarily lymphocytes, epithelioid cells, and multinucleated giant cells, all of which are components of classic granuloma. Occasionally, eosinophils, neutrophils, and plasma cells may be present.34–36

Enucleated specimen of a patient with a ruptured globe by penetrating ocular trauma, who developed sympathetic ophthalmia two weeks after the event. The cornea demonstrates a scar at the trauma site. Note exudative retinal detachment and choroidal thickening more prominent posteriorly (Reprinted with permission from Evans M33)

Photomicrograph shows Dalen–Fuchs nodule in a patient with sympathetic uveitis. Note, the collection of mononuclear cells and RPE cells beneath the RPE and Bruch's membrane (Reprinted with permission from Evans M33)

Sympathetic ophthalmia. The choroid is infiltrated by lymphocytes and macrophages separated by groups of multinucleated cells and epithelioid cells (Reprinted with permission from Evans M33)

Dalen–Fuchs nodules are found in approximately one-third of enucleated eyes thought to have SO [Figure 8].37 The fundal white dots are the ophthalmoscopic counterpart of the choroidal granulomata or Dalen–Fuchs nodules observed histologically. The localization of the Dalen–Fuchs nodules is first and foremost within the choroid, as can be seen in the gross specimen of eyes with SO. However, histologic sections and immunostaining demonstrate that Dalen–Fuchs nodules can be found within the choroid, under the RPE or under the neuroretina. Immunohistochemical identification of the cells in Dalen–Fuchs nodules demonstrated cells originated mostly from the reticuloendothelial system (histiocytes, lymphocytes, and de-pigmented epithelial cells). The cellular compositions of Dalen–Fuchs nodules in SO and in sarcoidosis are identical.3538–40 The RPE generally remains normal in appearance, but it may or may not be intact anterior to these nodules. Reynard et al,29 reported an interesting morphological variation of Dalen–Fuchs nodules in SO. They found three types of lesions at the level of the RPE.29 One type was a focal hyperplasia and aggregation of retinal pigment epithelial cells. The second type, classically referred to as Dalen–Fuchs nodules, consisted of epithelioid cells and lymphocytes covered by an intact dome of RPE. The third type of lesion was characterized by degeneration of the overlying RPE leading to disorganization of the Dalen–Fuchs nodules and possible release of their contents into subretinal space. The spectrum of morphological changes occurring at the level of the RPE is consistent with the Fuchs original hypothesis that Dalen–Fuchs nodules undergo on evolutionary sequence of development. Jennings et al,41 suggest that the clinical appearance of Dalen–Fuchs nodules appears to correlate with the severity of the disease.

ETIOLOGY

The etiology of SO is not clearly understood. Autoimmunity and cell-mediated immune mechanisms are considered to play a mediating role in the pathogenesis of SO. However, this concept is not a new one, having been proposed by Elschnig in 1910 with uveal pigment being considered a putative antigenic stimulus. Elschnig postulated that the injury to the exciting eye resulted in an absorption and dissemination of uveal pigment, which produced the hypersensitivity reaction in the injured eye. The continued absorption resulted in an allergic reaction in the sensitized tissue of the sympathizing eye. Current evidence suggests that choroidal melanocytes alone as an inciting target is considered insufficient to induce SO. The cell-mediated immunity observed in SO could be directed against some uveal antigen,42 a retinal antigen (such as Sag)37 or a surface antigen shared by photoreceptors, RPE, and choroidal melanocytes.35 To date, no circulating antibodies directed against intraocular tissue have been found. No organism has ever been consistently isolated from eyes with SO, and the disease has never been incited in animal models following injection of an infective agent. Nonetheless, through molecular mimicry of an endogenous ocular antigen, a bacterial antigen, rather than active proliferation of the organism, may be the inciting agent in the immune response.43

Albert et al,4 proposed a unified model to explain the pathogenesis of SO. They proposed that since the choroid has no lymphatics,4 the removal of intravitreal antigen by blood stream, or possibly, conveyance of suppression signals by intravitreal immunoreactive cells to bloodstream and spleen results in immunologic tolerance. In penetrating injuries followed by uveal prolapse, there is access of uveal tissue to the conjunctival lymphatics, resulting in a removal of the antigen or suppression signals to the regional lymph nodes. In the latter sites, there is a sensitizing reaction to the uveoretinal antigens, or some inhibiting signal. The antigenic load may affect the histopathologic picture. The findings of Rao et al,37 suggest that a high dose of antigen early in the course of the disease may induce a transitory antigen–antibody reaction. Furthermore, there is a key role for activated helper-T lymphocytes to affect and perpetuate the ultimate immunologic attack.35 This type of lymphocyte likely recognizes cell surface antigens shared by the membranes of photoreceptor and RPE cells. In the retina, the Müeller cells may profoundly suppress the proliferative response of primed T-helper lymphocytes to antigen present on conventional antigen-presenting cells, as well as their subsequent interleukin-2-dependent expansion. The damage inflicted by the T cells on the uvea is for the most part focal and slow, and is rarely accompanied by fulminant necrosis. Histiocytes and epithelioid cells also enter the immunoreactive sites adjacent to the uvea and become part of the Dalen–Fuchs nodules. In the same manner, the RPE cells proliferate and change to become incorporated in the nodules. In cases where T-cells are able to bypass the RPE and enter the retina, retinal inflammation and damage may ensue.4

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis of SO includes all diseases that can present as panuveitis. However, patient history will reveal previous penetrating ocular injury or intraocular surgery [Table 2]. Occasionally, it may be difficult to distinguish SO from VKH disease. However, patients with VKH have no history of surgery or trauma and VKH presents as bilateral granulomatous panuveitis with prominent choroidal involvement. Typically, patients with VKH have serous retinal detachment and optic nerve involvement, not seen in SO. In addition, VKH is also more prevalent in certain racial and ethnic groups, and they may have skin and hair changes, such as vitiligo, alopecia, or poliosis, or neurological symptoms such as tinnitus, headache, or mental status change. If it is necessary to differentiate from VKH, the cerebral spinal fluid of patients with VKH may reveal pleocytosis in 84% of cases. VKH and SO are autoimmune disorders targeting melanin-bearing cells. Both diseases are characterized by immunologic dysregulation. Al-Halafi et al,44 found a statistically significant association of systemic disorders and malignancy with VKH compared to SO. This finding suggests that the two disorders have different etiology with similar ocular and systemic manifestations.

Lymphoma, syphilis, tuberculosis, and sarcoidosis have to be ruled out as these diseases demonstrate multiple small foci of choroiditis with vitreal cells. If lymphoma is suspected, careful systemic workup, including neurological evaluation, should be performed. If necessary, a vitreous sample must be obtained for diagnostic purposes. Tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, and syphilis are usually accompanied by constitutional signs and symptoms of the underlying systemic disease. These features, combined with appropriate testing for tuberculosis (PPD skin testing and chest radiograph), sarcoidosis (serum angiotensin-converting enzyme and lysozyme, and chest radiograph), and syphilis (RPR and FTA-ABS) can distinguish these systemic infections from SO.

It is important to rule out potentially devastating fungal and bacterial infections, which may evolve rapidly from uveitis to severe endophthalmitis. Post-traumatic iridocyclitis may also cause an inflammatory reaction. However, neither infection nor iridocyclitis involves the fellow eye.

TREATMENT

The treatment of SO is primarily medical. The mainstay of treatment is systemic immunomodulatory therapy. Systemic corticosteroids are the first-line therapy for SO. They may be given topically, by sub-tenon or transseptal injection, and systemically. Oral prednisone is most frequently employed in the treatment of SO. Treatment is initiated with high dosage oral prednisone (1.0 to 2.0 mg/kg/day) and tapered slowly over 3 to 4 months. In severe cases, intravenous pulse steroid therapy can be employed (methylprednisolone 1.0 g/day for 3 days). Adjunctive topical corticosteroids and cycloplegics are used to prevent synechia formation from the anterior chamber reaction. The clinical criterion for response to therapy incorporates an appraisal of the inflammatory response, such as the degree of choroiditis and papillitis. If there is a significant decrease in inflammation, a slow taper of the oral corticosteroid may be initiated. The minimum dosing schedule required to control inflammation is at least a year in most cases. However, steroid use is associated with the development of cataracts and glaucoma. Regional injection of steroids in the peribulbar space can result in scarring of orbital tissue and glaucoma.

Steroid-sparing immunomodulation may be more advantageous in patients with SO. If patients are steroid-resistant or have intolerable side effects, cyclosporine can be used as a long-term immunomodulatory agent. Cyclosporine is initiated at a dose of 5 mg/kg/day and increased until the ocular inflammatory reaction is controlled. Once the disease is in remission for at least 3 months, a slow taper (0.5 mg/kg/day every 1–2 months) of cyclosporine can be initiated and progressively substituted by low doses of corticosteroid. Nussenblatt et al,45 reported successful use of cyclosporin A in conjunction with prednisone.

Other immunosuppressive agents including chlorambucil, cyclophosphamide, or azathioprine may also be utilized if the inflammatory reaction cannot be adequately controlled with corticosteroids or cyclosporine. Jennings and Tessler46 described favorable results with various combinations of cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, and chlorambucil with or without steroids. Mycophenolate has also been recommended for the treatment of refractory panuveitis or posterior uveitis unresponsive to high-dose maintenance steroids (>15 mg/day) or other immunosuppressive agents or where toxicity concerns exist.47 Dosage is 2 g orally and blood count monitoring is necessary. Tacrolimus has also been shown to be effective; however, renal dysfunction and glucose intolerance should be monitored.48 Given the more powerful nature and less favorable side-effect profile of these agents, collaborative management with experienced immunology specialists is advisable.

Atan et al,49 studied whether polymorphisms in the cytokine genes are important markers for disease severity and outcome in patients with SO. Their49 results show that cytokine gene polymorphisms are markers for the severity of disease in SO and were found to be associated with recurrence of previously stable disease and with the level of maintenance steroid treatment required to control inflammation.

Recently, Mahajan et al,50 proposed that fluocinolone acetonide implant provides inflammatory control and reduces the dependence on systemic immunosuppression in patients with SO.

PREVENTION

Surgery prior to disease onset appears to play an important role in the prevention of SO. In general, the time frame required for this approach is believed to be within 10 days to 2 weeks from the penetrating injury.14 The problem with this approach is that with current advanced surgical techniques, many eyes once considered nonviable may now have a fair prognosis. Therefore, current opinion sustains that SO is extremely rare and can be effectively treated in most cases. Recently, Savar et al,51 reported their experience with enucleation after open globe trauma at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary center. Among 660 open globe injuries, 55 had undergone enucleation, 11 primary, and 44 secondary cases were documented.51 The most common reason for secondary enucleation was a blind, painful eye.51 In their51 series only two patients (0.3%) developed SO and had maintained good vision in the sympathizing eye. Savar et al,51 used Bellan hypothetical calculations51 to find that between 908 (assuming a sympathetic ophthalmia rate of 3.1%) and 9999 (assuming a SO rate of 0.28%) prophylactic enucleations following open globe injury would need to be performed to prevent one case of legal blindness from SO. We recommend that primary anatomical reconstruction should be performed and that should be followed by discussion with the patient and family members regarding whether to retain or remove eye.

Controversy remains with respect to enucleation of the exciting eye after development of SO development for the management of this condition. Kilmartin et al,12 found that once SO develops, secondary enucleation of the exciting eye to reduce inflammation in the sympathizing eye does not necessarily lead to a better visual outcome or to a reduced need for medical therapy. Unfortunately, the time frame necessary to perform prophylactic secondary enucleation remains uncertain, as SO has been reported with secondary enucleation performed as early as five days following a penetrating ocular injury.16 In addition, in certain cases the exciting eye may become the better seeing eye after chronic or severe SO. However, the pre-existing lack of vision in previously injured eyes changes the context in which a subsequent penetrating ocular injury is managed. In this setting, repairing the injury in order to assess for visual potential is futile, and primary enucleation may offer the best prophylaxis against SO.165253 Although it would appear that evisceration after severe ocular trauma is a safe option with a very low risk of developing SO, it is known that SO may occur due to uveal tissue remaining behind in scleral emissary channels. We suggest the surgeons pay particular attention to the theoretically increased risk of SO after evisceration versus enucleation.

SUMMARY

Sympathetic ophthalmia is a rare and potentially visually devastating bilateral panuveitis, typically following surgery or non-surgical penetrating injury to one eye. High index of suspicion is vital to ensure early diagnosis and initiation of treatment, thereby allowing good final visual acuity in most patients. Diverse clinical presentations are possible in SO and any bilateral uveitis following vitreoretinal surgery should alert the surgeon to the possibility of SO.

Although there is no consensus regarding optimal treatment, most experts concur that SO requires prompt attention and treatment. Prompt and effective management with systemic immunosuppressive agents may allow control the disease and retention of good visual acuity in the remaining eye. Modern immunosuppressive therapy with systemic steroids and steroid-sparing agents such as cyclosporin A and azathioprine have improved the prognosis of SO. However, informed consent for vitreoretinal surgery (especially in re-operations) should now include the risk of SO (approximately 1 in 800).